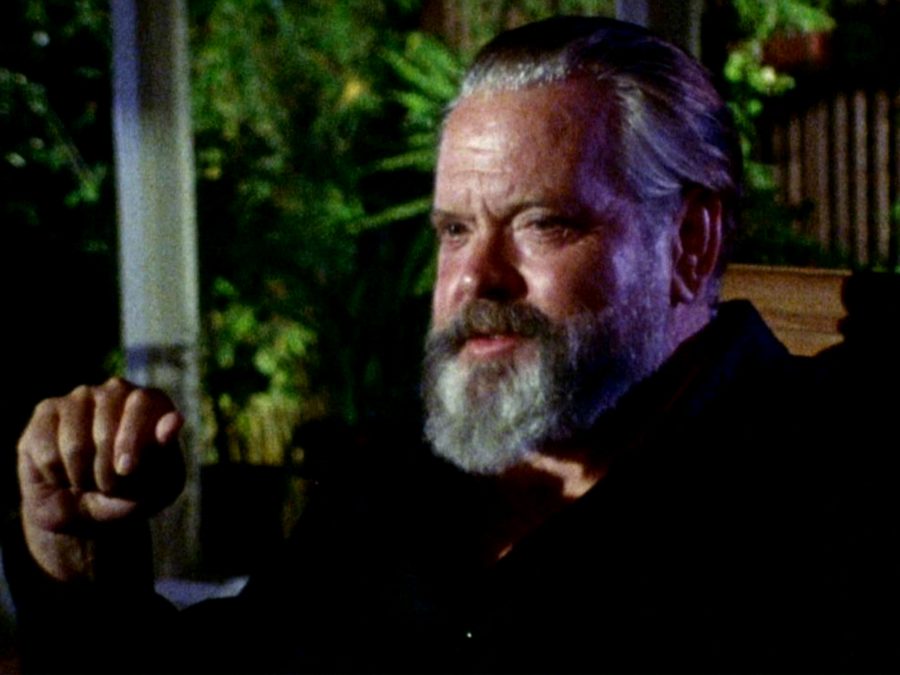

Orson Welles was a man measured by his cinema. He was so inextricably linked to the constant struggle of making films that it can be hard to differentiate between his life and his work. Welles had a multitude of talents which far outstretched that of his peers and for which he earned much of his income in order to live and make his own projects. With a background in theatre and radio, a turbulent relationship with Hollywood studios, a rekindled appreciation in Europe and a wealth of half finished projects in his wake, the director is the quintessential cinematic enigma.

This year sees a number of anniversaries of Welles’ films, from his debut satire to one of his last fully realised projects. His work reveals a great deal about where the filmmaker was in his life at any given moment, personally and creatively, even if the ultimate truth of the man is too complicated to ever be fully conveyed. Like their creator, these films combine sleight-of-hand illusions with an underlying truth, making them both enigmatic and earnest. Rather like Mr Akardin of Confidential Report, Welles had many, many masks and, seemingly, a film to go with each one.

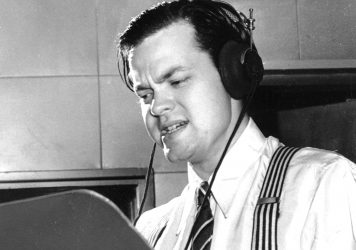

Welles’ public stature rose in the 1930s, not least because of the success of his and John Houseman’s radio and theatre company, The Mercury Theatre. This is as well as starring in the popular radio show, ‘The March of Time’, later satirised in his RKO debut, Citizen Kane. Touring widely with The Mercury Theatre in 1937 and moving the company to radio in 1938, a storm was caused by their production of HG Wells’ ‘War of the Worlds’ which is still widely known today for convincing many Americans of an impending Martian attack.

In Welles’ feature film debut, made that same year, we can see something far lighter: his admiration for the silent film era and its visual quirks. Too Much Johnson was not in fact released and was designed to be incorporated into a Mercury Theatre production. It never saw the light of day with the theatre venue lacking the projection facilities at the time. The film was eventually lost, said to have burned in a fire at Welles’ house in the 1970s. However, a print was recently discovered in Italy and restored. Its loose and mischievous feel highlights Welles’ persona perfectly; of course this is a man who would trick America into believing it was being invaded by Martians.

By the end of the 1940s, Welles had a range of projects under his belt as both actor and director though most were fraught with problems. Far from the freedom that he had had with Citizen Kane, Welles had found his creative liberty taken away as his relationship with Hollywood soured. Yet the decade ends with his ambitious first feature-length Shakespeare adaptation in Macbeth. Having already caused controversy in 1936 with his all-black Haitian version of the play at the Federal Theatre in Harlem, Welles would use the play to further his experiments with lighting and dubbing. Such experiments were, however, too much for take for critics at the time, especially in America and Britain where the film bombed at the box office.

Welles is clearly shaken at this point. He withdrew Macbeth from Cannes, worried by the presence of Laurence Olivier’s adaptation of Hamlet made that same year. Ironically, Olivier himself had avoided adapting Macbeth due to Welles’ project. After more disputes with the production company who were determined to hold the film back, fearing negative reviews and unhappy with its Scottish accents, Welles vaulted to Europe for a number of projects, returning briefly to make further cuts and to toe Macbeth’s production line. Macbeth seems an apt summation for Welles’ life in the 1940s; still battling on in spite of increasing creative adversity.

The 1950s is the decade when Welles really did lose control, with an almost constant struggle to either make or retain his vision. The decade opened with his adaptation of ‘Othello’ though it was a troubled shoot which stopped several times when the funding ran out. The film, however, won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1950. With equally troubled projects such as Confidential Report, the decade seems to have marked the end of his relationship with Hollywood, culminating with the noir classic, Touch of Evil.

The film follows the border police of a fictional Mexican town, embroiled in drugs, corruption and murder. Like many of Welles’ projects from this period, however, the production history is incredibly complicated, with a stream of endless cuts, memos and reshoots. The shooting of the film seems to have gone well with less of the interference that had plagued earlier projects, possibly due to Welles’ penchant for filming at night in order to avoid roaming producers. However, fearing the picture was too convoluted, Touch of Evil was heavily edited after Welles had finished his cut.

Though not entirely unhappy with all of the cuts – Welles was noted for liking the film’s new darker atmosphere – it is epitome of the director’s mistreatment by Hollywood. In spite of a number of extra scenes he didn’t shoot and a host of changes applied to his famously extended opening scene, Touch of Evil does represents Welles’ 1950s perfectly; dark, out of his hands and ever changing, yet still brilliant underneath.

Welles had found himself firmly in Europe by the end of the 1960s. His projects were funded by and filmed in a variety of countries and he had even moved once again back to television. Though his Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen) adaptation, The Immortal Story, would eventually find a theatrical release, it was designed initially to be part of a wider project for French television. It was filmed in 1966 and soon there were plans for further Dinesen adaptations. Welles once again called on the talents of Jeanne Moreau who had starred in his two main features of the decade, The Trial and Falstaff: Chimes at Midnight. He even opted to film the majority of The Immortal Story outside of his own house near Madrid.

Another of the failed Dinesen adaptations designed for the anthology, The Heroine, was set to star Welles’ last lover, Oja Kodar. Welles had met Kodar (then Olga Palinkaš) during the filming of The Trial and had begun an affair that was to last until the end of his life. She is perhaps better known for her prominent role in F for Fake but later starred in numerous short projects including yet another Dinesen adaptation by Welles in 1982 called The Dreamers.

Towards the end of Welles’ life, he ventured into a range of acting work, advertising work, television appearances and other smaller projects. In 1978’s Filming Othello, we see Welles working with a minimal budget and documenting himself, albeit in a less stylish fashion than seen in F for Fake. Filming Othello is largely a talking head documentary about the troubled filming of his Shakespeare adaptation. Though the footage is mostly interview and archive images from Othello, it has been suggested that Welles went and shot new footage in Venice to connect up his documentary though this has since been lost.

Filming Othello sits alongside a similar documentary, Filming The Trial, made a few years later. The scarcity of budget is all too clear here as the film consists solely of a question and answer session filmed at the University of Southern California. What is most interesting about these films, and Welles in general at this point, is that he is now willing to look back properly; something that seems only to have occurred previously when returning to projects that faltered or were unrealised.

Perhaps in these final, lo-fi projects, we can see a sense of contentment, Welles finally accepting his vast achievements whilst spurred on to fight for those projects still struggling to find their way out of the dream factory.

Published 11 Jul 2018

A passible Welles hagiography which offers very little that you won’t easily find in an Encyclopedia.

The Lady from Shanghai is a prime example of the legendary filmmaker’s complicated genius.

By Chris Owen

His withering letter to studio bosses is a filmmaking bible for our times.