In early June, a small delegation of Guardian developers and journalists made their way from London and New York to the MIT Media Lab in Boston for Hacking Journalism, a “hackathon to rethink how we create, disseminate, and consume media”.

Over the course of a weekend, we got to meet nice people from the Boston Globe, as well as freelance hacks, hackers and thinkers of all sorts. There were also people from news-related startups like embed.ly and parse.ly, among others.

Lightning talks

The event started on Saturday with a series of lightning talks on a few different topics.

Of particular note, Sensor Journalism, Uncensored by Lily Bui (slides) described how journalists could use data from sensors measuring noise, pollution, heat or other levels to tell a story on environment, public health, etc.

Typically, the data can be crowdsourced via various services like Cicada Tracker, iSeeChange or Ekuatorial, so journalists can start to discover new stories from sensor data. There are also more and more low-budget means to collect your own data (apps like Sensor Drone, RIFFLE, Noise Watch).

For the future, she foresees a democratization of data gathering and a return to “small data”, focused on local impact or civic action, with challenges around data privacy and ethics.

Next up was Matt Carroll, the new head of the “Future of News initiative” at the Media Lab and one of the organisers of the event. He presented 5 Minutes, 5 Top Media Stories, 5 Hot New Media Trends:

1. “Never mind digital first... it's mobile first”

We all know it, the mobile market share is around 50% and growing.

2. Atomisation of news

An idea dear to Jeff Jarvis: break the news into small digestible pieces, rather than a long legacy inverted pyramid article. A trendy topic, especially in the US community, which has spawned a few recent projects of note:

- Fission.io, an open source tool for journalists to collect and manage news atoms, sort of a modern take on the reporter's notebook.

- OnRamp.it, an “open ecosystem for news atoms” by Stanford University, aiming to serve both news organisations and readers through an open protocol.

3. Delivery & distribution

Just in time news, news you get before you know you need it. Obvious hint at Google Glass, or its future successors, such as the Android watches just released at Google I/O.

4. The medium shapes the message (for readers)

People consume news in a much wider variety of contexts than they ever did before: on their phone while on the go, sneakily at work in a background window or in the middle of trendy granola pictures from their friends on Twitter.

5. The medium shapes the message (for newsrooms)

Mobile is a different language to desktop, and content producers rely increasingly on simpler layouts and (oft-questioned) lower information density.

Matt also warned that commodity news is losing its value. Rather than all covering the President’s speech, news organisations would be better off investing in investigative pieces. At the same time, brands stand out and the days of the solo reporter are over.

Matt also presented the Future of News initiative and how he is now working with students to develop tools for the newsroom.

Alexis Hope and Kevin Hu showcased their project FOLD, a user-interface to navigate context for complex stories. For instance, when reading about the housing crisis, Crimea or Higgs Boson, we often lack the context and feel stupid. Their idea is to help storytellers make their work more accessible, and help readers better understand the context.

In their demo, the vertical axis tells a story in reverse chronological chunks, while additional context (explainer, video, image) can be browsed horizontally for each chunk. An open beta is expected to launch by the end of summer 2014.

Project presentations

After two days of frantic work, it was time for each team to present their work. We have highlighted a few below, but the full list with descriptions is worth a read.

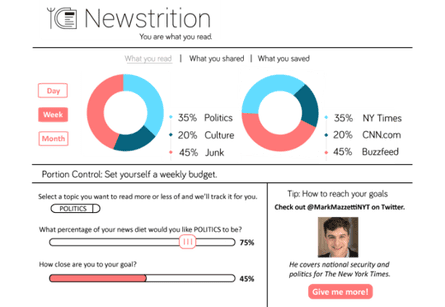

Newstrition (“You are what you read”)

Health and fitness apps are a big deal at the moment, enough so that Apple have added an integrated Health app to iOS 8. Could we apply something similar to news? How “healthy” is your reading history? Are you reading too much “light” content and not enough hard news?

Newstrition is a Chrome extension to help you gauge that. As you read it keeps track of the type of content you’re reading, and presents that back to you as a pie chart. It figures out what kind of content you read in a fairly naive manner (pattern matching on URLs), but the team said that if they were to expand it into a full project, they would look at a more robust solution. They also suggested that they might add a feature allowing you to set targets for yourself – e.g. I want to read more articles about politics – and track how well you’re doing.

The ratio of negative to positive news is roughly 17:1. But are you always in the mood for heavy news? The idea of Bomb Popper is it allows you to read news based on your current mood.

The hack used the Guardian's Content API as source of content and crowdsourced the mood of each article (happy/sad classification). Given our rich tagging vocabulary, it wouldn’t be such a stretch for us to annotate our content at the source, although it may be more focused on “colour” (dark, light) than mood, which is subjective (Boris Johnson eaten by a grue – happy or sad story?).

If you know a reader’s location, can you automatically localise an article’s content to be more relevant them? Datacle is a JavaScript library that tries to make that as simple as possible. In your article you write tags that the library replaces automatically with data from a Geolocation-based dataset, e.g. if the article was about a particular bill that had been voted on in Congress, you could insert a tag that would tell the reader which way their local senator had cast their vote.

Triangle

Similarly to what Datacle does for geolocation, Triangle fetches your social data to explain how a piece of news relates to you, e.g. a long-time friend now lives in that far away city that experienced an earthquake.

InLine

A service to comment on copy imported from any URL, paragraph by paragraph. Besides proofreading, it can be used to provide context alongside content, such as definitions or concept explainers.

Main Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal is usually guarded by a paywall, but as with other paywalled sites, if you come in through Google it lets you read the article. This hack enabled users to bypass the WSJ paywall by faking referer (sic) and pretending to be Google. People were really excited about this and it won two prizes.

Take away: journalists like hacking paywalls?

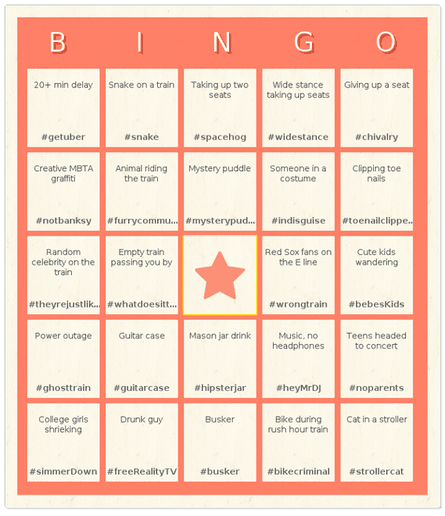

MBTA Bingo

MBTA Bingo is a hashtag-driven photo-sourcing game. Tweet @mbtabingo, and the MBTA bot tweets back with a bingo card, where each square is a description of something you have to take a photo of, with an associated hashtag.

When you tweet @mbtabingo with the relevant hashtag and photo, it inserts that picture into your bingo card and tweets it back at you. In the meantime it accumulates a database of the photos it has of particular things. You could use this to crowdsource images during an event. At the Guardian we take crowdsourcing of content seriously, and have a project dedicated to that – Guardian Witness.

They're watching me

theyrewatching.me aggregates the Twitter feeds of Glenn Greenwald, Jacob Applebaum, and others reporting on the NSA after the Snowden revelations. This takes the idea of “following a story” and applies it to a well-known case.

Accio!

The hack from the Guardian team, which allowed journalists to target readers by location or reading history and ask them if they want to participate to an anonymous survey related to an ongoing report. Based on their answers, they could be targeted again for more questions at a later time or asked if they would accept to be contacted directly.

A further idea we didn't get time to explore much was the use of a live geo-targeted component on our website that would collect anonymous data points from our readers, by asking them for information or opinion and collecting it alongside their geolocation. For instance, target people in a city where there is a large demonstration and ask if they are being kettled, or get all European readers of the Eurovision liveblog to rate each act live. The data could then be immediately available as graphs (heat map, bar chart) embeddable in a liveblog. Think using willing readers as crowdsourced human sensors for the reporting.

All in all, the organisers deserve a big thank you, in particular Matt Carroll, Lindsey Wagner, and the ever exceptionally groomed Kawandeep Virdee from embed.ly. Hacking Journalism was a great success in bringing coders and writers together to formulate hopeful, original and sometimes funny visions of what tomorrow’s journalism could be.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion