My deep attachment to my e-reader is greeted by slightly offensive surprise from those who expect readers of my generation to be sentimentally fond of old bindings, and resistant to new and bewildering technologies. Those who express this surprise are almost invariably non-readers themselves, who prefer coffee table to content. The e-reader certainly sorts out the sheep from the goats, and divides those who need to read from those who like to turn the pages.

Let me dispel one myth. The e-reader, although technologically advanced, is in no way bewildering. It may take you an hour or two to acquaint yourself with it, but once you know how it works, its basic principles are simple. Unlike the proliferating array of mobile phones and DVD recorders and programs that plague us, the e-reader is easy to handle, and it does exactly what you want it to do. It enables you to read, anywhere, anytime, almost anything. It enables you to purchase or acquire texts at midnight, in the small hours, on a train to Taunton, at a bus stop, in a bunk on a ferry in the Arctic Circle. Don't tell me there is no romance in buying ebooks: what could be more romantic than sitting in the sun by the breaking white and turquoise waves on an island in the mid-Atlantic, enjoying a pleasant lunch and conversing about William Blake, and finding yourself able to find the quotation you half-remember with a click of a finger? And all, if you so choose, for free? Blake, the device shows us, is almost obsessively fond of the word "Atlantic", make of that what you will, and the lines tell us that Time rages in vain, for, "above Time's troubled Fountains / On the Great Atlantic Mountains / In my Golden House on High/ There they Shine Eternally".

The e-reader's capacity for research and inquiry seems almost limitless, and I have not got to grips with its full potential. I know how to make notes and how to highlight, and I managed to get rid of that annoying program that tells you the passages that other people liked best. This had some curiosity value and I can see it could be entertaining, but not to me. I was alarmed when my first device, given to me by my family for Christmas three years ago, suddenly started to speak to me: I didn't know it could do that and wasn't sure how to tell it to shut up. That model was stolen, from under my chair in the British Library cafe, and its replacement is whiter and brighter and, as far as I can tell, silent. My present device is just about perfect. So far.

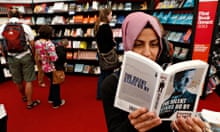

There are so many ways of reading, and they complement one another. At a Wordsworth study day last month, 20 of us were equipped with an impressive variety of texts: hand-annotated 50-year-old school copies of the Collected Works in tiny print, new and old scholarly editions from OUP and Penguin, even a facsimile of Joseph Cottle's original 1798 printing of the Lyrical Ballads. (That's mine, and treasured.) And some of us had e-readers. Between us, we could find anything we needed. One version doesn't drive out another. I have Doris Lessing's Golden Notebook in a signed hardback first edition, in a ragged paperback, and also, for ease of reference and for travel, on my e-reader. It's a big book, and the lightweight e-version is handy.

As we get older, books and bags get heavier. The e-reader is the answer to happy travel and baggage restrictions. The Canary island on which I purchased Blake is idyllic in many ways, but it has no bookshops. The e-reader allows you to shop as you go, or when you arrive. It has handy built-in dictionaries. It allows you to read in the full glare of the sun, or in the darkness of your hotel bedroom. The e-reader is also wonderful in hospital. Gone is the panic of running out of reading matter. You can find whatever suits your bedridden mood – detective stories, highbrow fiction, history, tales of survivors and your old friend the Guardian, which will pop into your device every day at a bargain price. I still buy and greatly prefer the print version, but the online Guardian, when the paper version is unavailable, is a great comfort.

You can work it with one hand, and you can enlarge the font of your device to suit your eyesight. I met a middle-aged man who found the act of reading almost impossibly difficult: he had poor vision, had been diagnosed as dyslexic and was prejudiced against books. His Kindle had converted him: in huge print, he had managed to read a short thriller, and had found the experience exciting. He thought he would go on reading, slowly but pleasurably, in the kind of privacy the e-reader offers. He had joined the reading world.

The privacy can have its downside, as you can't easily spy on what others are reading and engage them in cultural conversation. Reading Karl Ove Knausgaard in Norway this Easter, I longed to ask fellow Norwegian travellers what they thought of this sensationally successful Nordic novelist, which would have been easier had I been able to display a thick volume with his name on it. (I've never seen the hardcover of the English translation.) I tracked down a Norwegian copy of his memoirs in a bookshop in a small coastal town called Bodø and took its photo with the bookseller, but that wasn't a very interactive experience.

E-readers are wonderful for fat books. Like many others, I read Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch in tablet form, and learned to navigate my way around its excessive length by highlighting bits of plot I knew I was going to find confusing and names of minor characters I was sure to forget. You can personalise your copy and make it your own. I have occasionally read an entire work without realising that there was a useful glossary at the end, or without finding (as in Michael Frayn's memoir) the section with the photographs, but I'm getting better at looking, and publishers are getting better at publishing them.

The new technology is hard on traditional booksellers; I recognise that, and am not sure what they or we can do about it. But publishers are rapidly getting to grips with it, and I believe that in the future I will profit from it as author and as reader. Maps and illustrations still aren't as good on screen as on the printed page, but I sense that all that is changing. In a slightly luddite way, I am fixated on the black-and-whiteness of my device, but I am aware that new wonders are on the way. I am delighted that some of my backlist is appearing in e-format, and rejoice in the colourfulness of its new virtual jackets. I still don't want a multifunctional tablet with movies and emails, I want one for reading only, but I can feel myself being tempted into colour. The future is bright.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion