Watch above: The number of so-called ‘doorings’ in Toronto is on the rise – but the number of charges aren’t. Mark McAllister reports.

Of the 1,308 Toronto cyclists hit by opening car doors between 2005 and 2013, most were hurt but only one was killed: A 57-year-old man biking east on Eglinton Avenue West on a May afternoon in 2008 when a 43-year-old woman opened her car door and sent the man flying into traffic, where he was hit by a truck. He died in hospital.

The woman was charged with “Open Vehicle Door Improperly” – the same charge applied, in theory, to any driver careless or callous or harried or busy enough to open a car door on a cyclist.

There have been more dooring incidents every year for the past seven.

But police are laying fewer charges for every dooring incident annually, Global News analysis has revealed.

We obtained records of every dooring incident and every charge laid between 2005 and 2013. The map of these “door prizes” is telling: Streets with the most incidents are narrow and busy and boast a treacherous combination of streetcar tracks and streetside parking.

College Street had more than any other stretch of road, with 73 incidents between 2005 and 2013.

“Have you ever ridden alongside parked cars near streetcar tracks?” asks Daniel Egan, the city’s head of cycling infrastructure.

“It’s a challenging issue for cyclists, because the only safe place to be is the middle of the centre lane, in the middle of the streetcar tracks. If you’re riding outside the streetcar tracks between the parked car and the streetcar tracks, you’re right in the dooring zone.”

Interactive: Explore our map of Toronto’s dooring incidents. Click a bubble for details. Enter a location in box to search. Double-click to zoom; click and drag to move around.

But the city has no plans to fix that.

“Politically it’s pretty tough to remove parking in any commercial area. You’re not going to narrow the sidewalks, you’re not going to move the buildings, and the streetcars aren’t going anywhere. ”

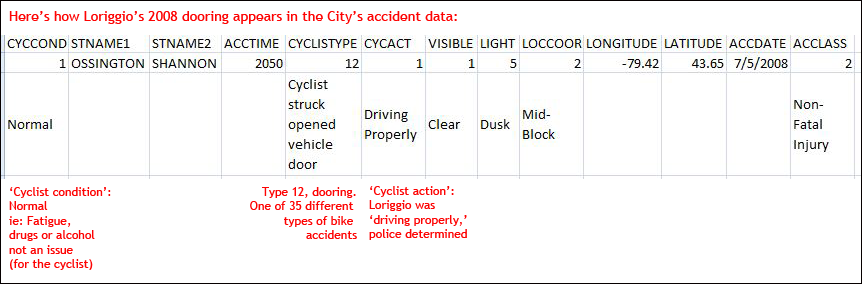

Paola Loriggio’s familiar with that “dooring zone.”

Biking homewards around 8 p.m. a July evening in 2008, Loriggio was on Ossington Avenue just south of College Street – slowing down on a slight uphill – when she noticed the lone parked car. Its driver was reaching for something while opening his door.

She had a split second to realize she was in trouble.

“Next thing I remember, I was in the ambulance.”

She remembers nothing of the impact itself. But the long crack along her helmet indicates just how hard she hit her head.

Loriggio got a concussion when she fell. But it took hours in pain at Toronto Western Hospital before medical staff realized her collarbone was broken.

That meant six weeks with her right arm in a sling, waiting for the bone to heal – and six weeks getting help with the most basic tasks. (Have you ever tried to make a ponytail one-handed? “It’s just impossible.”)

“At first, it was incredibly, incredibly painful. Afterward it just got to be extreme discomfort,” she said.

“You can never be comfortable when you have a broken collarbone.”

One thing she didn’t have to worry about was the charge against the driver: There were plenty of witnesses, people enjoying the summer night from their porches, who called 911 after the crash (and locked her crumpled bike to their fence afterward).

Loriggio filled out a police report while waiting in the emergency room.

“So many people had seen it, and, really, there was nothing else on the street – it was dead,” she said. “There were no other cars, there was no traffic. It was basically me going up a hill and this dude in a car.”

Since 2005, on average, about 120 Toronto drivers a year have faced a dooring charge, according to statistics provided to Global by the Ministry of the Attorney General.

But the ratio between charges and incidents is widening. As recently as 2008, recorded doorings and dooring charges were at almost a 1:1 ratio; by 2012, that number had fallen to 73%.

“One of the determining factors would be whether the witness* would attend court, or the cyclist,” said Toronto Police Sgt. Shane Stevenson. “There has to be someone there to describe the incident and describe what happened.”

It’s ultimately up to an individual officer to decide whether to lay a charge. Stevenson said they take into account all the evidence there, but wouldn’t say why police are laying fewer of them when it comes to dooring.

But Loriggio isn’t sure a fine, even a steeper one, will prevent future incidents.

“The problem is that people just don’t think about it. It’s not a calculated risk, it’s not like somebody who runs a red light and knows that it’s wrong but does it anyway because they know they won’t get caught. This is just people being careless and not thinking about it,” she said.

“I honestly don’t know. I mean, how hard is it to just look before opening your door?”

With files from Mark McAllister and Anna Mehler Paperny

Do you have a door-prize horror story? We want to hear from you.

*This word was originally ‘victim’ due to a transcription error.

Update, August 1: Download our dooring data

You can download a copy of our dooring database here. A guide to the numeric codes used in the data is here. (Control-S to download.)

Comments