Divided No More

The creation of a battlefield park at Antietam was contentious and uncertain, much like the battle itself

ON SEPTEMBER 17, 1867, a large cadre of dignitaries and interested parties descended on Sharpsburg, Md., a province of rolling hills just east of a bend in the Potomac River. Having lost its bid to become the county seat of Washington County a century before—a distinction that went to Hagerstown to the north—Sharpsburg had retained its sleepy quality well into the 19th century. Therefore, a crowd of such stature was certainly unusual—but not unprecedented. It was exactly five years before, after all, that the town had ballooned from its normal population of 1,300 to about 100,000, during and after the maelstrom of Antietam.

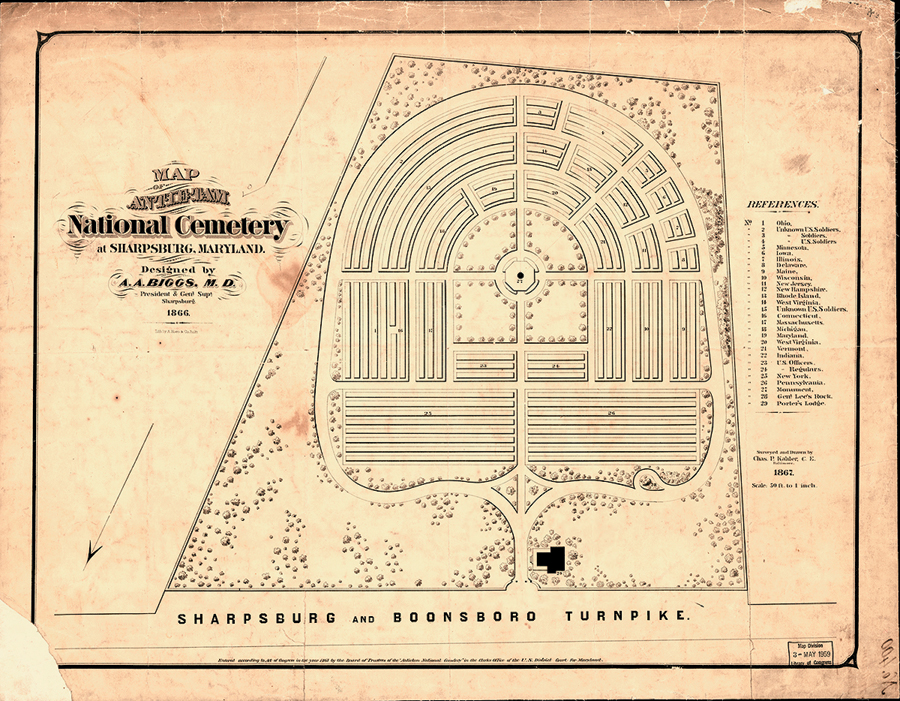

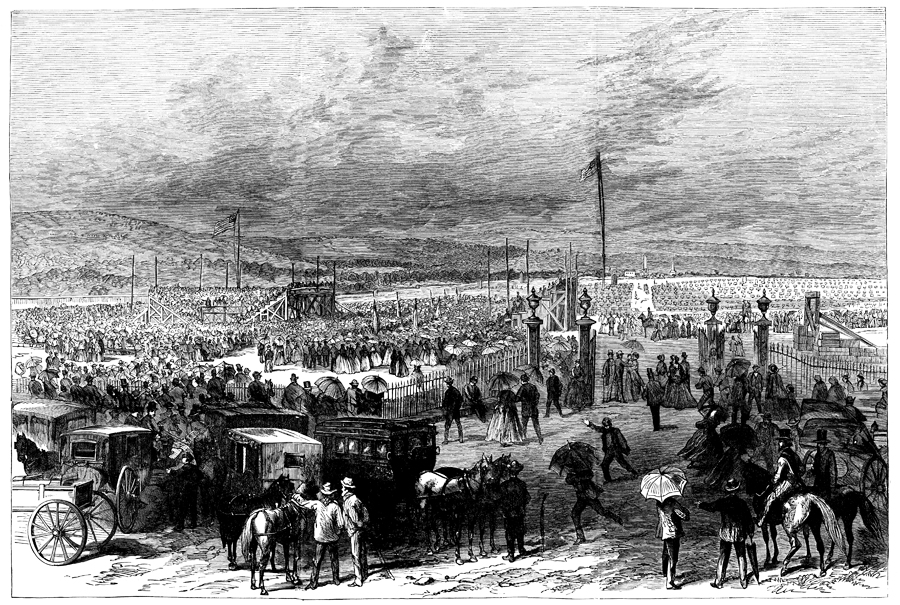

This day, by contrast, was meant to be more serene; a crowd of nearly 15,000 had assembled to dedicate the new Antietam National Cemetery, to pay final respects to the Union soldiers whose bodies had once littered the fields and who had now been re-interred in the cemetery (nearly 5,000 in all, representing 19 states). Located atop a hill east of Sharpsburg, the cemetery encompassed 9½ acres, with the burial plots set in a handsome semi-elliptical pattern. Men and women in hats and bonnets had arrived from near and far, some carrying umbrellas in preparation for the storm gathering overhead, which seemed to reflect an unspoken tension in the air. Along with several state governors and other dignitaries, one of the day’s speakers was President Andrew Johnson. The North Carolina–born Johnson was supportive of Reconstruction and was conciliatory toward the South, something the pro-Union crowd didn’t appreciate, especially with the memory of the high casualty count at Antietam so close at hand. When Johnson rose to speak, he was met with tepid applause and more than a few hecklers, and he and his entourage fled shortly afterward. The New York Tribune called the ceremony “a stupidly farcical affair.”

It was an inauspicious beginning for what would eventually become Antietam National Battlefield. As a border state, Maryland’s loyalties were divided during the war and just as divided when it came to memorializing its most famous battle. Even as the Unionists were hustling the president off the stage at Sharpsburg, for example, still others were working to include a section in the cemetery for the Confederate dead—a controversial effort that brought deep sectional feelings to the fore once again. It would be the work of several more decades to establish both the physical boundaries of the park and, just as important, the message the park was sending to the residents of Maryland and the nation beyond.

The first phase of memorializing the Battle of Antietam began almost as soon as Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia retreated across the Potomac. For months and even years afterward, the field was littered with the detritus of war: bullets, cannon balls, soldiers’ accoutrements and, gruesomely, skeletal remains. As park historian Ted Alexander writes in his book The Battle of Antietam: The Bloodiest Day, a Union soldier passing through Sharpsburg two years after the battle remarked that, at every stop, “the eye rests upon something to remind the traveler of that awful day of carnage.”

At Antietam as elsewhere, relic hunters began collecting these items and passing them around parlors as objects of conversation—a nascent effort, one might say, to interpret what had occurred there. (Even a notorious boulder on the battlefield, known as “Lee’s Rock,” was subject to appropriation—see p. 37.) It wasn’t long before the nation’s first Civil War souvenir shops were open for business. O.T. Reilly, only 5 years old at the time of the battle, would amass such a collection of artifacts that he opened a novelty store in Sharpsburg years later, selling candy on the main floor and relics in the basement, according to historian Stephen Recker. Although Sharpsburg has never had the bustling tourism that, say, Gettysburg has enjoyed (for good or ill), attracting visitors has long been part of the battlefield’s history.

Preserving and interpreting the landscape was a decidedly more complicated business. At Antietam, the primary concern in the immediate aftermath of the war was burying the dead. But even that was fraught with controversy from the beginning, as conciliatory legislators (including Maryland Governor Thomas Swann) sought to reserve a section of the new cemetery for Confederate soldiers. In Washington, D.C., according to park superintendent Susan Trail (whose doctoral dissertation, Remembering Antietam: Commemoration and Preservation of a Civil War Battlefield, is an authoritative source on the development of the park), the Chronicle ran an editorial calling the plan to include Confederates akin to interring, “side by side with loyal men who perished to save the Government, the traitors who sought to destroy it.” Union factions ultimately prevailed, and the Confederate dead of the Antietam Campaign were buried instead in Hagerstown and Frederick in Maryland, and in Shepherdstown, W.Va.

The New York Tribune called the cemetery dedication ceremony ‘a stupidly farcical affair’

“In the end, locating the Confederate cemeteries away from the battlefield represented a step toward the battlefield becoming a Union landscape,” writes Trail, “one upon which Confederate soldiers had little place.” At least Maryland officials were willing to acknowledge the Confederate losses enough to allow burials within their state, Trail adds. She points out that the Confederates who perished at Gettysburg were transported out of Pennsylvania altogether, primarily to Richmond.

In July 1879, the cemetery was transferred from the private Antietam National Cemetery Association to the U.S. War Department, thus beginning the long period of federal government oversight at Antietam. It would coincide with a growing impetus to turn the battlefield into a commemorative landscape through the erection of monuments. The largest of these is the Private Soldier monument that stands at the center of the cemetery—depicting a 21-foot-high soldier at parade rest. Including its pedestal, the monument stands 44 feet tall. With his U.S. belt buckle displayed so prominently, Trail says, the monument struck another blow for the Union and against a spirit of reconciliation with the South.

But a generation is a long time—long enough for healing, and long enough to forget. By the 1890s, writes historian Timothy B. Smith, “the old wounds of the Civil War began to fade into memory as the North and the South developed new issues other than the racial questions that had so divided them.” By that point, nearly half the members of Congress were Civil War veterans, according to Smith, and veterans filled the ranks of state legislatures as well. These men wielded enormous power and influence and, as they began to comb gray hair, they were rightly concerned with the legacies they would leave behind. They turned their attention to preserving what they saw as the five most prominent and symbolic battlefields of the late war—Chickamauga and Chattanooga, Antietam, Shiloh, Gettysburg and Vicksburg.

But even in this “golden age” of battlefield preservation, things did not come easy at Antietam.

In light of all the changes and threats the 20th century wrought upon other battlegrounds, Antietam remains incredibly well-preserved, hauntingly like it was in 1862. This is especially remarkable given that the legislation establishing the battlefield park covered only the rights of ways for the park roads, not the large farms between them. Although Congress offered widespread support for creating a national battlefield park at Antietam, after setting aside large tracts of land at Chickamauga, Ga., the legislators realized they could save money at Antietam by focusing solely on acquiring the roadways and thin strips of land on either side—what Ted Alexander calls a “minimalist approach” to preservation. They also established the Antietam Battlefield Board, whose first two agents were Col. John C. Stearns of the 9th Vermont Infantry and former Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth. They were tasked with mapping out troop movements and staking out what would become the park boundary.

The work was slow and difficult; eventually Stearns resigned, and Major George B. Davis became president of the board (he was later succeeded by George W. Davis, who was not related). Stearns’ departure had opened the door for Ezra A. Carman, who had himself fought at Antietam and had steadfastly gathered information on the battle ever since. He was soon named the board’s “historical expert” and worked tirelessly with both of his Davis colleagues to lay out the park road scheme, draft the text for the iron interpretive tablets that would line those roads and negotiate with landowners who were willing to sell. Slowly, the battlefield came together. In 1900, Congress appropriated funding to name the battlefield’s first superintendent—Charles W. Adams.

Although the battlefield plan had solidified, relations between the park and the townspeople were sometimes rancorous. This was never more true than in the spring of 1912, when Superintendent Adams had taken a stand that farm machines and cattle were forbidden to travel on park roads. One Sharpsburg resident, Charles Benner, took such offense to this and other perceived slights by the superintendent that he approached him on the morning of June 6, 1912, and shot him several times—leaving his lifeless body, somewhat ironically, lying on a park road. Benner, whom one newspaper called “maddened with drink,” then went home and turned the gun on himself. Incidentally, Adams had been superintendent when the 90th Pennsylvania Association placed one of the battlefield’s most distinctive markers on Cornfield Avenue—a stack of three rifles from which hung a kettle with an inscription that read, in part, “Let us have peace.” (The monument fell into disrepair around 1930 and was replaced with a replica in 2004.)

Despite the challenges, the turn of the 20th century saw a growing appreciation for—and acceptance of—conciliatory efforts toward the former Confederacy. In 1900, the most significant manifestation of this change of heart came in the form of the Maryland Monument, the classical domed structure just north of the park’s visitor center and the iconic Dunker Church. It remains the only monument on the battlefield that honors soldiers from both sides. When it was dedicated on Memorial Day, approximately 20,000 people attended, including several generals and then-President William McKinley, himself an Antietam veteran who would soon have a monument to his service dedicated there. “I am glad to meet on this field the followers of Lee, Jackson, Longstreet, and Johnson,” McKinley said, “with the followers of McClellan, Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan….This meeting after these many years has but one sentiment, love for Nation and flag.”

With the healing passage of time, McKinley’s reception was no doubt far different than the one lobbed at President Johnson 33 years earlier.

By the time the War Department turned control of the battlefield over to the developing National Park Service in 1933, it was simply a case of luck and geography that the battlefield had remained wholly unspoiled. The acreage owned by the government was shockingly small—only about 65 acres. It was only with the celebration of the Civil War centennial in the 1960s and the Park Service’s new Mission 66 program for park improvements—which saw construction of modern visitor centers such as the one at Antietam and the recently demolished Cyclorama building at Gettysburg—that Congress appropriated more funding for land acquisition at Antietam, bringing its acreage up to about 600. That number held until the 1980s, with a series of battlefield expansions bringing the current acreage up to about 3,200.

The park now faces the challenge of adapting its signage, trail markers and other interpretive materials to encompass all the property that has been added to the park since those early park roads and signs were laid out by Ezra Carman and his colleagues more than a century ago, when acreage was minimal. Park staff are now engaged in creating a new long-range plan for literature and signage, which will not only reflect the additional acreage but broader cultural and societal themes as well. Also under consideration are different ways of bringing this information to the modern visitor, who might want to get information through a mobile app instead of an iron tablet.

Critical preservation work continues as well. This winter, for example, a small but significant section of Burnside Bridge collapsed. Although the bridge was stabilized and repaired, Trail says the failure is an indication of potentially greater structural issues that must be addressed.

“My emphasis here is to get all our historic structures and buildings to a good condition,” Trail says. “You always want to leave something better than you found it.”

In the not too distant future, it will be time for another ceremony at Antietam. In 2017, the park will celebrate the sesquicentennial of the national cemetery. With the wounds of war still fresh, it was nearly impossible for many to consider honoring the enemy when the cemetery was created. A century and a half later, however, with its pristine fields still undisturbed by suburban sprawl, and its solemn markers to Union and Confederate dead, it’s impossible to think of Antietam as anything but a place of peace.

Former Maryland resident Kim O’Connell writes regularly about history and preservation for national and regional publications.

This article was originally published in the September 2014 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.