Anyone who thinks American suburbia is boring doesn't know the Westchester County of John Cheever. She does not know the mysteries of Shady Hill, nor the sorrows of gin. He has not gone swimming with Neddy Merrill, nor taken the 5:48 home with Blake. For Cheever, the fusty manses north of New York City were full of wild fantasies and private joys. The lawns, the pools, the couples arguing over lukewarm bourbon, the small moments of middle-American grace: these belonged to Cheever, and he to them.

In 1964, Time magazine called Cheever "Ovid in Ossining," because he saw what he called in one story "the pain and sweetness of life" as fully as the Roman poet had two millennia before him. Ovid, of course, spent the last decade of his exile from Rome in the desolation of Tomis (today, Romania). Cheever exiled himself, leaving Manhattan in 1951 for Westchester County and never returning. That journey into the manicured countryside beyond the Bronx would define his career more than his impoverished Massachusetts childhood or posh Sutton Place, where he lived while becoming famous for his New Yorker stories.

By 1961, when he bought a house at 197 Cedar Lane called "Afterwhiles" in the village of Ossining, about an hour north of Manhattan, he was probably as famous as any writer in America. The town is the home of Sing Sing prison, which would become the inspiration for Cheever's 1977 novel Falconer. Don Draper lived here, too, at 42 Bullet Park Road, a tip of the fedora to Cheever's 1969 novel Bullet Park (Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner has been open about Cheever's influence on the show.)

Cheever died in 1982, having lived there for 20 years. Then his widow, Mary, occupied it alone, painting and writing (her bright studio is attached to the main house). Then, last spring, she died at 95. None of the three Cheever children wants to live there: Susan, a successful writer who just published a well-received biography of the poet E.E. Cummings, lives in Manhattan; Fred is a law professor in Denver; Ben, also a writer, lives in New Jersey's Hudson County with his wife, New York Times book critic Janet Maslin.

So for $525,000 and $25,000 a year in taxes, these six acres can be yours, provided you don't mind living in the relative seclusion of northern Ossining (there are two other houses, spaced far apart, in the greater confines of the "Afterwhiles" estate). Though Route 9A runs right past the house, it is occluded by a heavy growth of trees, and about as audible as the autumnal gusts of wind. There is a Metro-North train to Ossining, but you won't be near it. This is a place for someone not terrified by solitude.

The house "isn't plaqued," either, says Bitsy Maraynes of Houlihan Lawrence, the broker handling the sale. That means it lacks historical landmark designation, though portions of the house, originally on the Van Cortlandt estate, go back to 1795. A hedge-fund huckster might sweep up the property, tear down the house and erect an angular glass temple to Mammon. That would be tragic but also, somehow, Cheeverian, a triumph of human vanity that would surely end strangely, perhaps with the aforementioned magnate commencing a steamy affair with the undocumented immigrant who polishes his windows.

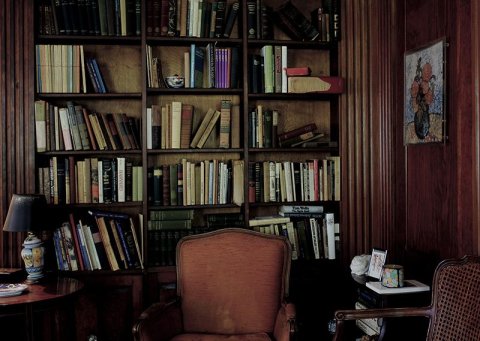

"I try to forewarn people: It needs a lot of work," Maraynes told The Journal News of Westchester. That work could easily run into the six figures. Built into a steep hillside, the house welcomes you with a stacked porch that is like a set of smiling teeth. (The teeth could use a little whitening, but it's a smile nevertheless.) There are planked wooden floors and handsome wooden paneling, warrens of rooms that look as if they would be especially cozy in winter (eight rooms, three bedrooms and three baths, for the seriously curious). A faded grace pervades. Cheever deemed it a "picturesque old dump" upon moving in, according to Blake Bailey's fine biography of the writer. That's a little cruel, especially since Cheever came to love the place, but more than a couple of trips to Home Depot await whoever buys 197 Cedar Lane.

And while the house isn't in the public trust, it has too much history to be allowed to disappear. I toured the place with Susan, a sunny, middle-aged woman who has written eloquently about her childhood in Home Before Dark; she seemed overwhelmed by the realization that this house, which she loves, would soon pass from her family's hands. I kept asking the one question obviously worth asking—What was it like here?—and she kept wracking her mind and returned to a single word, "magical." Once, she managed "enchanting," then sighed at her inability to say much more.

But those are good words. This, after all, is where Ralph Ellison played Bach on the recorder, where Philip Roth and Saul Bellow reposed. There is the pantry where her father kept his famous stash of booze. Robert Penn Warren, John Updike—they all came to 197 Cedar Lane. They would talk literature and maybe go for a swim at one of the local pools, whose proliferation in suburban backyards became the basis for Cheever's most famous story, "The Swimmer."

The house in Ossining was not Cheever's first flirtation with suburbia. In 1951, John and Mary moved into a house on Beechwood, the vast Westchester estate of Frank A. Vanderlip. Cheever referred to this, derisively, as "the chicken house in Scarborough," but it is here that he wrote the famous stories that would make up the celebrated 1959 collection The Housebreaker of Shady Hill and Other Stories.

Others wrote about suburbia at the time, too, with Richard Yates's Revolutionary Road standing as a chilling testament to that time (though perhaps an overwrought one). Yet nobody wrote about suburbia like Cheever, as John Updike noted in his elegant eulogy in The New Yorker in 1982: "Only Cheever was able to make an archetypal place out of it, a terrain we can recognize within ourselves, wherever we are or have been. Only he saw in its cocktail parties and swimming pools the shimmer of dissolving dreams."

It was Mary who found the Ossining house, having tired, by 1960, of "living in someone else's playpen." They bought it for $37,500, after which Cheever went to Los Angeles to try his hand at screenwriting. In Los Angeles, according to Bailey's biography, Cheever would have one of the covert homosexual affairs that caused him so much anguish, with the writer Calvin Kentfield.

Cheever returned to New York in a "panic of self-hatred," Bailey told me over the phone, taking a break from the authorized Philip Roth biography he is currently writing. The house in Ossining would serve, according to Bailey, to burnish Cheever's image as a "Westchester paterfamilias," a Hudson River Valley WASP who was really a Massachusetts pauper with a complexly cloven heart. While his fame would continue to grow—The Stories of John Cheever would win the Pulitzer Prize in 1979—he could not resolve his bisexuality and sought to quench his psychic anguish in alcohol.

His consumption reached its ruinous apotheosis at the Cedar Lane house. "I want to sleep," he wrote in 1972, in journals published after his death. "I seem to make the remark with some serenity. I am tired of worrying about constipation, homosexuality, alcoholism, and brooding on what a gay bar must be like. Are they filled with scented hobgoblins, girlish youths, stern beauties? I will never know."

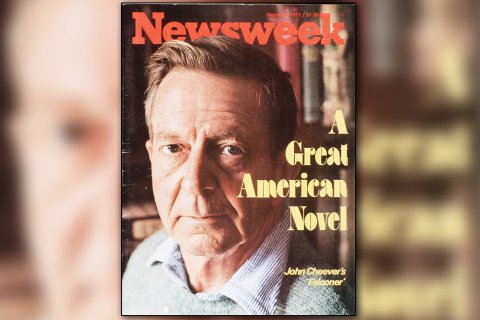

Unlike his brother, Fred, who succumbed to alcoholism, Cheever quit drinking in 1975, devoting himself seriously to Alcoholics Anonymous. Two years later, he published Falconer, based on his experience teaching at the nearby prison (he had started doing so in 1971, after deciding that he'd "exhausted his old landscapes"). Joan Didion called the novel "extraordinary" in The New York Times. This magazine put Cheever on the cover, calling Falconer a "great American novel." Five years later, Cheever died of cancer.

"Afterwhiles" remains full of memorabilia, seeming to have changed little in the years between John's death and Mary's last spring, so that it can feel less like a house than a house museum: a Kipp's Pharmacy box from 1957; an issue of the Paris Review from 1993, a yellowed manuscript page, a bottle of Scotch. Susan and I open a package that appears to have been sent a rather long time ago. It is full of paperback copies of Cheever's stories in Romanian. We think it is Romanian, at least. She hands me one. She finds an old Russian icon (Cheever was beloved in the Soviet Union) and decides to keep it. We wrap it gingerly in a tablecloth.

While some of the remaining objects—a landscape painting, a typewriter—have been claimed by one of the Cheever siblings via Post-Its, some of this stuff has nowhere to go, which means that the next owner of Afterwhiles could inherit a good portion of Cheever's possessions and, by extension, 20th century American literary history.

"It can stay, it is for sale. We have all already taken what we want," Susan later wrote to me in an email when I asked whether prospective buyers could claim the Cheever memorabilia left behind. "Imagine the stories they would write!"