In a Year, Child-Protective Services Checked Up on 3.2 Million Children

2.5 million of those kids were declared 'non-victims.' Another 686,000 were 'abused' or 'neglected.' And an estimated 1,640 kids died as a result.

The stories of Debra Harrell, the working mother who was arrested for letting her 9-year-old spend summer days alone at a park crowded with families; the widow who left four kids home alone for a few hours, only to have them taken by the state; and Kim Brooks, whose nightmare began when she left her kid in the car while running a quick errand, have all sparked sympathetic, insightful commentary at a number of national publications, along with lots of reader email. A number of correspondents granted that the families in these anecdotes were subject to overzealous responses, but guessed that their experiences are anomalous. Others felt that the larger problem is the state failing to remove children from legitimately dangerous situations that lead to grave injuries or even death.

Every year, the Department of Health and Human Services published statistics on the work of child protective service agencies in all 50 states, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico. The most up to date report available is Child Maltreatment 2012. It includes lots of useful context for the conversation that's now unfolding, including the baseline federal definition of child abuse or neglect:

Any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation; or an act or failure to act, which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.

States can build on that definition.

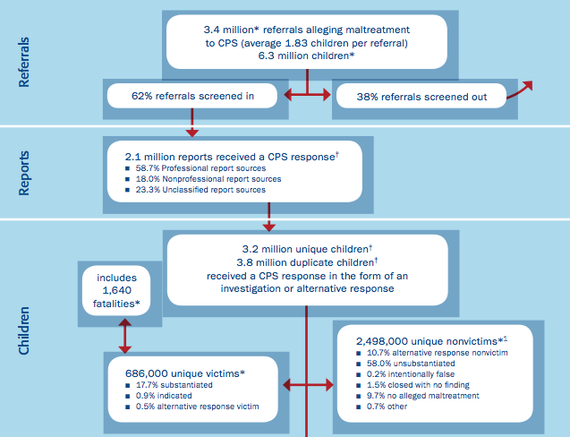

One statistic that stood out in the report: since 2008, the number of referrals to child protective service agencies (hereafter CPS) has increased by 8.3 percent, even as overall rates of actual child victimization declined by 3.3 percent during the same period. There is no system that can totally avoid putting parents who don't deserve it through investigations, despite the fact that even the best moms and dads would regard the ordeal as nightmarish. Over time, however, the number of undeserving parents so burdened seems to be increasing–and the number is large (note that "screened out" referrals are the ones deemed not even worth investigating):

Some of the families among the 2,498,000 referrals found to be non-victims were presumably guilty of abuse that CPS missed; others perhaps benefitted from CPS contact. (812,000 received "post-response services," some of which were presumably salutary.) Even excluding them, a lot of families went through a traumatic, frightening, intrusive experience before being cleared of unlawful abuse or neglect. And, of course, many of the 686,000 "unique victims" of abuse were in dire need of intervention, and thanks to good work by CPS, they're better off now. This report doesn't allow us to draw all the conclusions that would be useful about the relative incidences of these outcomes, though I'll get closer in future posts.

How Children Are Victimized

Reports of child abuse that make the nightly news might lead a casual observer to believe that CPS most frequently intervenes in the lives of families to stop people who beat or sexually abuse children in their care, or to prevent other horrific abuses.

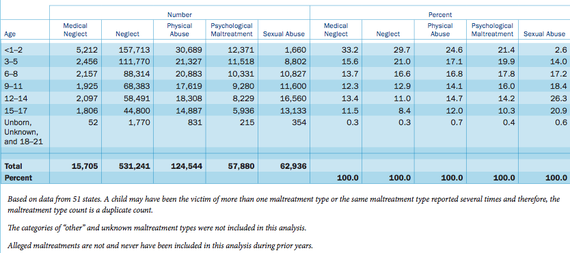

It is not so. In 2012, 686,000 children were deemed victims. In more than 80 percent of cases one or both parents were the perpetrators. Among the victimized children, 18 percent were physically abused, 9 percent were sexually abused, and 8.5 percent were psychologically maltreated. The vast majority, 78.3 percent of victims, suffered mere "neglect" without physical, sexual, or psychological abuse. The degree and harmfulness of neglect can vary tremendously, but in many cases would seem to lend itself to interventions short of taking the child and charging the parent–an approach that is only attempted in some states–especially given how many neglect cases are due largely to poverty.

An estimated 1,640 children died in 2012 as a result of abuse or neglect, mostly at the hands of parents. "Some children who died from abuse and neglect were already known to CPS agencies," the report states. "In 30 reporting states, 8.5 percent of child fatalities involved families who had received family preservation services in the past 5 years. In 35 reporting states, 2.2 percent of child fatalities involved children who had been in foster care and were reunited with their families in the past 5 years."

The Ages of Victims

Basically, the younger kids are the more likely they are to be abused, save for the category of sexual abuse:

Boys and girls were abused at similar rates.

Who Reports Parents to CPS

How Many Cases Involve Foster Care?

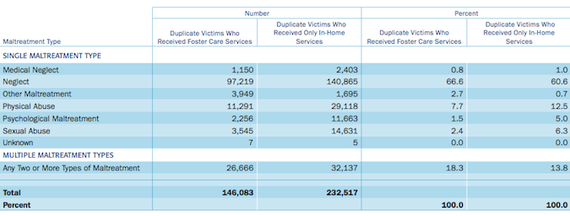

The numbers are a bit less certain here. The following table incorporates data from 46 states:

Most states also report "court actions," which may include "legal action taken by the CPS agency or the courts on behalf of the child, including authorization to place a child in foster care and applying for temporary custody, protective custody, dependency, or termination of parental rights. In other words, these include children who were removed, as well as other children who may have had petitions while remaining at home. Based on 47 reporting states, 21.4 percent of victims had court actions."

What's Missing?

There is much more data in the full report than I can include here. One data point I couldn't find, in the report or elsewhere: the number of children taken from parents, even temporarily, only to be returned with no finding of unlawful behavior.

Professor Paul Chill of the University of Connecticut School of Law explained the stakes in a 2004 scholarly article:

On an average day, police officers and child-welfare caseworkers throughout the UnitedStates remove more than seven hundred children from the custody of their parents to protect them from alleged abuse or neglect. These children are typically seized without warning from their homes or schools, subjected to intrusive interrogations, medical examinations and/or strip searches, and forced to live in foster homes or group residences while the legal system sorts out their future...Removals can be terrifying experiences for children and families. Often they occur at night. Parents have little or no time to prepare children for separation. The officials conducting the removal, as well as the adults supervising the placement, are usually complete strangers to the child. Children are thrust into alien environs, separated from parents, siblings and all else familiar, with little if any idea of why they have been taken there. Such experiences may not only cause “grief, terror and feelings of abandonment” but may “compromise” a child’s very “capacity to form secure attachments” and lead to other serious problems. The trauma may be magnified when the child is actually suffering abuse or neglect in the home, and in any event it is increased when reunification with loved ones does not occur quickly.