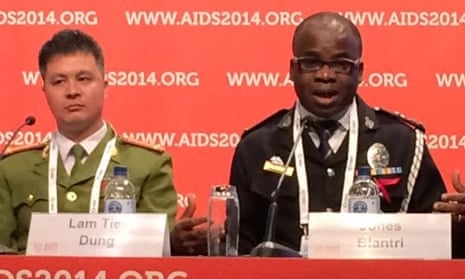

The chief superintendent of the anti-narcotics department of the Ghanaian police force, Jones Blantari, carries some special ammunition on his weapons holster – a bag full of condoms.

It’s a bold move, when the condom carries such negative religious and moral connotations among people in his country, making preventing the spread of infectious diseases – particularly HIV – difficult.

Criminalisation of key populations affected by HIV, such as sex workers, drug users and gay men, has driven those communities underground.

Which is why Blantari and his bag of condoms are leading a change in the way law enforcement is carried out. He and officers in other countries plagued by the Aids epidemic are deliberately choosing not to enforce certain laws that further stigmatise at-risk communities, forcing them away from treatment.

“Here in Ghana, if you use a condom, it is a sign that you are immoral,” Blantari said.

“I am a Catholic and in my faith people frown on the use of condoms. But I always tell people; what is better? Use a condom, protect yourself and others, and go to confession on Sunday if you are worried about it.

“Or don’t use protection, contract HIV, and the consequences of your actions will always be with you no matter how much you confess to God.

“Removing the religious perception that carrying a condom is immoral is difficult, but once people realise that you are talking a lot of sense, they start to listen to you.”

It was difficult for people to buy condoms in convenience stores or pharmacies, Blantari said.

“So it’s up to us as police to provide them and to demystify them,” he said. “If police feel comfortable with the condom and don’t attach moral behaviour to them, we are showing people condom use is normal.”

A new Open Society Foundations report, launched at the Aids 2014 symposium in Melbourne on Monday, has revealed how police, sex workers and drug users are working together to stop the spread of infectious diseases, particularly HIV.

“In countries from Russia to Zimbabwe, sex workers note that police use condoms or condom wrappers as evidence of prostitution, and that fear of police violence makes them reluctant to seek health and social services,” writes the UN Secretary General’s special envoy on HIV/Aids in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Michel Kazatchkine, in the report.

In Ukraine, for example, fear of police is the biggest factor associated with needle sharing among people who use drugs, the report says.

In Russia, Burma and Vietnam, police harass and arrest drug users who try to obtain health information and sterile syringes from pharmacies. In China, police have detained outreach workers at needle exchange sites and arrested people attempting to access clean syringes.

And there are still 76 countries which criminalise same-sex relationships.

“While public health experts describe sex workers and people who use drugs as ‘hard to reach’ populations, law enforcement has little trouble finding them,” the report says.

But the report also shows public-health centred law enforcement can curb the risk of HIV infections among drug users and sex workers in particular.

“We used to think of these people as our targets,” said Lieutenant Colonel Lam Tien Dung of the People’s Police Academy in Vietnam, at the Aids 2014 conference.

“But now we see them as our partners.”

The report comes as almost 10,000 current and former law enforcement officials from more than 35 countries have signed the Law Enforcement and HIV Network’s statement of support for harm reduction practices to control HIV among vulnerable populations.

The Network’s Prof. Nick Crofts said the biggest determinant of HIV risk in many countries was the police. And police often found it difficult to get involved in policy issues, risking disciplinary action if they spoke out.

“For anyone on the street, for marginalised communities, for those who are at increased risk of HIV, it is the police behaviour that determines that risk,” Crofts said.

“The fact is that we as an Aids community have ignored the opportunity to cooperate with the police force on the HIV response for too long.

“We’ve been documenting the bad impact police behaviour has on HIV risk and transmission, but far less work has been done on how to change those behaviours and bring police onside.

“It means we’ve been neglecting a critical part of the HIV response for 30 years.”

His organisation brings together police forces who are driving change in the way they treat sex workers, drug users and gay people. He said many police officers in developing countries had been rejecting their countries’ laws and refusing to criminalise people for their sexual or drug behaviour for years.

“What we’re doing is piggy-backing on processes of police reform going on around the world and bringing those police forces together, so we can show them they are not alone,” Crofts said.

“In this way they are not putting themselves so much in the firing line, because they can point to a whole network of other police officers doing similar work.”

He described officers such as Lam Tien Dung and Blantari, who attended Aids 2014 in their full police uniform, as “brave”.

“Turning up at an Aids conference in a police uniform – I would be more scared of the Aids community than I would be working in my own sector,” Crofts said. “If you are a sex worker, an HIV/Aids activist, a drug-users’ advocate, who has seen your friends and family brutalised by police, then you don’t feel good about police authorities.

“And you don’t want to see them at your conference.”

The former chief of the Seattle Police Department in the US, Jim Pugel, said police there were recognising politicians were too slow to change the law, and so police were working creatively until policy could officially catch up.

“Technically, police officers are involved in ignoring the letter of law which says you have to arrest people who have drugs.

“We recognise what the law is, but until it is changed the people on the ground, the police, say it’s not working, it’s causing harm, and increasing the transmission of HIV and other diseases.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion