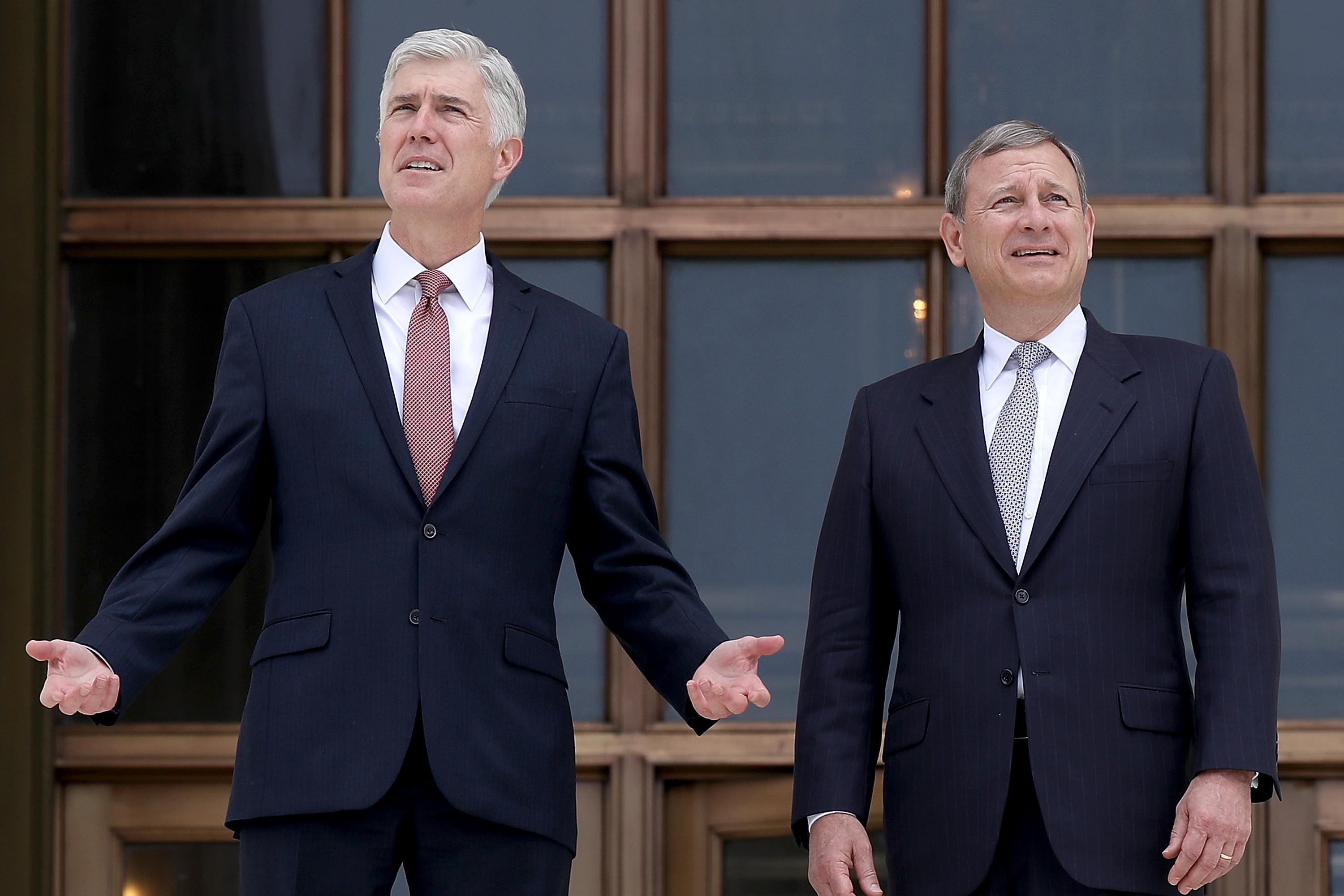

The Supreme Court issued a 5–4 decision Monday in Epic Systems v. Lewis allowing employers to deprive their workers of their right to sue collectively. Its ruling, written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, blasts a massive hole through post–New Deal labor law, hobbling employees’ ability to recover in court when their employers underpay them. It is difficult to overstate how devastating Epic Systems is to labor rights in America—and how far Gorsuch strays from federal law in order to implement his preferred economic policy.

Epic Systems revolves around a group of employees who sued their employers for “wage theft,” alleging that they had illegally underpaid them. Each of their individual claims is fairly small and probably not worth the cost of litigation. But taken together, their claims add up to a substantial sum, and so the employees filed a class action on behalf of themselves and others who were similarly wronged. Their employers fought their lawsuits, arguing that the Federal Arbitration Act blocked their claims because the workers had all been forced to sign contracts that waived their right to sue and instead shunted them into one-on-one arbitration. (The arbitration process strongly favors employers.)

This argument, however, conflicted with a decision by the National Labor Relations Board, the independent agency tasked with implementing federal labor law. In 2012, the NLRB held that the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, or the NLRA, nullifies arbitration clauses in cases like this. Its reasoning was simple. The Federal Arbitration Act declares arbitration agreements “valid, irrevocable, and enforceable,” except “upon such grounds as exist at law.” And 10 years after Congress passed the FAA, it passed the NLRA, a signature piece of New Deal legislation that guarantees workers “the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” (Emphasis mine.)

Quite sensibly, the NLRB found that lawsuits designed to collectively enforce workplace rights qualified as “concerted activities for the purpose of … mutual aid or protection.” It thus found that the FAA must yield to the NLRA when employees file class actions to protect their interests under federal law.

Now, however, the Supreme Court has overturned that interpretation of the law. Gorsuch, the self-proclaimed textualist, rests his conclusion largely on the “structure” of the NRLA. He insists that class actions do not qualify as “concerted activities” for workers’ “mutual aid” because the NRLA does not expressly mention them. Never mind that the plain text of the statute is designed to safeguard collective rights that Congress didn’t list in 1935 but that might arise down the road. Never mind that collective action—though the courts, if necessary—is precisely the kind of activity that the NLRA was explicitly meant to fortify. To Gorsuch, “concerted activities” include only activities “closely related to organization and collective bargaining, such as picketing.” This assertion is based not in the text of the law but in the justice’s own wishful thinking.

In one of the most furious dissents of her career, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg tore into the majority for insisting that it was not “substitut[ing] its preferred economic policies for those chosen by the people’s representatives.” She accused Gorsuch of returning the Supreme Court to the Lochner era, when the justices routinely struck down workers’ rights under a dubious theory of economic liberty. The “edict that employees with wage and hours claims may seek relief only one-by-one,” she wrote, “does not come from Congress.” Instead, it is “the result of take-it-or-leave-it labor contracts harking back to the type called ‘yellow dog,’ and of the readiness of this Court to enforce those unbargained-for agreements. The FAA demands no such suppression of the right of workers to take concerted action for their ‘mutual aid or protection.’ ”

Gorsuch’s opinion in Epic System will have an immediate impact on workers. It effectively legalizes low-level wage theft; Juno Turner, a partner at the workers’ rights firm Outten & Golden, told me that it “gives a free pass for companies to break the law,” because “employers can now cheat workers with little risk that employees will enforce their rights.” The decision was predictable—the Supreme Court’s conservatives have already eviscerated the right of consumers to file class actions—but it is still nothing less than catastrophic for workers across the country.

There is one glimmer of hope in the aftermath of Epic Systems: The decision will prove to be deeply unpopular, particularly among Democrats. Earlier this year, the progressive group Demand Justice polled likely Democratic voters in 11 states, including swing states like Michigan and North Carolina. It found that 68 percent of respondents believe the Supreme Court is more favorable to the rights of businesses than the rights of workers.

By any objective standard, that conclusion is surely correct. And Democrats’ overwhelming belief that SCOTUS is biased toward business interests raises the possibility that Democratic politicians may prioritize fixing the court’s errors in cases like Epic Systems. If the party retakes Congress, it could easily amend the FAA to undo SCOTUS’s damage and clarify that businesses cannot thwart class actions through mandatory arbitration agreements. Until that happens, though, the Supreme Court’s conservatives will continue to read the FAA’s penumbras and emanations to quash employees’ access to justice.