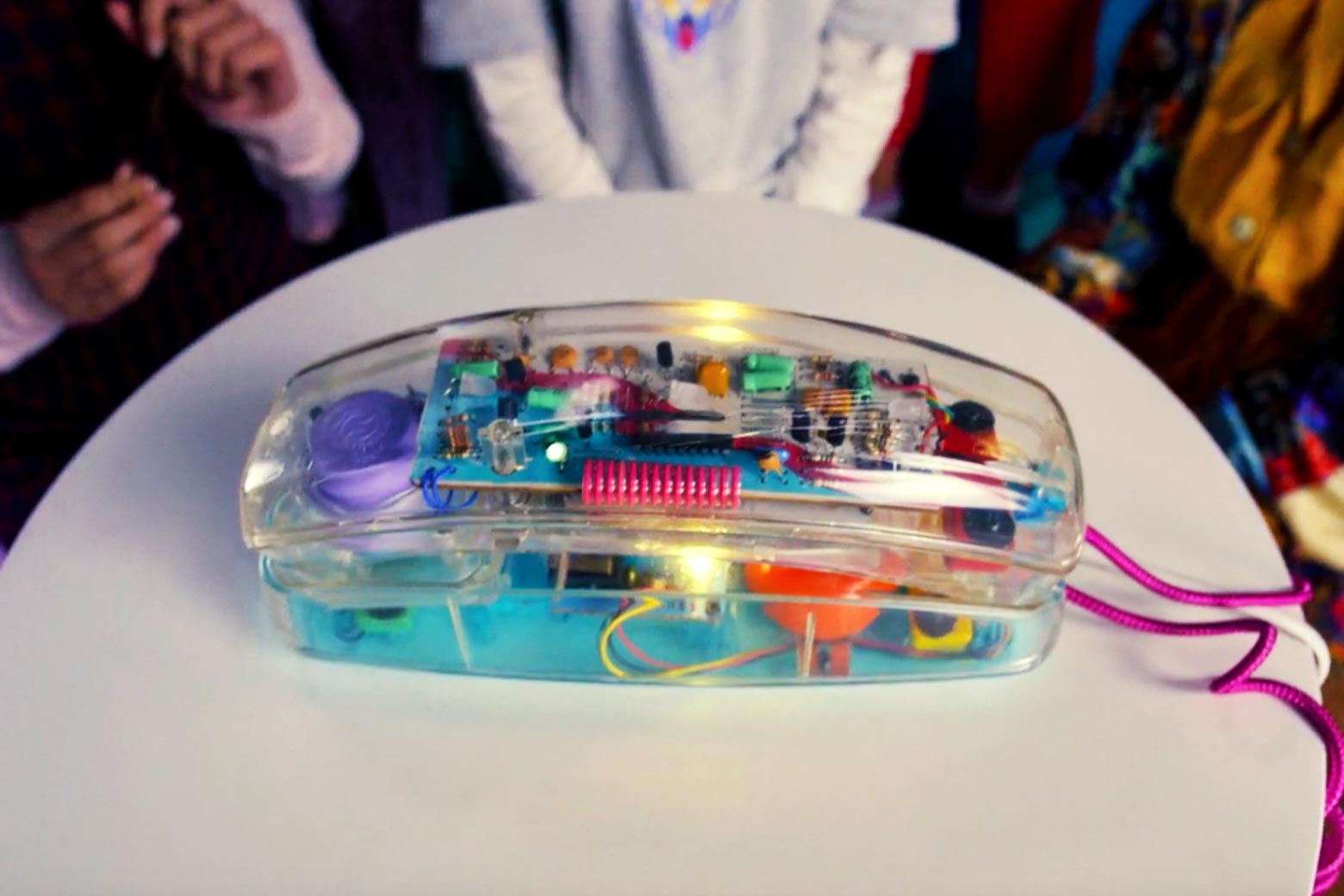

Of all the waves of nostalgia that Netflix’s Baby-Sitters Club reboot sent rippling through my regrettably millennial soul, none were stronger than what I felt when I laid eyes on one fateful prop: a certain very important telephone that features prominently on the new show. See-through with colorful parts inside it, it lights up when it rings, and it sits in the oft-seen bedroom of the club’s vice president, Claudia Kishi.

“Are you sure this thing actually works?” Kristy, the club’s president, asks Claudia in the first episode.

“The Etsy shop I bought it from said it’s fully operational,” Claudia answers with a shrug.

“Yeah, but it’s 25 years old,” Kristy shoots back.

“It’s iconic!”

Claudia is right: This isn’t just any phone. It was the phone, the one from Conair that seemingly every girl who grew up middle-class in the suburbs in the ‘80s or ‘90s wanted. This phone’s flamboyance marked it as something no respectable adult would buy and put in the living room; it was for teens only, a declaration of independence. Whether they remember it from Clarissa Explains It All or another TV show or the mall or a friend’s house, many people have a special place in their hearts for this hunk of plastic.

Among the girls who coveted the clear phone all those years ago was Rachel Shukert, who grew up to be the creator and showrunner of the Netflix BSC adaptation. “I knew people that had that phone—and I didn’t have the phone—but it was the coolest phone I’d ever seen,” Shukert told Slate. “When I pictured them all sitting in Claudia’s room, which I did constantly as a child, I would picture that phone being the one that rang. And so when I wrote the pilot, I was very specific in the stage directions about what kind of phone it was.” (To accompany a Los Angeles Times article that published a few days ago, Shukert was photographed holding one of the phones up to her ear, to match a photo right next to hers of none other than Ann M. Martin, author of the book series, also with one of the phones.)

The BSC books sort of revolve around phone calls. “One of the things about the Baby-Sitters Club is that they had to have their meetings at Claudia’s house because she was the only one of them who had her own personal phone line,” said Katie Parker, a 35-year-old who, with a friend, hosts her own podcast about ’90s TV. The members met at an appointed time, and parents called in to book them for babysitting jobs. This meant that the TV adaptation, which is set in the present, had an obvious problem that needed to be addressed, one Parker said she thought about when she saw the trailer: “How was that gonna work if the show takes place today where all of these girls probably have cell phones? Nobody really has landlines anymore even.”

Shukert said that when she was thinking about how to solve the phone issue, she had a lightning-bolt moment: She was a new mother, and so many of the online services that were supposed to make finding a sitter easier were instead making it more complicated. They required users to do things like pay for memberships, write profiles, and go back and forth endlessly with candidates. Hence the appeal of a club with regular meeting times and the guarantee that parents would be able to book a trustworthy sitter on the spot. A tad convenient, but it works.

“It’s a bigger problem than you would initially think, updating it, to figure out why they need to be gathering around that particular phone,” said Jack Shepherd, a 41-year-old who is the host of the podcast The Baby-Sitters Club Club and just so happens to have had the clear phone too. “It makes sense,” he said. “Once you go down the path of being like, ‘We have to figure out a way to make this phone central again,’ to my mind, that’s the only phone you could get.”

The new series is definitely doubling down on the landline. The clear phone featured heavily in a teaser Netflix released in May, complete with a “calling” pun. Watching it, Mary Celeste Kearney, a professor at the University of Notre Dame who has studied the way media portrayals of telephones have come to signify teenage girlhood, was struck by its treatment: “The camera focuses on it so much it’s like another character. It’s a big reveal, as we would call it in film and television studies.” Netflix is also touting a hotline it started to promote the show, which gives fans a real phone number to call and interact with.

When it came time to acquire one of the famous phones for the show, “it was hard to find one that really worked,” Shukert said. “I know they had to fiddle with it a little to get it to light up. It’s amazing to watch a whole team of prop experts and production designers and set dressers laboring over this piece-of-crap phone from 1995 that probably cost like $14 at the time.” (She said “piece of crap,” I trust, with love.)

For a transparent item, the clear phone’s origins as an object of fascination are somewhat illusive. Why did we all know about and remember this phone? It was pretty cool-looking, but still, it’s a phone—they don’t usually become cult objects. For answers to that question, I spoke to some former executives at Conair. They remembered the clear phone well. “I see it every once in a while pop up on a TV show, like, ‘Hey, that was my phone,’ ” said Anthony Solomita, a former Conair employee who was involved in developing the phone. “Or every once in a while I’ll get a message from a friend on Facebook, ‘Hey, I saw your phone on such and such a show.’ ”

If it’s surprising to you that Conair, which was known for its styling tools and appliances, would make a phone, it was to people then, too. The company entered the phone business in the ’80s: “You can imagine all the jokes we used to face,” said Solomita. “I remember the first electronics show when we introduced telephones, and all the buyers would come into the booth and they’d hold the phone and they’d be like, ‘Where does the air come out of?’ ” (More recently, Conair has been in the news for a former top executive’s association with Donald Trump.)

But it wasn’t just Conair that was just getting into phone business at the time. Up until then, AT&T, also known as Ma Bell, controlled the phone industry, meaning almost everyone either bought or rented their phones from AT&T, or had to pay extra fees if they didn’t. The company did not encourage much variety in style or color. But in 1982, a court ruling came down that ordered AT&T to break up. Barry Haber, who worked in Conair’s consumer electronics division and later became its CEO, told me, “In the phone business, you have to understand that after the phones were deregulated, the industry went from one company, AT&T, being our phone supplier, to two years later, there were over 300 companies supplying telephones.”

It was a gold rush. This explains why the ’80s gave us not just the clear phone, but also the football phone, the Garfield phone, and the hamburger phone. “That’s why there’s this proliferation of weird phones in the ’80s, because the government actually dismantled that monopoly,” said Matthew Bird, who teaches industrial design and its history at the Rhode Island School of Design.

After Conair had success with a line of neon phones called “High Energy” (which had themselves been inspired by a popular series of hair dryers), it was looking for more phone designs that would appeal to the company’s core customers: women. Haber said he was traveling when he came across a see-through phone in a larger, less sleek shape. Kristy had her great idea, and this was Haber’s: He thought back to the “High Energy” phones, which had been manufactured in a style called trimline, and envisioned a clear trimline phone with neon parts inside. (The company eventually produced phones with other, non-neon palettes too.)

The trimline was a phone shape that dated back to the ‘60s, when it was designed by the famed industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss. What looks like a fairly standard phone to us now was so innovative at the time—because it moved the dial to the phone’s handset, and it had a curved handset with a curved circuit board inside it—that it earned a place in the Museum of Modern Art. This added to the clear phone’s appeal: “It’s not just that it’s clear,” Bird, of RISD, said. “It’s also that it was taking a serious phone that was designed as, you know, an office phone, and it made it into a teenager phone. When you take something that was stuffy and make it fun, it shifts it.”

Bird said that clear versions of electronics like phones had already been around for a while, but they were had traditionally been one-offs, made of glass and designed to demonstrate the technology inside them for business purposes. But with the advent of clear plastic, which in the ’80s manufacturing had only recently mastered, something like a consumer clear plastic telephone would be feasible for the first time. Bird distinguished the clear phone from other translucent gadgets that came later, like the iMac or Nintendo 64: Those casings emphasized how futuristic the items were. But the clear phone had more of a retro appeal, as if to ask, Bird said, “Remember this thing called a phone and how it had, like, circuit boards inside, and isn’t that funny?”

Conair’s clear phone came out in 1989 or thereabouts (Haber wasn’t sure of the exact year), and it was a hit. “Once we got it placed on the shelf, the sell-through was fantastic,” Solomita said. Haber estimated that the company sold 2 or 3 million of them over a five-year period.

It ended up in almost as many bedrooms, but many of the people who owned and loved the clear phone were pretty fuzzy on where it came from. “For how big a part of my life that phone probably was, thinking back to how I got it, it was almost as if it just appeared in my room one day,” Shepherd, the BSC podcast host, said. “I don’t remember thinking of it at the time as being a thing that everyone had, like I don’t remember there being conversations like, ‘We all have to go get this phone,’ but it was ubiquitous.”

Shukert said she recalled seeing the clear phone advertised inside of Archie comics, as a prize one could earn by participating in Olympia Sales Club or something like it. In a YouTube video, one man said he remembered that the phone was sold at Spencer Gifts and was featured in a Radio Shack catalog. Ultimately, the phone’s ubiquity was a result of a very different retail environment than today’s. Rather than a whole internet of choice, people mainly chose among the products they saw at the store—and this phone was in a lot of stores.

“It was probably one of the most widely distributed telephones we ever had,” Solomita said.

In consumer electronics, as in many things, the more popular you are, the more you get knocked off: Before long, other companies, like Unisonic and Lonestar, started making copycat clear phones. Gretchen Stelter, 38, a writer in Portland, Oregon, told me that she had a slightly different version of the phone that was tinted pink and from the clothing brand Guess. This was also around the time that Swatch released a phone, which wasn’t a copy of the Conair one but shared a similarly quirky look.

Good design and blockbuster status notwithstanding, when I asked people who owned the phone why they loved it, their answers tended to be more personal. After all, these phones accompanied some of them through some very formative years.

“It was a really big deal when we all got phones in our room,” Stelter said. In addition to prank-calling boys, she said, “I would sit and talk on the phone with one of my friends in middle school, and we would not speak while we watched 90210 together, and then during the commercials we would talk.”

“I remember finding excuses to make phone calls on that phone,” said Amy Spitalnick, a 34-year-old who had the phone way back when. “Ironically, I probably did book babysitting gigs on that phone.”

It seems notable that kids who didn’t have the clear phone, like Shukert, in some cases remember it just as intensely as those who did. “One of the first things I think about when I think about that phone is class,” said Dorothy Santos, 41, a film and digital media Ph.D. student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, whose research interests include telephone technology. The phone wasn’t very expensive—sources remember it costing somewhere between $15 and $30—but kids have a way of latching onto things they think mark them as different. “I really wanted that phone. Never got it,” she said. “I grew up in an immigrant household [where] having my own phone line was just like, that’s just never happening.”

The clear phone obsession also occasionally crossed gender lines: “I remember at one point my friends and I set up this really awesome pillow fort in the basement,” said Max Hawkins, 29. “We had a TV in there, and snacks, a refrigerator, and this phone. It felt like it was an important part of that whole setup.” (Hawkins was so enamored with the phone that a couple of years ago, he found one on eBay and, mostly for fun, rigged it so his cell phone calls would go to it via Bluetooth.)

“Thinking back, I have a very vivid memory of it,” Shepherd said. “I could tell you exactly where it was in my room. Part of that is because there’s a lost art of calling people to talk for three hours after school.”

Me, I’m waiting to see if the new Baby-Sitters Club will inspire any Gen Z-ers to want something as archaic as a landline phone. To be honest, I’m tempted. Stelter is, too. She told me that discussing the phone got her wondering if her parents might still have hers somewhere: “I don’t even have a landline, but I work from home, so I was like, ‘I’d kinda like to have that on my desk.’ ”