University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee ecologist Harvey Bootsma holds a rock coated with quagga mussels, collected on a dive into Lake Michigan off Shorewood. ERIN CAUGHEY

Zebra mussels, quagga mussels have turned the lakes' ecosystem upside down

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee ecologist Harvey Bootsma holds a rock coated with quagga mussels, collected on a dive into Lake Michigan off Shorewood. ERIN CAUGHEY

June 1, 1988, the day everything changed for the Great Lakes, was sunny, hot and mostly calm — perfect weather for the young researchers from the University of Windsor who were hunting for critters crawling across the bottom of Lake St. Clair.

Sonya Santavy was a freshly graduated biologist aboard the research boat as its whining outboard pushed it toward the middle of the lake that straddles the U.S. and Canadian border. On a map, Lake St. Clair looks like a 24-mile-wide aneurysm in the river system east of Detroit that connects Lake Huron to Lake Erie. Water pools in it and then churns through as the outflows from Lakes Superior, Michigan and Huron swirl down into Erie, then continue flowing east over Niagara Falls into Lake Ontario, and finally out the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic Ocean.

The water moves so fast through Lake St. Clair because the lake is as shallow as a swimming pool in most places, except for an approximately 30-foot-deep navigation channel down its middle. The government carved that pathway long ago to allow freighters to sail as far inland as Milwaukee and Duluth.

When water levels are low or sediment is high, the channel isn't deep enough and sometimes ships have to lighten their loads to squeeze through. That means dumping water from ship-steadying ballast tanks — water taken onboard outside the Great Lakes, water that too often and for too long swarmed with exotic life from ports around the globe.

As the three young researchers were drifting over a rocky-bottomed portion of Lake St. Clair on that steamy Wednesday morning, Santavy decided to drop her sampling scoop into the cobble below. She was hunting for muck-loving worms but figured she'd take a poke into the rocks because, well, to this day, she still doesn't know.

"I can't even explain why it popped into my head," Santavy says. "I thought — if we get nothing, we get nothing, and I'll just mark it off that this is not an area to sample."

Up came a wormless scoop of stones, the smallest of which were pebbles not much bigger than her fingertips.

But there was something odd about two of these tinier stones. They were stuck together.

She tried to muscle them apart but she couldn't.

Then she realized that one of them was alive.

Slamming shut the doors

A watershed moment has arrived for the Great Lakes.

After decades of regulatory paralysis, a federal judge has forced the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to begin requiring overseas ships to decontaminate their ballast water before discharging it into the five lakes that together span a surface area the size of the United Kingdom.

Despite their vastness, for thousands of years the inland seas above Niagara Falls were as isolated from the outside world as a Northwoods Wisconsin pond. That all changed in 1959. The U.S. and Canadian governments obliterated the lake's natural barrier to invasive fish, plants, viruses and mollusks with the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway, a system of channels, locks and dams that opened the door for ocean freighters to sail up the once-wild St. Lawrence River, around Niagara Falls and into the heart of the continent.

Small boats had access to the lakes since the 1800s thanks to relatively tiny man-made navigation channels stretching in from the East Coast and a canal at Chicago that artificially linked Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River basin.

But the consequences of opening a nautical freeway into the Great Lakes for globe-roaming freighters proved disastrous — at least 56 non-native organisms have since been discovered in the lakes, and the majority arrived as stowaways in freighter ballast tanks.

These invaders have decimated native fish populations and rewired the way energy flows through the world's largest freshwater system, sparking an explosion in seaweed growth that rots in reeking pockets along thousands of miles of shoreline. The foreign organisms are implicated in botulism outbreaks that have suffocated tens of thousands of birds on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. They are among the culprits responsible for toxic algae blooms on Lake Erie that threaten public water supplies.

The hope is the new ballast discharge regulations will shut the door to new invasions.

The reality: The Environmental Protection Agency has already acknowledged they are not stringent enough to do that job.

The agency blames a lack of technology to adequately disinfect ballast tanks. Critics blame a lack of resolve in getting tough with the relatively tiny overseas shipping industry that has done so much damage to this singularly important natural resource; an average of fewer than two such ships visit the lakes each day during the Seaway's nine-month, ice-free shipping season.

"We can do much better," says biologist Gary Fahnenstiel, who spent his career chronicling the ecological unraveling of Lake Michigan for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "If we really care about the lakes."

Solving the Seaway ballast problem isn't just about the Great Lakes, because the invaders have a history of making their way into waters across the continent. Out West, where Great Lakes invasive mussels are spreading as fast as boats are towed from lake to lake, states now have laws to throw people in jail and fine them thousands of dollars for transporting the same species Seaway freighters dumped on the continent with impunity.

Great Lakes advocates predict the bubbling frustration out West over the Seaway's role in their troubles will erupt if — or when — Seaway ships unleash yet another invader.

"The industry has had this grace period to find solutions," says Phyllis Green, superintendent of Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior. "The grace period they have been given will hit the fan when they find the next one."

The pressure is mounting inside the Great Lakes basin as well, because even as the EPA leaves this front door to the Great Lakes cracked open, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is under fire from Congress to shut the back door — the Chicago canal system that is the prime pathway for Asian carp to invade the lakes. Rebuilding the natural divide between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River basin is a project that likely would take years and cost billions of dollars.

But it begs the question: Why spend all this money to close the back door if we aren't going to shut and seal the front door as well?

Building a barrier to protect the upper Great Lakes from Seaway invaders would actually be simpler than restoring the natural watershed divide at Chicago. In fact, such a barrier already exists.

It's called Niagara Falls.

'It's crazy to go on ... studying this'

Santavy showed a fellow scientist aboard the research boat her living "stone" with wavy bands that allowed it to blend into the rocks below. Both knew it was some kind of clam or mussel, but the dime-sized mollusk looked like nothing Santavy's colleague had seen before. This was remarkable. He was a graduate student whose job was to study freshwater clams of North America.

They motored the boat to shore and brought the curious shell back to the university, where the biology professors also were flummoxed.

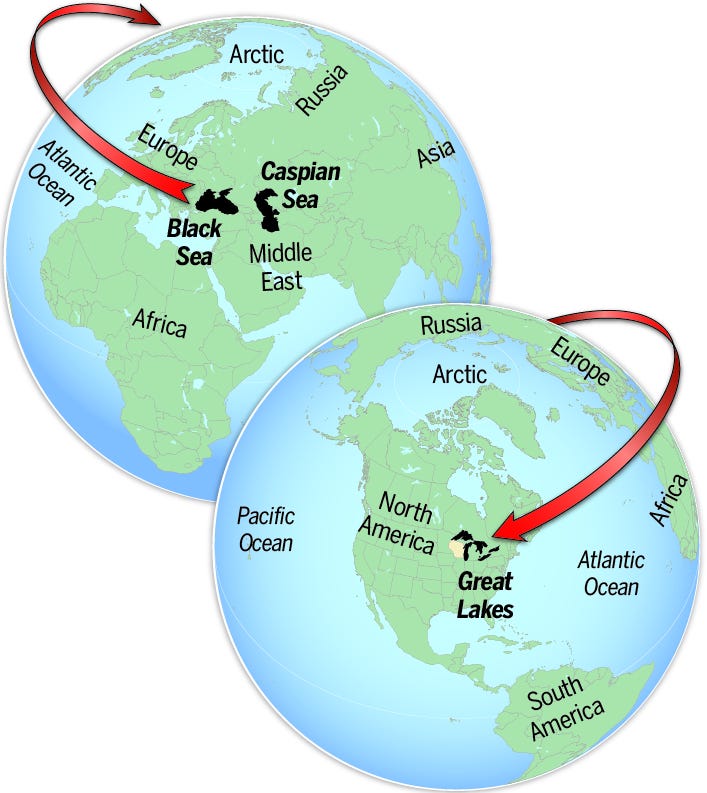

The specimen was driven a few hours over to the University of Guelph outside Toronto, where an international mussel expert recognized it immediately as Dreissena polymorpha, the zebra mussel. This was not good news. The species, native to the Caspian and Black Sea regions, was famous on the other side of the Atlantic for its ability to glue itself to any hard surface in wickedly sharp clusters that bloody boaters' hands and swimmers' feet, plug pipes, foul boat bottoms and suck the plankton — the life — out of the waters it invades.

The mussels had already colonized rivers and lakes across Western Europe thanks to an extensive network of canals and locks that, like North America's Seaway, had allowed biological trouble to course through a continent like viruses in a bloodstream. Hungary succumbed to an infestation in 1794, London in 1824. Rotterdam fell in 1827 followed by Hamburg in 1830 and Copenhagen in 1840. The ecological menace had moved on to Switzerland, Finland, Ireland and Italy by the 1970s.

Then in 1988 this specimen turned up in Lake St. Clair, some 3,000 miles from its closest known colony. A zebra mussel has something of a "foot" that enables it to drag itself across a lake bottom, but the fastest adult zebra mussel can only trundle along at a rate of about 14 inches per hour.

Scientists knew the only plausible way Santavy's mussel could have made the trip across the Atlantic and into the Great Lakes was in the friendly confines of a freighter ballast tank.

The discovery of the single shell might have meant little initially to the young researchers who found it, but seasoned ecologists knew the doom it foretold, like radiologists spotting a telltale speck on an X-ray.

Distressing as the news was, nobody should have been surprised.

As early as the late 1800s, naturalists had recognized the zebra mussel as an invasive species juggernaut, according to James Carlton, a Williams College biologist who has tracked historical warnings of mussel troubles.

"The Dreissena is perhaps better fitted for dissemination by man and subsequent establishment than any other fresh-water shell," English zoologist Harry Wallace Kew wrote in 1893. "Tenacity of life, unusually rapid propagation, the faculty of becoming attached by string byssus to extraneous substances, and the power of adapting itself to strange and altogether artificial surroundings have combined to make it one of the most successful molluscan colonists in the world."

A second warning came in 1921 from Charles Johnson, curator of the Boston Society of Natural History.

"The possibility of ... the zebra mussel being introduced (to the United States) is very great. There is entirely too much reckless dumping of aquaria into our ponds and streams. A number of foreign freshwater shells, etc., have been introduced this way. Why not the mussel?"

Another alarm came in 1964, five years after the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway.

"There is the real possibility that Dreissena polymorpha will eventually become established in the North American continent despite all efforts to prevent introduction of exotic species," cautioned biologist Ralph Sinclair.

A final alarm came in 1981 when a group of scientists took the time to see what was lurking in the ballast tanks of foreign freighters bound for the Great Lakes. They found the ships were basically floating ecosystems, teeming with life sucked up from ports around the globe.

The researchers specifically mentioned zebra mussels as a primary threat to invade.

The U.S. and Canadian governments did nothing in response.

The next year, in 1982, overseas ships were blamed for bringing into the lakes the spiny water flea that has ravaged native zooplankton and the little fish that depend upon them. The year after that, overseas ships were identified as the culprit for the arrival an exotic tubificid worm. In 1986, a fish called the Eurasian ruffe was discovered in Lake Superior.

Two years after that, in 1988, news of Santavy's zebra mussel find reached the public with a front-page story in the Windsor Star. It declared that a novel "zebra clam" might cost the region millions of dollars because of its ability to clog industrial water intake pipes.

"This guy hitchhiked inside a ballast tank," Paul Hebert, director of the University of Windsor lab where Santavy worked, told the reporter. "It's crazy to go on studying and studying this — we have to do something. We're getting new species in the lake all the time."

Santavy found just one mussel. Everybody knew there had to be more. They just didn't know how many.

A tiny foe, a giant mess

Tom Nalepa, then an ecologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, remembers making the three-hour drive from his office in Ann Arbor, Mich., to London, Ontario, in March 1989 to meet with 11 other scientists about the latest Great Lakes invader. It was already spreading faster than the North American scientists' ability to read up about it.

The researchers that day, in fact, couldn't even agree whether to call it a clam or a mussel. Conference host Ron Griffiths of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources took the diplomatic tack of referring to it as the "zebra mussel clam." The problem was there was almost no North American literature on the life cycle of the zebra mussel because — until then — there had been no North American zebra mussels. Scientists were gleaning what they could from research papers written in Russian, Polish and Danish just to figure out things like its preferred habitat, its temperature tolerance and its reproduction rate.

"A lot of the literature I've read is in another language, and I can only go as far as the abstract," Gerry Mackie, a mussel expert from the University of Guelph, confessed at the outset of the conference, a video tape of which was provided to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

The researchers turned on a carousel slide projector to look at how far the zebras had come since Santavy dropped her scoop to the bottom of Lake St. Clair just 10 months earlier. The room got quiet as the wheel stopped with a double clunk on each new image.

- An engine block found on the bottom of Lake St. Clair so encrusted with zebra mussels its piston holes were plugged.

- A Coast Guard buoy hauled in from Lake Erie coated with shells to the point that it was unrecognizable.

- A Great Lakes beach littered with bleached mussel shells lying open on their sides, like so many little mouths.

Then Griffiths turned on a videotape of a mussel-smothered ferry wharf on the Canadian side of Lake Erie. There were so many shells nobody tried to calculate how densely they smothered the pier's pilings and steel. It would have been like counting grains of sand on a beach.

"Man," ecologist Nalepa thought as he sat with his colleagues around tables littered with coffee cups and jars of zebra mussel specimens. "Nothing is going to be the same. Nothing."

There was some talk that day about how the mussels might affect native fisheries, but the scientists mostly worried about what the mollusks could do to the region's industries, given their ability to gum up pipes.

A biologist with a Michigan power utility showed another video that revealed the zebra mussels were beginning to gather in golf ball-sized clusters on the water intake pipes at the massive Monroe Power Plant on the western shore of Lake Erie. He predicted that, unchecked, the mussels could cost the plant hundreds of thousands of dollars. Per day. Griffiths, the conference host, told the group one of his biggest challenges was explaining to the public that the wave of shells washing across the region would not stay confined to the Great Lakes.

"Everybody on reservoirs or inland lakes, they just pass it off and they keep laughing at these guys because they're so small," he said. "Right now, there is no way anyone believes that a critter that small can cause any kind of problem."

By the end of the year, zebra mussels had turned up all across the Great Lakes, west to Duluth, south to Chicago, east to the St. Lawrence River below Lake Ontario.

A colony was also found in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. That meant the mussels were already making their way beyond the Great Lakes. Water samples showed zebra mussels' microscopic young, called veligers, were drifting in the current of the Chicago canal, which feeds the Illinois River, which in turn nourishes the Mississippi. It didn't take long before researchers at a sampling site were counting veligers coursing down a waterway in the heart of the continent at a rate of 70 million per second.

But the most ominous mussel development of 1989 made no headlines. Researchers on Lake Erie found what appeared at first to be a slightly different version of the zebra mussel.

It was, they would learn two years later, the quagga mussel.

Zebra mussels proved to be a pox on industries that depend on Great Lakes water, costing them billions of dollars over the last quarter century to keep pipes open and water flowing through everything from kitchen faucets to nuclear power plants.

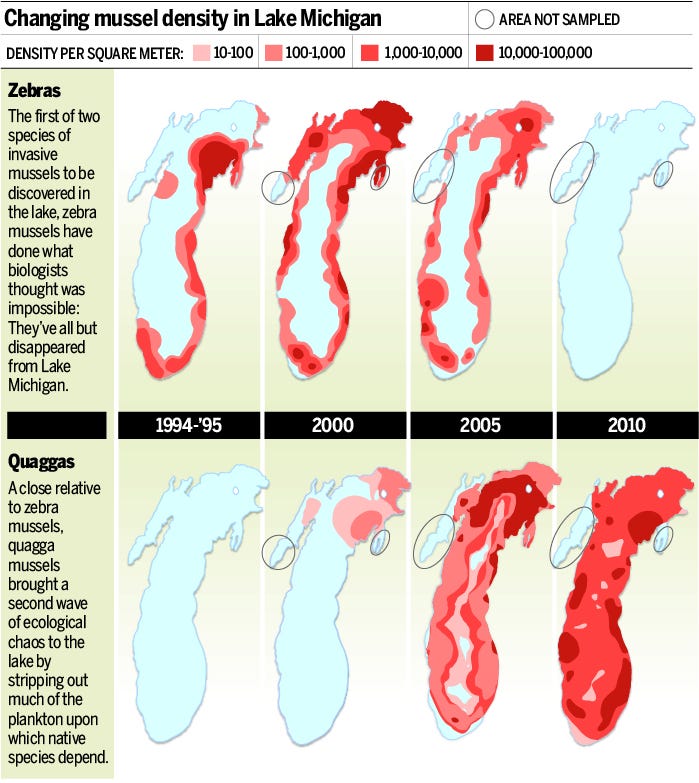

Yet the ecological damage wrought by zebra mussels is minor in comparison to their cousin the quagga. Zebra mussels have an impact on only a sliver of the overall ecology of the lakes because they are restricted to relatively shallow waters rimming the shorelines and need a hard surface to live on.

Quaggas aren't shackled to the shorelines. Unlike zebra mussels, which typically aren't found at depths beyond 60 feet, quaggas have been plucked from waters hundreds of feet deep and can thrive even in soft sediments. They can blanket almost the entire lake bottom. Zebras also feed only during the warmer months, while quaggas filter nutrients out of the water year-round.

Three years after quagga mussels were discovered in Lake Michigan, zebra mussels still made up more than 98% of the lake's invasive mussel population. By 2005, that relationship had flipped, with quaggas making up 97.7% of the invasive mussel population.

Scientists knew instantly back in 1989 that the arrival of zebra mussels was a game changer for the Great Lakes as we knew them.

Quaggas made it game over.

"Everybody used to say, 'Oh no! Zebra mussels!'" University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee biologist Russell Cuhel said after the quaggas mysteriously surged. "Well, zebras don't hold a candle to what these guys are going to do."

Hard to fathom

The public can comprehend the devastation of a catastrophic wildfire that torches vast stands of trees, leaves a scorched forest floor littered with wildlife carcasses and turns dancing streams into oozes of mud and ash. But forests grow back. The quagga mussel devastation of Lake Michigan is so profound it is hard to fathom.

"People look at the lake and don't think of it as having a geography. It's just a flat surface from above — and from there it looks pretty much the same as it did 30 years ago," UWM ecologist Harvey Bootsma said last fall as he prepared to scuba dive into the bizarre new web of life off Shorewood's Atwater Beach.

"But under water, everything has changed."

The mollusks now stretch across the bottom of Lake Michigan almost from shore to shore, piling on top of one another like a gnarly, endless plate of coral, clustering at densities exceeding 35,000 per square meter.

People might still think of Lake Michigan as an inland sea full of fish. It's now more accurate to think of it as an exotic mussel farm. The lake's quagga mass was estimated in one recent year to be about 7 times greater than the schools of prey fish that sustain the lake's struggling salmon and trout.

"People really don't grasp what has happened here," Bootsma explained as he squeezed into a rubber dry suit aboard a university-owned boat and prepared to dive to a research site a half mile off Atwater Beach.

He strapped on a scuba tank, climbed over the back of the boat, dropped into the frothing surf and plunged to the lake bottom 30 feet below. He might as well have landed on another continent, because under the surface Lake Michigan bears little resemblance to the freshwater wonder that left early European explorers awestruck by its abundance of lake trout, whitefish, sturgeon, herring and perch.

Invasive, mussel-gobbling round gobies are now the dominant fish species in the waters off Milwaukee. The invaders from the Black and Caspian seas that also arrived aboard overseas freighters thrive amid a shin-high forest of a plant called Cladophora, which needs three things to thrive: sunlight, nutrients, and a hard surface.

The mussels provide all three. Their plankton-stripping ability has dramatically increased the depths to which sunlight can penetrate. Their shells provide a surface on which the seaweed can grow and the mussels' phosphorus-rich excrement fuels the plant's growth. The result is an endless forest of brilliantly green, hair-like tendrils swaying in the current, invisible to anyone on shore — until it inevitably dies and washes up on the beach.

Bootsma finds the changes professionally interesting, but personally distressing. The 53-year-old attributes his career to summer days he spent as a child on Georgian Bay in northern Lake Huron, fishing for bass and perch and snorkeling to the rocky bottom to capture crayfish. He still remembers the pit he'd feel in his stomach when his family would pack up from their camping trips to Killbear Provincial Park and drive three hours south to their home in the steel mill city of Hamilton, Ontario.

"We'd go up there for the holidays and I'd be out in the sun and on the water every day all day, and I remember every time when it was the day to go home, I'd be close to tears," he said. "I still remember telling myself that when I grow up I'm going to get a job that will keep me on these lakes all the time."

Outside his office window at UWM's School of Freshwater Sciences are the grain elevators and coal piles that define Milwaukee's inner harbor. That harbor is connected to Lake Michigan, which is connected to Lake Huron, which connects to Georgian Bay. They all have different names, but in actuality they are the same lake, and the largest lake by surface area on the globe.

It is no longer the lake Bootsma fell in love with. He's known this in his head for years because of his almost weekly trips out to his research stations off Shorewood. But the changes really didn't hit him personally until he traveled back to Killbear Park a few years ago with his own children.

"I snorkeled some of the same areas that I did as a kid. I still saw some bass and that made me happy," he said. "But it was just devastating to see all the mussels and the gobies."

What's even more distressing for him is the idea that his children don't even know what they're missing.

Ecologists call it the "shifting baseline phenomenon" — a fancy way of saying that kids are getting cheated out of the lakes their moms and dads loved.

"It's just so sad to see it changing so much," Bootsma says. "This isn't the lake it was 25 years ago, and it's probably not the same lake it's going to be in 10 years."