How the Moon Became a Real Place

Once humans stepped on, smelled, and tasted the lunar surface—our relationship with it changed forever.

On a clear night and with the right telescope, if you know just where to look, you will find the cup-shaped crater called Draper. It's pocked into a vast plain of volcanic moon rock that humans once believed, from afar, was a lunar ocean. The mile-deep Draper aperture was named for physicist and astrophotography pioneer Henry Draper, the man credited with taking the first photograph of the moon through a telescope in the mid-1800s.

Those first photographs were as stunning as they were anticlimactic. For a celestial body that was thought to host bizarre extraterrestrial life, it looked, from afar, like something rather ordinary. "In truth, a common photograph of the moon does bear a striking resemblance to a peeled orange," wrote The County newspaper of Missouri in 1881. And yet moon photography was instantly popular—and people began collecting the images the way they sought out photos of popular actresses, newspapers reported.

In Draper's time, the moon was still more parts imagination than it was real. Though many dreamed of visiting it, such a journey was—and would be for the foreseeable future—the stuff of science fiction. Scientists debated the shape of the moon (egg-like, probably, they theorized in the 1870s). They argued over what sorts of animals might live there (big ones, many assumed). And they marveled at the gargantuan volcanoes spotted on its surface in the 1890s.

In popular imagination, the moon vivid, expansive, and fantastic. There was talk of winged creatures, moon elephants, scalding heat, and deep oceans. Newspapers were filled with stories—fictional, scientific, and artistic. In 1902, The San Francisco Call had an actual man act out the various faces of the man in the moon:

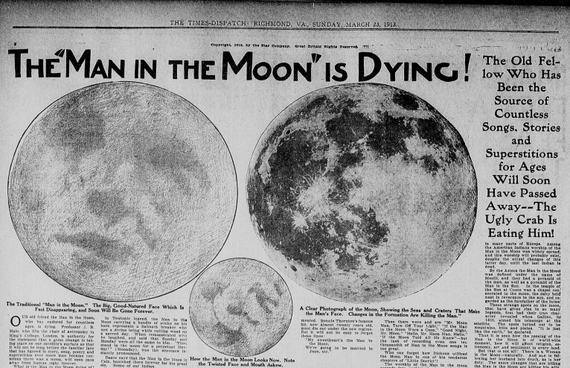

A century ago, scientists claimed the man in the moon was "dying," that profound formational changes on the lunar surface would wipe out the famous pareidolic face, causing a "distinct loss to sentiment, tradition, literature and commerce the world over," according to the Times-Dispatch of Richmond, Virginia.

For most of human history, landing on the moon seemed improbable enough that it became a sort of shorthand for talking about things that weren't likely to happen. When humans finally accomplished the feat, 45 years ago on this date, all that changed. Landing on the moon wasn't a marker of something that couldn't be done but the opposite.

And it was through that almost unbelievably grand accomplishment that the public's focus on the lunar surface became obsessively granular. By then, we knew not to expect roaming space pachyderms, so we focused on the details—mundane on our own planet, remarkable off of it—that could be known only to those who made the trip. Like moon germs: After the first landing, astronauts were quarantined for three weeks so that scientists could test them for lunar disease. (Several blood tests later, no abnormalities were found.)

People were captivated by the stuff the moon was made of, the floury abrasive particles that caked on the boots of astronauts who became heroes. And, thus began Earth's obsession with the physical pieces of the moon that, after eons of gazing skyward, humans had finally touched.

Moon dirt smelled of gunpowder and tasted "not half bad," NASA quotes Apollo 16 astronaut John Young as having said. (Outer space, on the other hand, smells like "wet clothes after rolling in snow," American astronaut Reid Wiseman recently tweeted.) Buzz Aldrin remembers the lunar surface as having felt like "moist talcum powder" underfoot. Moon dust even caused "extraterrestrial hay fever" for some astronauts, NASA said.

These days, plenty of people seem to have moved on from their romance with the moon. Aldrin and others are focused on Mars as the next great frontier. After all, humans haven't set foot on the moon in more than 40 years. It's unclear when or whether we'll ever go back, though there are those who haven't given up hope. And so we're back to gazing at the moon from here on Earth, wondering about what it's like up there today. The last astronauts on the moon left garbage behind. They left their footprints, of course, too. And scientists believe those imprints—planted in another era by long-since retired moon boots—could last for millions of years amid the craters, faint reminders that the sooty surface of our favorite satellite isn't so far from home.