A common blood test could help diagnose cancer earlier, according to research suggesting a high platelet count is strongly associated with the disease.

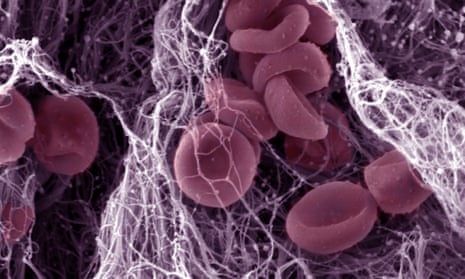

Platelets are tiny blood cells that circulate in the body, helping wounds to clot. But in some individuals too many platelets are produced – a condition known as thrombocytosis, thought to affect about half a million people in the UK over the age of 40.

Researchers say that raised platelet counts are as good a predictor of getting any cancer as a lump in the breast is for breast cancer.

“This is a clue which can be used in practice by GPs to help them select patients for further investigation … most excitingly in some patients who may not already have other symptoms of cancer to achieve earlier diagnosis,” said Sarah Bailey, co-author of the research from the University of Exeter.

Previous studies have suggested a link between thrombocytosis and various cancers, with recent guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence advising high platelet counts could be a sign of cancer of the oesophageal, stomach, lung or uterus.

But it remained unclear whether the condition could signal an increased risk of all cancers, and how it ties in with factors such as age and sex.

Writing in the British Journal of General Practice, Bailey and colleagues report how they examined data from almost 50,000 individuals aged 40 or over who had been given a blood test by their GP. The patients were selected at random from a national database.

In total, over 31,000 patients found to have a raised platelet count, and nearly 8,000 without, were included in the analysis.

Within a year of the blood test, the team found that cancer was more common among those who had thrombocytosis: 11.6% of men and 6.2% of women were found to have cancer compared to 4.1% of men and 2.2% of women without a raised platelet count. In the general population about 1% of individuals over the age of 40 develop cancer each year.

For comparison, among women aged between 50 and 59 who have discovered a breast lump, the proportion who are found to have breast cancer is 8.5%.

“We found cancer was more commonly diagnosed in men with raised platelet counts than it was in women with raised platelet counts and we believe that is because there are more causes of raised platelet counts in women that are not cancer,” said Bailey.

The team add that cancer was more common among for those who had thrombocytosis for longer. Of the men who had a raised platelet count of the same value or higher six months after being diagnosed with thrombocytosis, 18.1% developed cancer, while for women the figure was 10.1%.

While many different types of cancer were present in both groups, the team found that breast and prostate cancers were less common among those with thrombocytosis than in the general population, while lung and colorectal cancers were more common.

For about a third of cases of lung and colorectal cancer in patients with thrombocytosis, there had been no other symptoms that raised the suggestion of cancer. That, say the researchers, makes testing for raised platelet count a valuable tool, and could speed up cancer diagnosis by at least three months for thousands of patients a year.

Richard Neal, professor of primary care oncology at the University of Leeds who was not involved in the research, welcomed the study.

“This is an excellent study that demonstrates the potential for a commonly used blood test to identify some patients with cancer earlier,” he said. “This work should begin to change practice, so that GPs should be testing patients with raised platelet counts for cancer, especially those without other potential cancer symptoms,” he added.

Dr Jasmine Just, Cancer Research UK’s health information officer, said more research was need to confirm whether further tests following a high platelet count would save lives.

“There are lots of possible reasons a person’s platelet count might be high, and in most cases it won’t be down to cancer,” she added.

“Measuring platelet count in patients who don’t otherwise warrant a blood test is not necessarily a good idea. But if a patient has a blood test for another reason and a high platelet count is found, then one of the possible diagnoses doctors should consider is cancer.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion