Most of us forget names, dates or places from time to time. But Hilary Doxford never did. While the rest of us smile about our common inadequacy, she knew she was experiencing a genuine malfunction of her high-performance brain. “I did have a really good memory and didn’t need to write things down,” she says. “And I used to be able to multiply two four-digit numbers together almost instantaneously.” But one day, she started getting the sums wrong.

The doctors sent her away at first. So you can’t remember names or multiply 3,765 by 1,983 any more? Oh well, that’s middle age for you. But Doxford, who was then in her late 40s, knew differently. “My benchmark is myself,” she says. “Even now, when I tell people, everybody says: ‘I would never have known.’ What I’m doing is no different from what other people are experiencing. But when I compare it to how I used to be … I can’t multiply a two-digit number by a one-digit number. I can do it if I add them – like 27 times three. It’s my short-term memory – when you need to hang on to a number because you need to use it. That’s what’s gone.”

Doxford went to the GP because her partner, Peter, had asked her to marry him. She wanted to be sure she would not be sentencing Peter to looking after a woman whose brain was deteriorating. “My GP said: ‘It’s normal – off you go.’”

Three years later, then a married woman, she went back. “All the symptoms were getting worse,” she says. Doxford is the general manager of a medical research charity. “I forgot the surnames of some of my staff. I started finding it hard to concentrate and focus. Then I started avoiding taking responsibility for things unless I absolutely had to.”

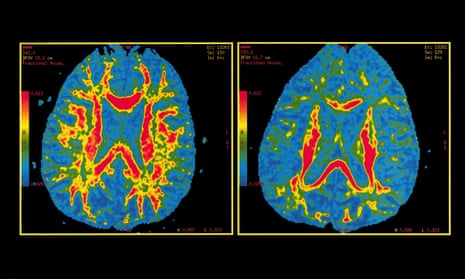

The GP said it was probably stress and sent her home again. But then she had a long, difficult business meeting with somebody, and when he greeted her three weeks later, she had no recollection of having met him before. This time she was sent for tests. She scored incredibly highly on the IQ part and incredibly poorly on memory, and was given an MRI scan. “The diagnosis was Alzheimer’s,” she says, matter-of-factly.

Dementia will take hold of one in three people who passes the age of 65, and costs the UK more than £26bn a year. This week the Office for National Statistics announced it is now the commonest cause of death in England and Wales, passing cancer and heart disease. People with dementia lose the ability to care for themselves and can become malnourished, while their immune system weakens. Infections such as pneumonia may be the actual agent of death, but dementia is the underlying cause.

It is a cruel disease, which takes away the person their families love and know, leaving a stranger who looks at them with confusion. And while there are are some drugs that will temporarily alleviate symptoms in some people, there is no cure. But dementia, of which Alzheimer’s is the commonest form, has finally begun to get the attention it deserves. In December 2013, the G8 countries, meeting in London, agreed to set an ambition to cure or come up with a significant treatment for Alzheimer’s by 2025. Last year David Cameron announced that the UK would set up a dedicated dementia research institute, with initial funding of £150m, and a further £100m from Alzheimer’s charities. Although the UK was already spending £300m on dementia research, Cameron believed it should be afforded the same level of resources as Aids and climate change. That was welcome news to campaigners, although, they say, the sum is still much less than that invested in cancer research (£590m in 2010).

Doxford, now 56, was glad to have a diagnosis. “On the one hand, it was a relief, because it explained all the problems I’d been having just doing normal stuff. On the other hand, ‘Oh shit’. The first question I asked the consultant was: ‘How long have I got being normal?’ He was implying that I only had two to three years, but then he said: ‘I do know somebody who is eight years down the line and she is pretty much OK.’” Others Doxford has met have since told her of people managing fine 10 to 15 years after diagnosis. For her, it has now been nine.

Initially she was put on Aricept (the brand name of donepezil), one of the few Alzheimer’s drugs currently available. These drugs help some people by delaying the worsening of symptoms, although they progress faster later on. But they do not work for everyone.

“It was pretty horrendous,” says Doxford. “I seemed to get all the side effects on the packet.” She began falling over. The worst was when she was tying up the boat that she and her husband kept. “We were in the marina and I had the rope in my hand. The next thing I knew, I was in the water.” They sold the boat, fearing for her safety. The consultant gave her another drug, but it was worse. “The first day I took it, I thought I was dying,” she says. She decided drugs were not for her.

There ought to be big money in Alzheimer’s drugs. It is more than a century since abnormal protein deposits in the brain were identified by the German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer as a likely cause of neurodegeneration. Over the past few decades, drug research has focused largely on attempts to clear the amyloid-beta peptides and tau proteins believed to cause these deposits, which gradually shut down the brain’s normal workings.

But there has been a very high failure rate, often at a late stage of development, when companies have spent a great deal of money – in some cases as much as $300m – on research and development. Dr Eric Karran, formerly the director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK and now leading the efforts of drug company Abbvie to find a cure, says that yes, it’s difficult, but too often in these failed trials, the preparatory work has not been thorough enough.

“Some people in the field would say that [the failure rate] has been a disaster,” he says. They suggest that the underlying concept, that Alzheimer’s is caused by amyloid plaque, may be wrong. “I would not subscribe to that view. There has been some sloppy science. We would not expect such trials to work anyway. In some cases there has been a very strong commercial push. In other cases, there has been a strong desire to get something into [human trials] because we have so little.”

Nobody would say research into Alzheimer’s is easy, says Dr Mike Hutton, chief scientific officer for neuroscientific drug discovery at the pharmaceutical company Lilly. “Amyloid accumulates in the brain for 10 to 15 years before you see clinical symptoms. There is a worry that we’re focusing on populations that are too far advanced.” Ideally, scientists must figure out who is most likely to get Alzheimer’s – then see if they can prevent healthy brains from developing it. But although there are some predictive tests available, it is hardly ethical to offer them to people when medical science cannot offer them treatment.

So the trials must be done in people with the earliest stages of dementia. And this year, for the first time, the results of two separate early trials have suggested that it may be possible to find drugs that might slow down the decay for people with mild dementia. Small wonder there have been wild headlines about a cure – a bit of good news is desperately wanted. One, Lilly’s solanezumab, a monoclonal antibody, failed in a large 2012 trial to slow the deterioration in most people with Alzheimer’s, but there was some improvement in those with the mildest form of the disease. Results from a new trial of more than 2,000 people with early-stage Alzheimer’s are eagerly anticipated, and due before the end of the year.

Another drug, Biogen’s aducanumab, made headlines in September. Trial results showed it almost completely cleared amyloid from the brains of a group of early Alzheimer’s patients, and that the expected deterioration slowed down significantly. The trial was small (166 people), and at the high doses that produced the best results, there were side effects such as headaches, but there was excited talk of “a game-changer”.

There has been such hype before, but David Reynolds, chief scientific officer of Alzheimer’s Research UK, says he is reasonably confident that the solanezumab results in December will also show an improvement in the symptoms of dementia, or at least a slowing of the decline. Sadly, there still seems little hope for those who already have moderate to severe dementia, beyond care and compassion.

In a nursing home in Hertfordshire, surrounded by trees and green spaces, James Gatesman, a former coroner’s officer and enthusiastic allotment gardener, spent the last years of his life in bed, his long legs angled to the wall, under a framed photograph of his Metropolitan police class at Hendon College. A yellow spot attached to the glass identified his own face in the picture.

You could still see the fine figure of a man that Gatesman had been – 6ft 2in with broad shoulders and a strong, handsome face. But he had ceased to speak, and could no longer move his own limbs. His daughter Deborah and his wife, Doreen, could only communicate with him through touch, or his occasional grunts, moans and howls.

“I always talk to him and treat him as if he understands us,” said Deborah, shortly before her father died. “I think of it as almost like locked-in syndrome – that he is in there. I worry about what we discuss in front of him.” When his wife paid for him to have music therapy, Gatesman responded to the Gilbert and Sullivan tunes he used to love with noises and movement of his hands. That confirmed Deborah’s belief that he was more aware than he seemed.

Gatesman was diagnosed in 2003, but Doreen recalls odd behaviour on a holiday in Australia in 1996, when he wandered away from their group and nobody knew where he was. In later years, his behaviour became unpredictable, and he refused to go to a doctor. “That was probably the worst time,” she said. “Where do you go for help?”

Eventually Gatesman had to see a GP because of an ear infection, and ended up in the memory clinic. He had a brain scan and was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. The progression was slow but inexorable. He was on Aricept for a year, but that was stopped when he was sent to a residential assessment centre – a care home where people with dementia spend some weeks or months while their condition and needs are determined. Instead, he was put on the drugs that are too often used to control the sometimes bizarre and agitated behaviour of dementia patients – antipsychotics. “He was throwing chairs around and he did pull a handrail off the wall,” Doreen says. When they visited him, he was no longer walking, but sitting in a reclining chair. “He was a bit of a dribbling mess,” said Deborah. “The antipsychotics were turning him into a zombie.” By the time he was moved to the long-term home in Hertfordshire, he was underweight. Doreen insisted the antipsychotics were stopped, and he regained not just his weight, but his spirit. Then “they had quite a lively character on their hands. He would run off down the corridors,” said Deborah. Or he would speak to the Polish nurses in the Flemish and German he had learned while in the RAF, in the war.

The Alzheimer’s Society has campaigned to reduce the use of antipsychotics – often referred to as the “chemical cosh” – in care homes. Dr Doug Brown, the organisation’s research director, says prescriptions have markedly reduced as a result, though “we wouldn’t say the problem has gone away. We still need to keep an eye on it”. The Society has piloted staff training in more than 100 care homes for “person-centred care”, which appears to cut the use of drugs dramatically. It involves taking the trouble to understand the triggers for an individual’s distress – such as the man who gathered all his furniture in the centre of his room every day and became upset when staff put it back. He was a decorator. Given a brush and a bucket of water, he spent contented hours thinking he was painting the walls.

The overuse of antipsychotics is one outcome of the past neglect of dementia, and further evidence of the real need for a drug that will do more than just quieten patients down – one that will slow the progress of a devastating disease and eventually, hopefully, cure it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion