Abstract

This systematic review examines the relationship between religion and sexual HIV risk behavior. It focuses primarily on how studies have conceptualized and defined religion, methodologies, and sexual risk outcomes. We also describe regions where studies were conducted and mechanisms by which religion may be associated with sexual risk. We included 137 studies in this review, classifying them as measuring: (1) only religious affiliation (n = 57), (2) only religiosity (n = 48), and (3) both religious affiliation and religiosity (n = 32). A number of studies identified lower levels of sexual HIV risk among Muslims, although many of these examined HIV prevalence rather than specific behavioral risk outcomes. Most studies identified increased religiosity to be associated with lower levels of sexual HIV risk. This finding persists but is weaker when the outcome considered is condom use. The paper reviews ways in which religion may contribute to increase and reduction in sexual HIV risk, gaps in research, and implications for future research on religion and HIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Religion influences various health outcomes including mortality, depression, and drug use [1–3] as a key factor that shapes behavior within many communities [4]. Early in the HIV epidemic, religion was considered detrimental to prevention efforts, as some religious communities considered AIDS to be a punishment for sin and opposed the public promotion of condom use and forms of sex education [5–7]. More recently, theologies of harm reduction have emerged within some religious groups [8] and religious organizations have become major HIV intervention partners in multiple countries [5].

Research on religion and HIV emphasizes the role of religion as a resource for people living with HIV, and suggests that religion is useful in helping individuals cope and find meaning [9, 10]. Less research is available on pathways through which religion may influence HIV risk behavior. Previous research that suggests religious tenets and practices impact HIV risk has focused on differences in HIV transmission across religious affiliations [11]. A number of studies have examined religious affiliation and HIV in Africa [11, 12], but none have examined associations between religious affiliation or religiosity and HIV risk worldwide. The limited emphasis on how religion may be a risk or protective factor, as well as an avenue for HIV prevention, may be related to contentions between religion and HIV preventative approaches described above. This may be shifting; however, as prevention efforts increasingly incorporate the importance of structural influences on risk, including gender inequalities, stigma, community networks, and behavioral norms, which may be influenced by religion. Attention to structural influences on risk highlights cultural, political, economic, and religious factors that may be related to risk behaviors, and emphasizes the importance of understanding unique risk contexts [13, 14]. Innovative approaches to HIV prevention that draw from local contexts through utilizing religious venues, partnerships, and frameworks (including, for example, an emphasis on specific values such as destiny, compassion, and purity) have demonstrated promise in reducing HIV risks [15].

A review of research to date is needed to consider how religion may be associated with HIV risk and protection and pathways by which religion may influence risk. This systematic review considers studies published on religion and sexual HIV risk since 1988. For the purposes of this paper religion is defined as including two primary components: (1) religious affiliation, and (2) a level of adherence to, participation in, influence of, or identification with a set of beliefs, referred to as “religiosity.” The review examines study methodologies, definitions and conceptualizations of religion, locations in which studies were conducted, and sexual risk outcomes associated with religion. We also discuss mechanisms that explain these associations and gaps in research on the relationship between religion and sexual HIV risk.

Methods

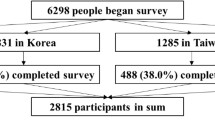

A total of 761 abstracts were reviewed through electronic searches of PubMed (n = 395), PsycInfo, Medline, and Biological Abstracts (n = 96), Sociological Abstracts (n = 56), and Web of Science (n = 214). Searches were conducted in February 2012, considering sources from 1985 through 2012. The search included three key areas: (1) HIV or AIDS, (2) sexual risk, and (3) religion (or religiosity, religious, church, Muslim, Islam, Christian, Christianity). Duplicate abstracts were excluded, as were reviews, dissertations, or abstracts focused on outcomes unrelated to sexual HIV risk.

Of the 157 remaining articles, six were excluded because they consisted of data presented in other papers in the sample. An additional 11 were excluded as they measured outcome variables not directly related to sexual HIV risk. Three articles were excluded for not specifying either a religious affiliation or a definition of religiosity. Data from each study was entered into SPSS version 20, after which frequencies and distributions were examined. We then conducted Chi square goodness of fit tests to identify differences between groups of studies (Fig. 1).

Results

Study Methodologies

The 137 studies included in this review were published between 1988 and 2012. Most studies employed cross-sectional designs (n = 113, 82.5 %). Twenty-two were longitudinal studies and two were randomized controlled trials. Four studies (2.9 %) included mixed methods or a qualitative component. Nearly one fourth (n = 33, 24.1 %) of the studies included national samples. Sample size varied from 33 to 216,000 individuals, with a mean of 4,714 and a median of 880. Four studies considered countries as the unit of analysis rather than individuals. Nearly equal numbers focused on adult populations only (n = 52, 38.0 %) and youth or young adults only (n = 53, 38.7 %); the latter included research with secondary school and college students. Another 23.4 % (n = 32) of studies considered mixed samples, including youth and adults, or a participant age range beginning below and exceeding 18. When age was not specified, the sample was considered to include only adults. Most studies were conducted with both women and men (n = 85, 62.0 %), while 28 studies (20.4 %) reported results solely for women and 24 (17.5 %) only included men.

Definition of Religion

Religion was conceptualized differently across studies. Most studies only examined religious affiliation (n = 57). Another group of studies (n = 48) only measured participant religiosity, without describing the religious affiliation of the sample. Finally, 32 studies measured both religious affiliation and religiosity.

Study Locations

Most studies were conducted in Africa (n = 61, 44.5 %), and North and South America (n = 53, 38.7 %), with 47 of the latter (34.3 %) conducted in the United States (US). Less commonly considered regions included Europe (n = 8, 5.8 %), the Western Pacific (n = 7, 5.1 %), South-East Asia (n = 4, 2.9 %), and the Middle East (n = 2, 1.5 %). Two studies were conducted in multiple regions (1.5 %).

Sexual Outcomes Associated with Religion

Because of differences in how religion and religiosity were presented, risk outcomes are detailed according to studies which describe: (1) religious affiliation only (n = 57), (2) religiosity only (n = 48), and (3) both religiosity and religious affiliation (n = 32).

Religious Affiliation and Sexual HIV Risk (n = 57 Studies)

Studies that only compared participants by religious affiliation differed from those that included religiosity in multiple ways. For example, the former were more likely to be conducted outside the US, with 61.1 % of articles conducted outside the US only measuring religious affiliation, as compared to only 4.2 % of studies conducted within the US (p < .001). Most studies conducted in Africa only compared outcomes of participants according to religious affiliation (n = 44, 72.1 %). Each of the four articles that considered countries rather than individuals as the unit of analysis described countries by their predominant religious denomination and did not describe religiosity.

Fifty-seven studies examined how sexual HIV risk varied according to religious affiliation, without measuring religiosity. As observed in Table 1, of 57 studies, 42 included participants who were designated as Muslims, 32 as Christians (including 3 as Orthodox), 27 as Catholics, 24 as Protestants, and 13 as ‘Traditional’ [11] or ‘Indigenous’ (two), all of which were conducted in Africa. Forty-one had designations beyond these categories, primarily ‘other’ or ‘other and none’ but nine studies identified other Christian faiths, five included the Hindu religion, three included Judaism, and Buddhist, Animist, and Agnostic affiliations were included in one study each. This review will compare studies according to the affiliations described.

Study outcomes included an examination of how affiliation is associated with condom use (n = 24), HIV positive status or prevalence (n = 19), having multiple partners or a partner outside of the primary relationship (n = 17), sexual initiation (n = 10), having sex with a commercial sex worker (n = 9), sexual experience (n = 6), STI prevalence or symptoms (n = 4), and other outcomes (n = 9), including general risk indicators. Over half of the studies in this group measured multiple sexual risk outcomes (n = 29, 52.7 %).

Fifty-one of the 57 studies found a particular religious affiliation to be associated with reduced sexual risk (n = 31), increased risk (n = 10), or both reduced and increased risk (through different pathways) (n = 10) for acquiring HIV. Six studies found no association between affiliation and sexual HIV risk (see Table 1). Protective effects were found within the following affiliations: Muslim (n = 16), Christian (n = 4), Protestant (n = 3), Catholic (n = 2), Muslim and Hindu (n = 2), Muslim and Christian (n = 1), Muslim and Traditional (n = 1), Evangelical (n = 1), and among those with any affiliation (n = 1). The remaining articles found risk associated with the Muslim (n = 4), Christian (n = 3), ‘Traditional’ (n = 2), or Catholic (n = 1) affiliations.

Of the ten studies reporting both protection and sexual risk as associated with a religious affiliation, five described an association of sexual risk and protection with being Muslim, four with being Christian, and one described protection as associated with Christianity and risk as associated with any affiliation. Of these ten studies, five reported that affiliation was protective in regards to some outcomes but was associated with lower rates of condom use. Among the other five, two found affiliation to be associated with lower prevalence but higher risk, one found the same affiliation to be associated with later sexual initiation and fewer sexual partners but a higher likelihood of paying for sex, and two identified some affiliations to be associated with lower risks and others with higher risks. One study also identified Islam to be associated with a lower prevalence among men but higher prevalence among women (see Table 1).

Religiosity and Sexual HIV Risk (n = 48 Studies)

Articles exploring differences in sexual risk by religiosity without specifying the religious affiliation of the sample were predominantly conducted in the US, with 72.9 % (n = 35) of studies conducted in the US only examining religiosity. Studies with youth or young adults only were also more likely to only consider religiosity (p < .001) and to be conducted in the US (p < .01) when compared to studies with mixed or adult only samples.

Forty-eight papers examined how sexual risk for HIV varied according to religiosity without describing the religious affiliation of the sample. Religiosity was defined in various ways. The most frequently used marker of religiosity was attendance or participation in religious services (n = 28). Other commonly used indicators included the importance of religion in respondent’s lives (n = 11), how religious they were (n = 7), how religion played a role in their upbringing or childhood (n = 4), and the influence of religion on their behavior (n = 4). Other indicators were also common (n = 19), with nine using religiosity scales adapted or obtained from various sources. Two of the nine articles cited the same scale [152]. More than half of the studies in this group included more than one indicator of religiosity (n = 35). A few also reported measuring religion but did not specify the name of the affiliation, or referred to a denomination without specifying that the sample identified with this affiliation.

Sexual HIV risk outcomes analyzed in studies focused on religiosity included condom use (n = 21), having multiple partners (n = 14), sexual initiation (n = 9), a general sexual risk indicator or composite (n = 15), and other outcomes (n = 14), with 20 studies considering multiple of these outcomes. Of those in the ‘other’ category, two included accessing commercial sex, one considered HIV seropositive status, and no studies considered STI status or symptoms.

Findings are reported in Table 2. Most studies found religiosity to be protective, with participants who were more religious experiencing lower levels of sexual risk (n = 30). Another eight studies found religiosity to have no association with risk, five found religiosity to be associated with increased sexual HIV risk, and three cited religiosity as being associated with both an increase and decrease in risk. Of the three that found both risk and protective results, one found religiosity to be associated with risk for some men and protection for women; another found attendance to be associated with abstinence, but among sexually active participants, attendance was associated with lower levels of condom use; and the third found a religious upbringing to be associated with a lower likelihood of sexual initiation as well as lower sexual literacy. Four of the five studies that identified religiosity as a risk factor found religiosity to be associated with lower levels of condom use. Two studies did not fit this framework of religiosity relating to risk or protection: one reported an association between ‘what one’s religion says about gay sex’ and risk behavior [16] and another described increased relevance of religion among participants who had not had sex [17].

Both Religiosity and Affiliation (n = 32 Studies)

Thirty-two studies included measures of both religious affiliation and religiosity. As presented in Table 3, 19 studies presented results regarding participants who were Catholic. An equal number included Muslim (n = 13) and Protestant (n = 13) participants, and nine included Christian participants. Most studies (n = 25) included other categories as well, such as ‘none’ or no religion (n = 10), ‘other’ (n = 9), other Christian denominations (n = 8), Jewish (n = 4), Buddhist (n = 2), ‘African traditional’ (n = 1), and Animist (n = 1).

Religiosity was measured by frequency of attendance or participation in religious services (n = 17), the importance of religion in participants’ lives (n = 8), how religious they considered themselves to be (n = 6), the influence of religion on their behavior (n = 6), and the role of religion in their upbringing (n = 2). Many studies (n = 15) considered other indicators, and 17 included more than one measure of religiosity. Five included different measures used by other researchers.

Sexual risk behaviors considered in these studies included condom use (n = 13), sexual initiation (n = 10), having multiple or extra partners (n = 8), a general sexual risk indicator (n = 4), or another indicator (n = 13). Thirteen studies included more than one indicator.

Most studies in this group described findings related to religiosity (n = 31), and ten also reported differences according to religious affiliation. Religiosity was found to be associated with lower levels of sexual HIV risk in 22 studies, associated with higher risk in three, associated with both increased and decreased risk in one, and was not significant in five studies. Results on the influence of religious affiliation were mixed, with reduced levels of sexual risk associated with being Catholic (n = 2), non-Catholic (n = 2), Christian or Orthodox Christian (n = 2), Muslim (n = 1), and non-Muslim (n = 1). Risk was associated with changing Christian denominations in one study, and in another, having a ‘traditional’ Jewish family background was associated with both risk and protection when compared a secular upbringing (see Table 3).

Differences Across Study Categories

Differences were apparent across the three conceptualizations of religion studied (affiliation only, religiosity only, both affiliation and religiosity). Whether a study considered religious affiliation or religiosity was primarily determined by study region. Studies conducted outside the US examined differences in sexual HIV risk outcomes according to religious affiliation, with nearly three quarters of studies in Africa considering participants only by affiliation, compared to less than 5 % of studies in the US. Alternately, a large group of studies (n = 48), most of which were conducted in the US, explored religiosity without describing the sample’s religious affiliation.

Among all studies that examined religiosity (n = 80), findings varied according to study region, participant age group, and the risk outcome considered. Approximately two thirds of studies reporting results regarding religiosity in Africa (n = 18) and the Americas (n = 46), and all studies in the Western Pacific (n = 7) and the Middle East (n = 2) found higher religiosity to be associated only with reduced sexual risk. Of the five studies reporting religiosity results in Europe, only one found higher religiosity to be associated with reduced risk.

Studies with youth were more likely to measure religiosity only and to be conducted within the US, when compared to studies with mixed or adult only samples. Additionally, studies tended to use different sexual risk outcomes according to participant age. Across the 137 studies, sexual initiation was more likely to be included as a measure of sexual risk among youth and young adult samples (32.1 %, 17 out of 53 studies) when compared to mixed age or adult only samples (14.3 %, 12 out of 84, p < .05).

Over half of the studies that included condom use as an outcome found religiosity to be associated with lower levels of sexual risk (57.6 %, or 19 out of 33) while 71.1 % of studies (32 out of 45) that did not include condom use found religiosity to be protective. This difference was not significant as the .05 level (p = .154). Most studies that found religiosity to be associated only with increased sexual risk examined condom use as an outcome (77.8 %, or 7 out of 9), with six of these studies identifying an association between religiosity and lower rates of condom use, or feelings that condoms are ineffective.

Mechanisms of Sexual HIV Risk

Half of the studies (n = 68) included some description of the mechanisms that link religiosity or religious affiliation to sexual risk. Mechanisms were minimally described, generally without theoretical support. Most commonly, religion and religiosity were described as influencing sexual HIV risk through behavior norms or belief systems related to sexuality and sexual risk (see Table 4). Thirty-five studies described behavioral norms as influencing sexual risk. For example, studies attributed lower rates of sexual risk to an emphasis on premarital virginity or abstinence [18–21], restrictions on alcohol consumption [22, 23], norms of monogamy [24, 25], or to less tolerance of sexual freedom [26]. A few studies that did not find religion to have a protective effect on risk also identified behavioral norms as explaining associations, for example, attributing no association between religion and risk to the promotion of condom use at similar levels across affiliations [27] and citing deterioration in sexual sanctions due to the influx of Christianity (in rural Thailand) [29].

Studies emphasizing the mechanism of belief suggested religion leads to lower levels of sexual risk through decisions to avoid high-risk behaviors [31, 32]. Some studies ascribed risk to disregarding religious beliefs, suggesting that a failure to follow religious teachings led to risky behavior [33], while others pointed to risks of adhering to beliefs, positing that following religious convictions against condom use and planned sexual activity led to unprotected, unplanned sex [34].

Thirteen studies pointed to the role of social organization and social influence. For example, protective effects of religiosity were attributed to social support and connection that comes through participation and interaction in organized religious activities [35–37], fears of disclosing condemned activities [38], high social control [12], or living in an area with less exposure to alcohol and nightclubs [39].

Nine studies cited circumcision as a factor explaining differences or similarities in risk across affiliations; and an additional nine studies described another mechanism, such as communication between partners, gender roles, polygamy, alcohol use, or education.

Discussion

This systematic review suggests that both religiosity and religious affiliation influence sexual HIV risk in various ways. More than 40 % of studies in this review considered religious affiliation but not measures of religiosity. Approximately one third of studies addressed religiosity but did not report affiliation, and half of the studies reviewed did not examine potential mechanisms. Of those that described mechanisms linking religion and sexual HIV risk, major mechanisms identified included (1) behavior norms, (2) beliefs, and (3) social influence.

Results relating to religious affiliation suggest that engagement in sexual risk may vary according to religious affiliation. Protective effects were found most often among groups of people affiliated with Islam, however, most of these studies utilized HIV prevalence or seropositive status as the sexual risk outcome (n = 14), rather than indicating specific sexual risk behaviors. Although this leaves little evidence as to what aspects of religious affiliation may be associated with particular sexual risk behaviors, 35 of the studies that only examined religious affiliation also incorporated discussion on possible mechanisms between affiliation and risk. Most of the studies that found Islam to be protective ascribed this relationship to the role of behavior norms or higher rates of circumcision among Muslim men when compared to those of other affiliations. Studies identifying affiliation to be associated with risks suggested risks resulted from restrictions on behaviors, lower levels of adherence to teachings, traditions influencing the ability of women to avoid risk, and polygamy.

Studies that only measured religious affiliation were predominantly conducted outside of the US. Researchers may be interested in risk outcomes associated with denominations less commonly found in the US. For example, there may be an interest in studying differences between Muslims and Christians in locations where large groups of people identifying with each affiliation reside, such as in Africa. Without attention to other aspects of religion such as levels of participation and adherence, beliefs, and practices, this research provides only a cursory understanding of how religion influences behavior.

Studies only considering religiosity were conducted primarily in the US. Researchers may be less likely to consider religious affiliation in the US if they assume the reader is aware of the sample’s religious affiliation or if they consider affiliation differences to be less relevant in predicting behavior than religiosity. When the sample’s affiliation is not measured or described, study findings are limited. The large number of affiliations present in the US may present difficulties for researchers, but these can be addressed through preliminary screening or utilization of measures conducted with similar groups of people. As the research included in this review suggests affiliation is associated with differences in sexual risk outcomes, it is critical to measure and report affiliation in addition to religiosity.

The lower likelihood of observing religiosity to have a protective effect among studies conducted in Europe may suggest that religiosity is less prevalent, or that it has a weaker effect, in different parts of the world. However, study numbers by location are insufficient to reach conclusions about varying levels of religiosity or religiosity’s impact.

Studies on sexual risk in the US appear to be more narrowly focused on religiosity among younger samples when compared to studies conducted elsewhere that tended to include adult or mixed age samples and measure only affiliation. Additionally, studies conducted among youth and young adults only were more likely to utilize sexual initiation as a measure of risk, as sexual initiation is a less meaningful indicator of sexual risk for populations of adults who are sexually active.

Studies that found religiosity to be associated with higher rates of sexual HIV risk were most likely to conceptualize risk as lower rates of condom use. Although the smaller number of studies that identified a link between religiosity and risk tended to include condom use as the outcome, most studies that considered condom use as an outcome found religiosity to be protective in regards to sexual HIV risk overall. Some of these studies examined multiple outcomes without reporting findings between religiosity and condom use. Others described an association between religion and condom use but did not identify potential mechanisms. Of the studies that discussed mechanisms linking religion and condom use, studies that identified a protective effect pointed to positive social influences resulting from religious leaders, a desire to adhere to social norms, and fears about HIV. Studies identifying religiosity to be associated with risk (lower rates of condom use) pointed to opposition from religious groups towards condom sales as well as beliefs linking sexual behavior to punishment. Although the relationship between religiosity and condom use appears to be context specific, additional reporting of findings and research on this topic is needed to identify common pathways between religious influence and condom use.

A limited number of studies examined mechanisms between religion and sexual risk outcomes. Most often these studies attributed the influence of religion on sexual behavior to religious behavior norms, beliefs, and social support. Behavior norms were most often considered the pathway through which religion influenced sexual risk outcomes, suggesting that belonging to a religious community coincides with social expectations and group influence on sexual norms. Studies citing beliefs suggest that an individual’s appropriation of religious convictions (i.e. regarding monogamy or abstinence) influenced their individual risk behaviors. The emphasis of other studies on social support pointed to the influence of social control, supports and expectations, communication, networks, and fears of social isolation.

Specific religious practices that may form causal pathways between religion and risk were also cited by some studies (particularly those on affiliation only), including circumcision, polygamy, and alcohol use. Other studies pointed to aspects of religiosity such as a sense of spirituality, divine pressures, moral reasoning, or altruism and a concern for others as potentially influencing risk behaviors. Some suggested tradition and societal expectations were more pertinent than religious influence or that the influence of religion was minimal when compared to other cultural influences such as the media.

While the explanations put forward compose a list of mechanisms that could be understood through various theoretical frames relating to gender and power, social capital, and decision making, additional research is needed to demonstrate pathways through which religion influences risk. Adamczyk and Hayes [40] explored differences in premarital and extramarital sex across religious affiliation in multiple countries and found that the lower rate of premarital sex among married Hindus and Muslims was not explained by an earlier marriage age. Furthermore, lower rates of extramarital sex among nations with a higher percentage of Muslims were not explained by restrictions on female mobility. Conducting in depth analysis of HIV and religion in Africa, Trinitapoli and Weinreb [151] explore mechanisms between religious affiliation, religiosity, and sexual HIV risks, suggesting (1) abstinence is more common among people who attend religious services more regularly and is primarily explained through attitudes about acceptable sexual behavior, but does not vary by affiliation; (2) monogamy varies by affiliation, is more likely among those who attend regularly, and can be explained by the mechanism of social control or monitoring from religious leaders; and (3) condom use is not strongly effected by affiliation, and religiosity does not impact condom use or attitudes towards condoms. They did find, however, that positive religious leader attitudes towards condoms coincided with higher levels of condom use among adherents. Additional research that considers individual and community level religious influences could help disentangle ways in which religion impacts sexual risk in various contexts.

Implications for Future Research

Future research on religion and sexual HIV risk needs to: (1) incorporate measures of both religious affiliation and religiosity; (2) consider specific sexual risk outcomes in addition to HIV prevalence; (3) determine which measures of religiosity are most relevant to understanding sexual risk contexts for particular groups of people; (4) more thoroughly examine mechanisms by which religion may influence sexual risk behaviors; and (5) conduct qualitative research to further examine how religious affiliation and religiosity are linked to specific sexual risk behaviors.

References

Cotton S, Zebracki K, Rosenthal SL, Tsevat J, Drotar D. Religion/spirituality and adolescent health outcomes: a review. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(4):472–80.

Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(6):700–20.

Rew L, Wong YJ. A systematic review of associations among religiosity/spirituality and adolescent health attitudes and behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(4):433–42.

Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–75.

Balogun AS. Islamic perspectives on HIV/AIDS and antiretroviral treatment: the case of Nigeria. Afr J AIDS Res. 2010;9(4):459–66.

Monshipouri M, Trapp T. HIV/AIDS, religion, and human rights: a comparative analysis of Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Iran. Hum Rights Rev. 2012;13(2):187–204.

Francesca E. AIDS in contemporary Islamic ethical literature. Med Law. 2002;21(2):381–94.

Obermeyer CM. HIV in the Middle East. Br Med J. 2006;333(7573):851–4.

Cotton S, Puchalski CM, Sherman SN, Mrus JM, Peterman AH, Feinberg J, et al. Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(S5):S5–13.

Pargament K, McCarthy S, Shah P, Ano G, Tarakeshwar N, Wachholtz A, et al. Religion and HIV: a review of the literature and clinical implications. South Med J (Birmingham, Ala.). 2004;97(12):1201.

Gray PB. HIV and Islam: is HIV prevalence lower among Muslims? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(9):1751–6.

Velayati A, Bakayev V, Bahadori M, Tabatabaei S, Alaei A, Farahbood A, et al. Religious and cultural traits in HIV/AIDS epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10(4):486–97.

Parker RG, Easton D, Klein CH. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. AIDS. 2000;14:S22–32.

Organista KC, Carrillo H, Ayala G. HIV prevention with Mexican migrants: review, critique, and recommendations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:S227–39.

Wingood GM, Simpson-Robinson L, Braxton ND, Raiford JL. Design of a faith-based HIV intervention successful collaboration between a university and a church. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(6):823–31.

Ross MW, Henry D, Freeman A, Caughy M, Dawson AG Jr. Environmental influences on safer sex in young gay men: a situational presentation approach to measuring influences on sexual health. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33(3):249–57.

Paradise JE, Cote J, Minsky S, Lourenco A, Howland J. Personal values and sexual decision-making among virginal and sexually experienced urban adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(5):404–9.

Mberu BU, White MJ. Internal migration and health: premarital sexual initiation in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(8):1284–93.

Koffi AK, Kawahara K. Sexual abstinence behavior among never-married youths in a generalized HIV epidemic country: evidence from the 2005 Côte d’Ivoire AIDS indicator survey. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):408.

Obiaja KC, Darrow WW, Sánchez-Braña E, Uribe CL. Self-assessed spirituality, worship attendance, and HIV-related preventive behaviors among unmarried ethnic minority adults living in a high AIDS prevalence area. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2008;7(4):399–415.

Gilbert SS. The influence of Islam on AIDS prevention among Senegalese university students. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(5):399–407.

Alavi SM, Soltani MH. Study of urethritis among subjects regardless to religious rites. Pak J Med Sci Oct-Dec. 2010;26(4):946–9.

Mbulaiteye S, Ruberantwari A, Nakiyingi J, Carpenter L, Kamali A, Whitworth J. Alcohol and HIV: a study among sexually active adults in rural southwest Uganda. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(5):911–5.

Campbell C, Williams B, Gilgen D. Is social capital a useful conceptual tool for exploring community level influences on HIV infection? An exploratory case study from South Africa. AIDS Care. 2002;14(1):41–54.

Noden BH, Gomes A, Ferreira A. AIDS-related knowledge and sexual behaviour among married and previously married persons in rural central Mozambique. J Soc Asp HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2009;6(3):134–44.

Nattrass N. Poverty, sex and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):833–40.

Muula AS, Thomas JC, Pettifor AE, Strauss RP, Suchindran CM, Meshnick SR. Religion, condom use acceptability and use within marriage among rural women in Malawi. World Health Popul. 2011;12(4):35–47.

Scorgie F, Smit JA, Kunene B, Martin-Hilber A, Beksinska M, Chersich MF. Predictors of vaginal practices for sex and hygiene in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: findings of a household survey and qualitative inquiry. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(04):381–98.

Kobori E, Visrutaratna S, Kada A, Wongchai S, Ono-Kihara M, Kihara M. Prevalence and correlates of sexual behaviors among Karen villagers in northern Thailand. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(4):611–8.

Ehon A. Assessing sexual communication and condom negotiation among university undergraduate students in sexual relationship; in the era of HIV/AIDS. IFE PsychologIA. 2008;16(2):188–209.

Coleman CL, Ball K. Predictors of self-efficacy to use condoms among seropositive middle-aged African American men. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31(7):889–904.

Shirazi KK, Morowatisharifabad MA. Religiosity and determinants of safe sex in Iranian non-medical male students. J Relig Health. 2009;48(1):29–36.

Isiugo-Abanihe UC. Extramarital relations and perceptions of HIV/AIDS in Nigeria. Health Transit Rev. 1994;4(2):111–25.

Koniak-Griffin D, Lesser J, Uman G, Nyamathi A. Teen pregnancy, motherhood, and unprotected sexual activity. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26(1):4–19.

Dowshen N, Forke CM, Johnson AK, Kuhns LM, Rubin D, Garofalo R. Religiosity as a protective factor against HIV risk among young transgender women. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(4):410–4.

Margolis AD, MacGowan RJ, Grinstead O, Sosman J, Kashif I, Flanigan TP. Unprotected sex with multiple partners: implications for HIV prevention among young men with a history of incarceration. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):175–80.

Tung W, Lu M, Cook DM. Condom use and stages of change among college students in Taiwan. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27(6):474–81.

Udell W, Donenberg G, Emerson E. The impact of mental health problems and religiosity on African-American girls’ HIV-risk. Cult Divers Ethni Minor Psychol. 2011;17(2):217.

Nishimura Y, Ono-Kihara M, Mohith J, NgManSun R, Homma T, DiClemente R, et al. Sexual behaviors and their correlates among young people in Mauritius: a cross-sectional study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2007;7(1):8.

Adamczyk A, Hayes BE. Religion and sexual behaviors: understanding the influence of Islamic cultures and religious affiliation for explaining sex outside of marriage. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(5):723–46.

Oyediran KA, Feyisetan OI, Akpan T. Predictors of condom-use among young never-married males in Nigeria. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(3):273.

Banandur P, Rajaram SP, Mahagaonkar SB, Bradley J, Ramesh BM, Washington RG, et al. Heterogeneity of the HIV epidemic in the general population of Karnataka state, south India. BMC Public Health 2011;11(Suppl 6):S13.

Hunter LM, Reid-Hresko J, Dickinson TW. Environmental change, risky sexual behavior, and the HIV/AIDS pandemic: linkages through livelihoods in rural Haiti. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2011;30(5):729–50.

James CA, Hart TA, Roberts KE, Ghai A, Petrovic B, Lima MD. Religion versus ethnicity as predictors of unprotected vaginal intercourse among young adults. Sexual Health. 2011;8(3):363–71.

Dubois-Arber F, Meystre-Agustoni G, Jeannin A, De Heller K, Pécoud A, Bodenmann P. Sexual behaviour of men that consulted in medical outpatient clinics in Western Switzerland from 2005–2006: risk levels unknown to doctors? BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):528.

Wand H, Ramjee G. Targeting the hotspots: investigating spatial and demographic variations in HIV infection in small communities in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(1):41.

Noden BH, Gomes A, Ferreira A. Influence of religious affiliation and education on HIV knowledge and HIV-related sexual behaviors among unmarried youth in rural central Mozambique. AIDS Care. 2010;22(10):1285–94.

Maticka-Tyndale E, Tenkorang EY. A multi-level model of condom use among male and female upper primary school students in Nyanza, Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(3):616–25.

Gyimah SO, Tenkorang EY, Takyi BK, Adjei J, Fosu G. Religion, HIV/AIDS and sexual risk-taking among men in Ghana. J Biosoc Sci. 2010;42(4):531.

Sambisa W, Curtis SL, Stokes CS. Ethnic differences in sexual behaviour among unmarried adolescents and young adults in Zimbabwe. J Biosoc Sci. 2010;42(1):1.

Lazarus J, Moghaddassi M, Godeau E, Ross J, Vignes C, Östergren P, et al. A multilevel analysis of condom use among adolescents in the European Union. Public Health. 2009;123(2):138–44.

Thomas B, Mimiaga MJ, Menon S, Chandrasekaran V, Murugesan P, Swaminathan S, et al. Unseen and unheard: predictors of sexual risk behavior and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Chennai, India. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(4):372–83.

Hubbard J, Rogers RL. Cultural factors influencing HIV-related attitudes and behaviors in the third world: ethnicity and religion in Guyana. Race/Ethn Multidiscip Glob Contexts. 2009;3(1):97–114.

Frank S, Esterhuizen T, Jinabhai C, Sullivan K, Taylor M. Risky sexual behaviours of high-school pupils in an era of HIV and AIDS. S Afr Med J. 2008;98(5):394–8.

Gerber TP, Berman D. Heterogeneous condom use in contemporary Russia. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39(1):1–17.

Carter MW, Kraft JM, Koppenhaver T, Galavotti C, Roels TH, Kilmarx PH, et al. “A bull cannot be contained in a single kraal”: concurrent sexual partnerships in Botswana. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6):822–30.

Hallett TB, Lewis JJ, Lopman BA, Nyamukapa CA, Mushati P, Wambe M, et al. Age at first sex and HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Stud Fam Plann. 2007;38(1):1–10.

Talukdar A, Khandokar MR, Bandopadhyay SK, Detels R. Risk of HIV infection but not other sexually transmitted diseases is lower among homeless Muslim men in Kolkata. AIDS. 2007;21(16):2231.

Soldan VAP, Bisika T, Tsiu A. Social, economic and demographic determinants of sexual risk behaviors among men in rural Malawi: a district-level study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;11(2):33–46.

Lawal RA, Adeyemi JD, Akinhanmi AA, Haruna AA, Bassey LB, Coker RO, et al. A rapid situation assessment of sexual risk behaviour of alcohol users in Lagos, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2007;14(3):180–9.

Agha S, Hutchinson P, Kusanthan T. The effects of religious affiliation on sexual initiation and condom use in Zambia. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(5):550–5.

Drain PK, Halperin DT, Hughes JP, Klausner JD, Bailey RC. Male circumcision, religion, and infectious diseases: an ecologic analysis of 118 developing countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6(1):172.

Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS, Mbu RE, Nana P, Kouam L. Wealth and sexual behaviour among men in Cameroon. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2006;6(1):11.

Mitsunaga TM, Powell AM, Heard NJ, Larsen UM. Extramarital sex among Nigerian men: polygyny and other risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(4):478–88.

Langeni T. Male circumcision and sexually transmitted infections in Botswana. J Biosoc Sci. 2005;37(1):75–88.

Mekonnen Y, Sanders E, Messele T, Wolday D, Dorigo-Zestma W, Schaap A, et al. Prevalence and incidence of, and risk factors for, HIV-1 infection among factory workers in Ethiopia, 1997–2001. J Health Popul Nutr. 2005;23(4):358–68.

Lagarde E, Enel C, Seck K, Gueye-Ndiaye A, Piau J, Pison G, et al. Religion and protective behaviours towards AIDS in rural Senegal. AIDS. 2000;14(13):2027–33.

Hill ZE, Cleland J, Ali MM. Religious affiliation and extramarital sex among men in Brazil. Int Family Plan Perspect. 2004;30(1):20–6.

Takyi BK. Religion and women’s health in Ghana: insights into HIV/AIDS preventive and protective behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(6):1221–34.

Abebe Y, Schaap A, Mamo G, Negussie A, Darimo B, Wolday D, et al. HIV prevalence in 72,000 urban and rural male army recruits, Ethiopia, 1999–2000. Ethiop Med J. 2003;41(Suppl 1):25–30.

Kapiga SH, Lugalla J. Sexual behaviour patterns and condom use in Tanzania: results from the 1996 Demographic and Health Survey. AIDS Care. 2002;14(4):455–69.

Hawken MP, Melis RD, Ngombo DT, Mandaliya KN, Ng’ang’a LW, Price J, et al. Opportunity for prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in Kenyan youth: results of a population-based survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(5):529–35.

Todd J, Munguti K, Grosskurth H, Mngara J, Changalucha J, Mayaud P, et al. Risk factors for active syphilis and TPHA seroconversion in a rural African population. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77(1):37–45.

Takyi BK. Correlates of HIV/AIDS-related knowledge and preventive behavior of men in Africa. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2001;24(2):234–57.

Bailey RC, Neema S, Othieno R. Sexual behaviors and other HIV risk factors in circumcised and uncircumcised men in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;22(3):294.

Rakwar J, Lavreys L, Thompson ML, Jackson D, Bwayo J, Hassanali S, et al. Cofactors for the acquisition of HIV-1 among heterosexual men: prospective cohort study of trucking company workers in Kenya. AIDS. 1999;13(5):607–14.

Lugoe W, Klepp K, Skutle A. Sexual debut and predictors of condom use among secondary school students in Arusha, Tanzania. AIDS Care. 1996;8(4):443–52.

Cooksey EC, Rindfuss RR, Guilkey DK. The initiation of adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior during changing times. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37(1):59–74.

Mnyika KS, Klepp K, Kvåle G, Ole-King’ori N. Risk factors for HIV-1 infection among women in the Arusha region of Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1996;11(5):484–91.

Buga GA, Amoko DH, Ncayiyana DJ. Adolescent sexual behaviour, knowledge and attitudes to sexuality among school girls in Transkei, South Africa. East Afr Med J. 1996;73(2):95.

Shabbir I, Larson C. Urban to rural routes of HIV infection spread in Ethiopia. J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;98(5):338.

Nunn AJ, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Malamba SS, Seeley JA, Mulder DW. Risk factors for HIV-1 infection in adults in a rural Ugandan community: a population study. AIDS. 1994;8(1):81–6.

Malamba SS, Wagner H, Maude G, Okongo M, Nunn AJ, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, et al. Risk factors for HIV-1 infection in adults in a rural Ugandan community: a case-control study. AIDS. 1994;8(2):253–8.

Duncan ME, Roggen E, Tibaux G, Pelzer A, Mehari L, Piot P. Seroepidemiological studies of Haemophilus ducreyi infection in Ethiopian women. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21(5):280–8.

Flaskerud JH, Nyamathi AM. Effects of an AIDS education program on the knowledge, attitudes and practices of low income black and Latina women. J Commun Health. 1990;15(6):343–55.

Štulhofer A, Šoh D, Jelaska N, Baćak V, Landripet I. Religiosity and sexual risk behavior among Croatian college students, 1998–2008. J Sex Res. 2011;48(4):360–71.

Boyd-Starke K, Hill OW, Fife J, Whittington M. Religiosity and HIV risk behaviors in African-American students. Psychol Rep. 2011;108(2):528–36.

Wutoh AK, Nichols English G, Daniel M, Kendall KA, Cobran EK, Clarke Tasker V, et al. Pilot study to assess HIV knowledge, spirituality, and risk behaviors among older African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(3):265–8.

Voetsch AC, Thomas PE, Satcher Johnson A, Millett GA, Mundey L, Goode C, et al. Sex with bisexual men among Black female students at historically Black colleges and universities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1198.

Golub SA, Ja’Nina JW, Longmire-Avital B, Bimbi DS, Parsons JT. The role of religiosity, social support, and stress-related growth in protecting against HIV risk among transgender women. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(8):1135–44.

Agardh A, Emmelin M, Muriisa R, Östergren P. Social capital and sexual behavior among Ugandan university students. Glob Health Action. 2010;3:1–13.

Wagner GJ, Holloway I, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Ryan G, Kityo C, Mugyenyi P. Factors associated with condom use among HIV clients in stable relationships with partners at varying risk for HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1055–65.

Washington TA, Wang Y, Browne D. Difference in condom use among sexually active males at historically black colleges and universities. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57(4):411–8.

Bakare MO, Agomoh AO, Ebigbo PO, Onyeama GM, Eaton J, Onwukwe JU, et al. Co-morbid disorders and sexual risk behavior in Nigerian adolescents with bipolar disorder. Int Arch Med. 2009;2(1):1–5.

Štulhofer A, Graham C, Božičević I, Kufrin K, Ajduković D. An assessment of HIV/STI vulnerability and related sexual risk-taking in a nationally representative sample of young Croatian adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38(2):209–25.

Voisin DR, Neilands TB, Salazar LF, Crosby R, DiClemente RJ. Pathways to drug and sexual risk behaviors among detained adolescents. Soc Work Res. 2008;32(3):147–57.

Weiss ML, Chitwood DD, Sánchez J. Religiosity, drug use, and HIV-related risk behaviors among heroin injectors. J Drug Issue. 2008;38(3):883–909.

Nnedu ON, McCorvey S, Campbell-Forrester S, Chang J, Salihu HM, Jolly PE. Factors influencing condom use among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Montego Bay, Jamaica. Open Reprod Sci J. 2008;1(1):45–50.

Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Ronis DL. Predicting condom use among sexually experienced Latino adolescents. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29(6):724–38.

Broman CL. Sexual risk behavior among black adolescents. J Afr Am Stud. 2007;11(3–4):180–8.

Lewis LJ, Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E. Developmental, ethnic, and social influences on participation in sexual possibility situations for youth with HIV-positive and HIV-negative mothers. J Early Adolesc. 2006;26(2):160–85.

Dodge B, Sandfort TG, Yarber WL, de Wit J. Sexual health among male college students in the United States and the Netherlands. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(2):172.

Raffaelli M, Zamboanga BL, Carlo G. Acculturation status and sexuality among female Cuban American college students. J Am Coll Health. 2005;54(1):7–13.

Elifson KW, Klein H, Sterk CE. Religiosity and HIV risk behavior involvement among “at risk” women. J Relig Health. 2003;42(1):47–66.

Wayment HA, Wyatt GE, Tucker MB, Romero GJ, Carmona JV, Newcomb M, et al. Predictors of risky and precautionary sexual behaviors among single and married white women. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;33(4):791–816.

Avants SK, Marcotte D, Arnold R, Margolin A. Spiritual beliefs, world assumptions, and HIV risk behavior among heroin and cocaine users. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(2):159.

Bachanas PJ, Morris MK, Lewis-Gess JK, Sarett-Cuasay EJ, Flores AL, Sirl KS, et al. Psychological adjustment, substance use, HIV knowledge, and risky sexual behavior in at-risk minority females: developmental differences during adolescence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(4):373–84.

Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB III, Villarruel AM. Predicting intentions and condom use among Latino college students. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2002;13(2):59–69.

Fierros-Gonzalez R, Brown JM. High risk behaviors in a sample of Mexican-American college students. Psychol Rep. 2002;90(1):117–30.

Abdullah AS, Fielding R, Hedley AJ, Luk YK. Risk factors for sexually transmitted diseases and casual sex among Chinese patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in Hong Kong. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(6):360–5.

Braithwaite K, Thomas VG. HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and risk-behaviors among African-American and Caribbean college women. Int J Adv Couns. 2001;23(2):115–29.

Langer LM, Warheit GJ, Mcdonald LP. Correlates and predictors of risky sexual practices among a multi-racial/ethnic sample of university students. Soc Behav Personal. 2001;29(2):133–44.

Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, Clark LF. Reconceptualizing adolescent sexual behavior: beyond did they or didn’t they? Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32(3):111–7.

Paul C, Fitzjohn J, Herbison P, Dickson N. The determinants of sexual intercourse before age 16. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(2):136–47.

Simeon DT, LeFranc E, Bain B, Wyatt GE. Experiences and socialization of Jamaican men with multiple sex partners. West Indian Med J. 1999;48(4):212–5.

Hines AM, Snowden LR, Graves KL. Acculturation, alcohol consumption and AIDS-related risky sexual behavior among African American women. Women Health. 1998;27(3):17–35.

Lugoe WL, Biswalo PM. Self-restraining and condom use behaviours: the HIV/AIDS prevention challenges in Tanzanian schools. Int J Adolesc Youth. 1997;7(1):67–81.

Reitman D, St Lawrence JS, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E. Predictors of African American adolescents’ condom use and HIV risk behavior. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8(6):499–515.

Lugoe W, Klepp K, Rise J, Skutle A, Biswalo P. Relationship between sexual experience and non-sexual behaviours among secondary school students in Arusha, Tanzania. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(10):635–40.

Neff JA, Burge SK. Alcohol use, liberal/conservative orientations, and ethnicity as predictors of sexual behaviors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;8(3):302–12.

Caetano R, Hines AM. Alcohol, sexual practices, and risk of AIDS among blacks, Hispanics, and whites. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;10(5):554–61.

Murstein BI, Mercy T. Sex, drugs, relationships, contraception, and fears of disease on a college campus over 17 years. Adolescence. 1994;29(114):303–22.

Dunne MP, Edwards R, Lucke J, Donald M, Raphael B. Religiosity, sexual intercourse and condom use among university students. Aust J Public Health. 1994;18(3):339–41.

Seidman SN, Mosher WD, Aral SO. Predictors of high-risk behavior in unmarried American women: adolescent environment as risk factor. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15(2):126–32.

Langer LM, Zimmerman RS, McNeal R. Explaining the association of race and ethnicity with the HIV/AIDS-related attitudes, behaviors and skills of high school students. Popul Res Policy Rev. 1992;11(3):233–47.

Baldwin JD, Baldwin JI. Factors affecting AIDS-related sexual risk-taking behavior among college students. J Sex Res. 1988;25(2):181–96.

Feldman BS, Shtarkshall RA, Ankol OE, Sela T, Kark JD. Diminishing gender differences in condom use among a national sample of young Israeli men and women between 1993 and 2005. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(3):311–4.

Muula AS. Marriage, not religion, is associated with HIV infection among women in rural Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):125–31.

RF Gillum MD M. Associations between religious involvement and behavioral risk factors for HIV/AIDS in American women and men in a national health survey. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(3):284–293.

Aniebue P, Aniebue U. HIV/AIDS-related knowledge, sexual practices and predictors of condom use among long-distance truck drivers in Nigeria. South Afr J HIV Med. 2009;10(2):54.

Kabiru CW, Orpinas P. Factors associated with sexual activity among high-school students in Nairobi, Kenya. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):1023–39.

Shtarkshall RA, Carmel S, Jaffe-Hirschfield D, Woloski-Wruble A. Sexual milestones and factors associated with coitus initiation among Israeli high school students. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38(4):591–604.

Tavares CM, Schor N, França Junior I, Diniz SG. Factors associated with sexual initiation and condom use among adolescents on Santiago Island, Cape Verde, West Africa. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2009;25(9):1969–80.

Trinitapoli J. Religious teachings and influences on the ABCs of HIV prevention in Malawi. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):199.

Belza MJ, de la Fuente L, Suárez M, Vallejo F, García M, López M, et al. Men who pay for sex in Spain and condom use: prevalence and correlates in a representative sample of the general population. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(3):207–11.

Cerqueira-Santos E, Koller SS, Wilcox B. Condom use, contraceptive methods, and religiosity among youths of low socioeconomic level. Span J Psychol. 2008;11(1):94–102.

Iyaniwura C, Mautin G. Sexual activity and other related practices among youth corpers in Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2008;27(1):13–9.

Manji A, Pena R, Dubrow R. Sex, condoms, gender roles, and HIV transmission knowledge among adolescents in Leon, Nicaragua: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):989–95.

Galvan FH, Collins RL, Kanouse DE, Pantoja P, Golinelli D. Religiosity, denominational affiliation, and sexual behaviors among people with HIV in the United States. J Sex Res. 2007;44(1):49–58.

Odimegwu C. Influence of religion on adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviour among Nigerian university students: affiliation or commitment? Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9(2):125–40.

Hasnain M, Sinacore J, Mensah E, Levy J. Influence of religiosity on HIV risk behaviors in active injection drug users. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):892–901.

Lefkowitz ES, Gillen MM, Shearer CL, Boone TL. Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. J Sex Res. 2004;41(2):150–9.

Allain J, Anokwa M, Casbard A, Owusu-Ofori S, Dennis-Antwi J. Sociology and behaviour of West African blood donors: the impact of religion on human immunodeficiency virus infection. Vox Sang. 2004;87(4):233–40.

McCree DH, Wingood GM, DiClemente R, Davies S, Harrington KF. Religiosity and risky sexual behavior in African-American adolescent females. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(1):2–8.

Miller L, Gur M. Religiousness and sexual responsibility in adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(5):401–6.

Grunseit AC, Richters J. Age at first intercourse in an Australian national sample of technical college students. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(1):11–6.

Shapiro J, Radecki S, Charchian AS, Josephson V. Sexual behavior and AIDS-related knowledge among community college students in Orange County, California. J Community Health. 1999;24(1):29–43.

Davis P, Lay-Yee R. Early sex and its behavioral consequences in New Zealand. J Sex Res. 1999;36(2):135–44.

Lacson RS, Theocharis TR, Strack R, Sy FS, Vincent ML, Osteria TS, et al. Correlates of sexual abstinence among urban university students in the Philippines. Int Family Plan Perspect. 1997;23(4):168–72.

Anderson JE, McCormick L, Fichtner R. Factors associated with self-reported STDs: data from a national survey. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21(6):303–8.

Trinitapoli J, Weinreb A. Religion & AIDS in Africa. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychol Addict Behav. 1996;10(2):90–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shaw, S.A., El-Bassel, N. The Influence of Religion on Sexual HIV Risk. AIDS Behav 18, 1569–1594 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0714-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0714-2