/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/35309646/483124789.0.jpg)

The Wall Street Journal just published an amazing essay from Taylor Swift, in which she argues that the music industry is not dying, but in fact "just coming alive."

Based on this piece, there are many reasons to believe that Taylor Swift has not been paying very much attention to the music industry.

Taylor Swift doesn't know how people value music

Taylor says that in her opinion, "the value of an album is, and will continue to be, based on the amount of heart and soul an artist has bled into a body of work, and the financial value that artists (and their labels) place on their music when it goes out into the marketplace." This means she thinks artists should make high upfront investments in their albums, and then set correspondingly high prices on them at retail. It's a bet that music consumers will reward quality.

This might make sense if you're Taylor Swift and your enormous army of fans will pre-order anything you tell them to, but the most important lesson of the internet music revolution is that the vast majority of consumers actually reward convenience. That's why the iPod was a huge hit even though digitally-compressed music sounded terrible at the time, and it's why teenagers today get most of their music on YouTube, even though YouTube sounds worse still. It's also why the album is dead: you can't sell a handful of singles and some okayish filler songs to people for $10 or $15 or $25 anymore, because convenient internet music distribution has utterly destroyed the need to bundle everything together. You can just Google the singles and listen to them for free.

This isn't news to the music industry: according to Nielsen numbers released just a few days ago, album sales just keep tanking. Only five records have sold over 500,000 copies so far in 2014, compared to 11 this time in 2013. (The notable exception is the Frozen soundtrack, which has sold 2.7 million copies so far; the next highest seller is Beyoncé's self-titled album is at 702,000.) That's why the industry has has increasingly moved to so-called 360 deals that place far less emphasis on an artist's album sales in favor of taking a cut from touring, merchandise, and licensing. It's also why subscription services like Spotify are probably the future of the industry, and why Apple just spent $3 billion to buy Beats mostly for its streaming service, not its headphones line.

I saw Beats co-founder and former Interscope Records chairman Jimmy Iovine speak in June just after he sold the company to Apple, and he bemoaned the fact that artists are churning out bad-sounding singles while touring instead of spending years in the studio crafting Led Zeppelin-like masterpieces. "It's a simple problem," he said, describing his efforts to find new revenue models with Beats and now at Apple. "The album is going away." Cranking out singles while on the road makes perfect economic sense right now: touring is one of the few music industry activities that still makes money, and recording songs quickly reduces the upfront investment needed in a product that no longer generates a ton of revenue at retail. Here, just watch Jimmy say it himself.

Taylor Swift does not understand that the internet killed scarcity

Taylor makes a nice little argument in favor of paying for music. "Music is art," she says, "and art is important and rare. Important, rare things are valuable. Valuable things should be paid for. It's my opinion that music should not be free, and my prediction is that individual artists and their labels will someday decide what an album's price point is."

This is an impressively-constructed syllogism. It is also deeply, deeply wrong.

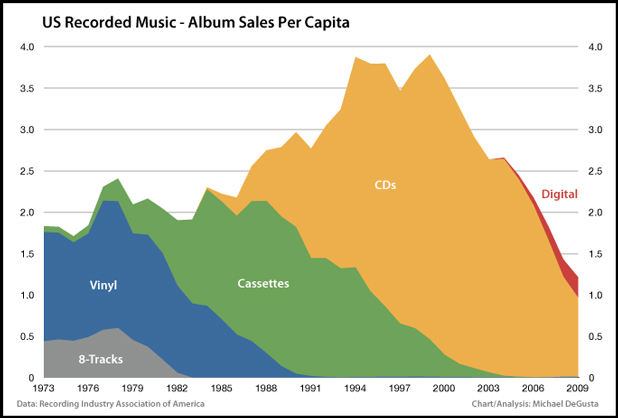

The single hardest economic problem posed by the internet is the end of scarcity. Even just 10 years ago, most people experienced a one-to-one relationship between creative works and the physical objects they were delivered on: your music came on CDs, your movies came on DVDs, and your news came on printed magazines and newspapers. Since there's a scarce number of these objects in the world, it's easy to buy and sell them, because their prices will follow the laws of supply and demand: limited-edition vinyl records will be more expensive than regular CDs, because there are simply fewer of them. If you wanted a CD full of songs in 1995, you went to a store and paid for them, because there was essentially no other way to get those songs. Even if you wanted to steal the music, you had to pay some price: you needed to have a friend with the right CD, and you needed time and blank CDs to make a copy.

But on the internet, there's no scarcity: there's an endless amount of everything available to everyone. The laws of supply and demand don't work terribly well when there's infinite supply. Swift is right that "important, rare things are valuable," but she's failed to understand that the idea of rarity simply doesn't exist in the digital marketplace.

This is such a huge idea that our perceptions of appropriate behavior in this market are still being hashed out, because our inherent sense of right and wrong is still tied to physical objects. Most people wouldn't shoplift a Taylor Swift CD or a Transformers DVD from Best Buy, but I don't know anyone who feels particularly guilty downloading pirated music or movies. We all know that bootleg DVD stands are doing something illegal, but the internet literally went black to protest SOPA, a law designed to crack down on digital bootleggers.

Taylor is right that music is art, and that art should be valuable, but figuring out how to value art in a world without scarcity is a problem unlike any other in human history. It's why subscription music services like Spotify are the only way music makes money in countries that have rampant piracy, and it's why Apple had to buy Beats to compete. The only real answer anyone's got so far is advertising, which is probably why Taylor's RED tour was sponsored by Keds and product placement is so rampant in music that the Chris Brown song "Forever" was literally an extended Doublemint gum jingle in disguise.

Taylor Swift is right about how valuable she is

But Taylor's not all wrong: she points out that some artists "break through on an emotional level" and their fans "cherish every album they put out until they retire." She points out that her fans had all seen her latest tour on YouTube already, and that she wanted to surprise them with special guest performers. "We want to be caught off guard, delighted, left in awe," she writes.

That's exactly right. People will pay to go have experiences they treasure, and they'll pay for spectacles like a Taylor Swift show. And they'll pay to get a piece of someone they've connected with — that's why there are hundreds of teen YouTube stars you've never heard of selling out shows around the world. "In the future, artists will get record deals because they have fans — not the other way around," writes Taylor. We're in that future now; that's where Justin Bieber came from. Here's Iovine again, noting that people will pay for experiences, but not for simple access to music. "It's not enough."

But hitting that tipping point is almost impossible for the vast majority of artists working today, and their inability to actually sell music means they have to sell other things — and making all those other things means they'll have less time and money to put into making their music. It's a vicious cycle, and it means that being Taylor Swift is perhaps more valuable than Taylor Swift's music.

After all, Taylor Swift is a scarce resource.