/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/50237245/Vaginal_Photoplethysmograph.cropped.0.png)

Sex is one of the most primal, most pleasurable, and — from an evolutionary standpoint — most essential of human functions. So it makes sense that biologists, psychologists, and other scientists would want to study it.

But researchers in this field have a huge obstacle: Sex is also one of the most private of human activities. That makes it hard to study.

So how do sex researchers manage to get good data?

In the early days, they simply talked to people. This was sex researcher Alfred Kinsey's main technique for his formative studies in the 1940s and '50s. And people were happy to share an incredible amount of information.

Kinsey and his team at Indiana University conducted more than 18,000 extensive interviews, with the simple and unprecedented goal of thoroughly documenting sexual behavior in the United States.

Some of their major — and controversial — findings included that men and women commonly engaged in premarital sex, oral sex, and masturbation. They also reported that 37 percent of men had had a same-sex encounter that included orgasm.

The interviews also helped the team develop a new way to think about sexual orientation: Instead of discrete categories of homosexuality and heterosexuality, they proposed the sliding, 0-to-6 "Kinsey Scale."

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6858209/Michael-Sheen-and-Lizzy-Caplan-of-Masters-of-Sex_gallery_primary.0.jpg)

The Showtime series "Masters of Sex" is a fictional drama about researchers Masters and Johnson, who did critical work on sex starting in the 1950s.

Starting in 1957, the team of William Masters and Virginia Johnson (of Washington University in St. Louis) directly observed hundreds of men and women masturbating and having sex in their laboratory, while documenting these participants' sexual anatomy and physiology.

Their studies popularized the idea that sexual response starts with excitement, a plateau, an orgasm, and a resolution phase. (However, only a subset of humans are comfortable having sex in front of spectators, which was definitely a limitation of their methods.)

But that wasn't the only thing going on then. Also in the 1960s, researchers began developing new tools to objectively measure erections of the penis and arousal in the vagina and labia. As these instruments improved, they could pick up small changes in arousal that a human observer would probably miss.

Today, sex researchers use a wide variety of methods to study human sexuality. Participating in a sex study could include any of these (and others): filling out a survey online, having sex with your partner in a lab, watching pornography while instruments measure your physical arousal, testing if a drug helps with your sexual problem, or masturbating in an MRI machine.

Here's a rundown of four common methods of modern sex science:

1) Hook people up to machines — and measure arousal

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6858141/Mercury-strain-gauge.cropped.png)

A mercury strain gauge, which can measure the changing circumference of a penis. (Sarah Sudhoff)

Modern sex researchers employ a wide array of seemingly bizarre tools that can help them objectively measure physical arousal — often in response to masturbation or erotic imagery.

These tools can be especially helpful because what people say they find arousing and what actually arouses their genitalia aren't always the same.

The vaginal photoplethysmograph in the photo at the top of the page, for example, measures the blood volume and pulse of the vagina's blood vessels.

Another tool that's sometimes used is one that's essentially a thermometer for the labia. And penile strain gauges continuously measure changes in penis circumference.

One big benefit of these devices is that participants in sex studies can use them by themselves — no researcher has to touch their private parts. That has helped sex researchers attract a broader sample of test subjects with a wider variety of comfort zones, making for more representative science.

"You would be surprised how many people from all different backgrounds are willing to participate in this," Erick Janssen told me. He's a sex researcher at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University. "[These tools] opened up this kind of work to a lot of people."

One thing that sex researchers have discovered using these tools is that what women say makes them aroused often differs from what their vaginas say, whereas men's reporting matches up better.

For example, heterosexual women have shown equal physical arousal from watching videos of women masturbating or men masturbating. Heterosexual men respond more to females on screen. This kind of data seems to support the idea that women's sexuality is generally more fluid than men's. (Researcher Alice Dreger has a nice summary and critique of these studies here.)

2) Simply ask people about sex

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6857989/speech-bubbles-cropped.jpg)

Plenty of researchers still do things the old-fashioned way and simply ask lots of people about sex through interviews and surveys. One major benefit of surveys is that they can identify trends across a broad population.

For instance, the 2010 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior surveyed 5,865 adolescents and adults. And it spotted some intriguing things.

It found that single teens were more likely to use condoms than single adults. And that adults using condoms were as likely to rate their sexual experience as pleasurable as those not using them.

The survey also found a "fake orgasm gap": 85 percent of men reported their partner had an orgasm last time they had sex, while just 64 percent of women reported having one (that gap was too big to be explained away by men who had had sex with men).

That said, asking people how they feel or think is always tricky because there's room for people to skew their answers — consciously or unconsciously — to make them more socially acceptable. (For example, my answer of whether I went to the gym today is probably more reliable than my answer of how many times I went to the gym in the past month. I'm likely to overestimate the latter.)

So for smaller studies, sex researchers often get quicker self-reports, in the hopes that this will be more accurate. Researchers might ask participants to use real-time diaries or put information into smartphone apps during their everyday lives instead of doing retrospective interviews later.

Likewise, in a laboratory experiment, researchers could ask people to rate how sexually aroused they feel in the moment while, say, watching porn.

3) Scan people's brains during sex

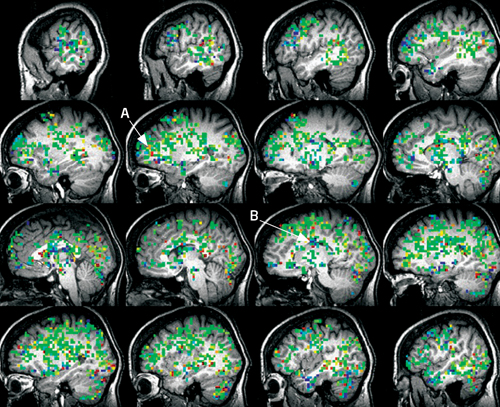

(Barry R. Komisaruk via New Scientist)

Brain imaging is one of the newer tools for studying sex. One example is functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI, which measures changes in brain activity in real time.

These kinds of studies often involve someone lying in the machine while thinking about something in particular, looking at erotic imagery, masturbating, or being sexually stimulated by someone else.

These sorts of brain scans can sometimes lead to overblown claims by researchers and the media alike. A big problem here is that there's currently no particular brain area or pattern that reliably and specifically measures sexual arousal.

That said, brain imaging can still be useful. For example, Barry Komisaruk, a psychologist at Rutgers University, has been using fMRI to study what happens in the brain during an orgasm. He found that the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in higher order conscious functions, seems to have more activity during orgasm. (Others have found less activity.) This kind of work might someday help people who have difficulty having orgasms.

4) Measure people's skin conductance during sexual arousal

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6857995/galvanic-skin-conductance-response-kit.jpg)

Skin conductance, also known as galvanic skin response, has been known for long enough that there are even kits to measure your own, like this one from Make.

Another long-standing technique, which has been in use for decades, is to hook someone up to electrodes and measure tiny changes in how much someone has been sweating.

Changes in psychological states (including general arousal and perhaps attention) cause tiny changes in sweat. And changes in sweat can be picked up as tiny changes in how the skin conducts electricity, also called skin conductance.

Because this method can work with subjects fully clothed, one major benefit is that it might seem more inviting to more participants.

However, skin conductance isn't specific to only sexual arousal, but arousal in general. "You may find changes during sexual arousal, but also during other emotional states," Janssen told me. But it can still be handy for sex researchers, especially when used in parallel with other methods.

Special thanks to artist Sarah Sudhoff for letting me use her images, which I had to crop to look decent in this layout. You can see them in their full glory as part of her amazing photo series on sex research tools.

This story was originally published on July 1, 2014.