Every day, hundreds of people walk over a portrait of Virginia Woolf, most of them unaware of it. She is depicted, very recognisably, on the floor of the vestibule of the National Gallery, in a mosaic by Boris Anrep of 1933. As one of the muses (Clio, muse of history), she is seen in profile being awakened by Apollo (Osbert Sitwell) and Bacchus (Clive Bell) among other portraits that include Lydia Lopokova and Greta Garbo as assorted muses. But, with her customary aversion to publicity, Woolf was irritated that, in a newspaper report, Anrep had identified the models for his gods and goddesses. This aversion was part and parcel of her attitude towards being painted, sculpted and professionally photographed.

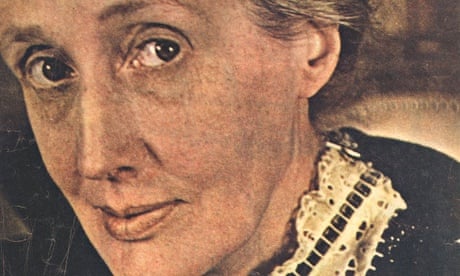

Frances Partridge once remarked that in many photographs Woolf had the look of someone who "had been gravely mad", a look she recognised from patients she had observed at Broadmoor. There was something slightly "wrong", particularly in the formal photographs, with the set of her features. Woolf may well have recognised this and disliked "seeing herself". But with her growing fame from the mid-1920s onwards, demands for photographs and interviews increased. Of the latter she gave none; she provided a few facts only to Winifred Holtby, who was writing a book about Woolf's novels, but refused to meet her; her books (of which she and her husband Leonard Woolf were the publishers at the Hogarth Press) bore no biographical blurbs on their jackets; and most of her obituaries in 1941 contained mistakes or gaps. As far as is known, only once did she appear in a newspaper photograph, which was taken at a public occasion when she was awarded the Femina Vie Heureuse prize for To the Lighthouse.

Woolf's self-consciousness about her appearance had several manifestations. Most acutely, putting on new clothes to go out to dinner or a party caused her almost as much terror as publishing a new book. Shopping in John Lewis, she is assailed by her "dress mania" and feels horribly different from her smart and confident fellow-shoppers. While many of her friends remembered her beauty and physical distinction, they also commented on her almost girlish awkwardness in company and that she was only really relaxed with her family and close friends. Fortunately, some of the best photographs of her are snapshots by Leonard or her sister Vanessa Bell. Professional photographs were another matter.

There is the famous series of Virginia Stephen by GC Beresford taken in July 1902 when she was 20. The beauty inherited from her mother Julia is there for all to see but is now perhaps qualified by what we know was to come, especially the changes wrought on her features by the terrible period of insanity of 1913-15, during which, at one point, four nurses tended her and she was scarcely aware that her first novel had been published. The outline of this beauty remained but, as Leonard commented, it was "painful" to see.

She was equally daunted by sitting for artists. Duncan Grant, who painted her as Virginia Stephen in 1911, told me that he knew he had to work swiftly "or she might just get up and walk out". Indeed, it seems she did just that, for his work is visibly unfinished and almost certainly made in one sitting. Nevertheless, he catches something of her intensely observant presence, if not the more obvious aspects of her beauty. A year or so later, her sister painted her on four occasions, all small in scale and informal in pose – only one depicts her facial features in any conventional sense. Although at that time Bell made several "portraits" in which the faces are virtually blank – post-impressionism at its most minimalist – it is significant that three of the paintings of her sister share this characteristic. Yet on one of Virginia seated in a deckchair, Leonard remarked: "It is more like Virginia in its way than anything else of her." I think he meant by this that the relaxed posture and ruminative effect were entirely typical of his wife.

Undoubtedly, her acute self-consciousness nearly led to disaster when she reluctantly agreed to sit for the young sculptor Stephen Tomlin in the summer of 1931. He was known to her and many of her friends, and was married to the writer Julia Strachey: she was thus on familiar territory. Six sittings were envisaged but after the fourth she struck. It had become an agony to her, already in a highly agitated state after the final rewriting of her most demanding novel The Waves. She hated the sculptor's scrutiny of her head from all angles and, after being persuaded to sit twice more, abandoned the project. Nevertheless, like the Grant portrait, the resulting head-and-shoulders captures something essential about her, aloof and yet alert, with eyes blank yet curiously mobile, the lips just parted as though some volley of brilliant talk is about to happen.

As Woolf's fame increased, she was frequently asked to sit for professional photographers, especially at the behest of American publishers. She refused a good many and would rely on Leonard to take photographs of her or send out comparatively old images. But there is one rather different series (not published until many years after her death), which perhaps brings her to life more than anything else. These photographs were taken by Lady Ottoline Morrell when Woolf was her guest at Garsington Manor in June 1926. They picture Woolf standing, reading or seated talking to fellow guests, some show her with spectacles and cigarette, all taken in a short space of time – pensive, laughing, searching for a phrase. They are the nearest we have to a "movie" of Woolf (she was never filmed and there is only one, unreliable, recording, a few minutes long, of her voice).

At the other end of the scale are two sequences from the 1930s by well-known photographers – the American Man Ray and the German-born Gisèle Freund. It is not known if Woolf was familiar with Ray's work before she agreed to a sitting in London in 1934. She had been introduced to him by the American designer McKnight Kauffer at the private view of a show of Ray's photographs in the offices of the publisher Lund Humphries in Bedford Square. Ray knew little of Woolf and had not read her, but the results were dramatically successful. He applied some lipstick to counterbalance the indoor glare (she apparently never used cosmetics), and for one of the images posed her with arms leaning on a highly contemporary chair back. Here is Woolf, the modern writer. Ray was paid by Harper's Bazaar for the prints, but they were not reproduced until 1937 when The Years was a spectacular and unexpected bestseller in the US.

Freund's images, taken just before the outbreak of war in 1939, are extremely valuable, for not only are they unique in showing Woolf in her London home, but they are in colour. Freund pioneered colour photography and made portraits of James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Aldous Huxley and many other writers.

Freund was twice refused admission to Tavistock Square but eventually Woolf succumbed. She agreed to change her clothes to see which best suited the colour harmony and insisted on being photographed with Leonard (and their spaniel Pinka). In some of the prints, Woolf is pale and lined, in others smiling a little and more youthful. The background of fabrics and mural panels by Bell and Grant adds to the value of the images; this was the inner sanctum of the queen of Bloomsbury where parties were given and friends came to tea. Just over a year later the house was destroyed in the blitz but, for some time, mural panels were left hanging on the wall, open to the weather, as recorded later by the Woolfs' friends Stephen Spender and William Plomer, as the last vestiges of a disappearing world.

Images can tell us only so much, inflected as they are by the photographer's requirements, whims and style. Beresford's group was commissioned but as a family record. Ottoline Morrell's sequence is the closest we have to Woolf as a social being. Man Ray's were a purely commercial transaction. Freund's series is a rewarding mixture of the subject as celebrity and domestic information. The "granite and rainbow" of Woolf's personality will always elude us – we can read what we wish into all these images but perhaps can never say, as Woolf writes of Clarissa Dalloway in the final line of Mrs Dalloway: "For there she was."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion