Manufacturing power is down but niche companies can buck the trend

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The future is far from rosy for many manufacturers in Europe but Roberto Gavazzi, chief executive of Boffi, a top Italian maker of upmarket kitchen and bathroom units, is upbeat.

“I am very confident that the current difficult markets are getting better for the best brands,” he declares.

Underlying this sentiment is Gavazzi’s belief that Boffi – like many other European manufacturers of a similar mould – has built up strengths not just in product creation but in using service and design skills to offer customers something special that would be hard to obtain from rival businesses.

“Consumers are even more selective – they want to choose only those products that have a real added value,” he says. “So [they choose] not only design and function, as is normal for our collections, kitchens and bathrooms, but now they want increasingly to buy something that gives them a very special mood or atmosphere. Here, I think we can do well.”

Making marine instruments for jobs such as measuring the salt concentration in sea water or locating underwater objects such as mines is a very different industry sector. But Matthew Quartley is also looking to the future with some optimism.

Quartley is the managing director of Valeport, a UK company that is among the leading businesses globally in its field. It has recently invested £2.5m in a new production and commercial centre at its base in a quiet corner of southwest England, a sign of confidence that the company is ready to continue its substantial growth of recent years.

“We have a staff of 75 while in 2003 we employed only 30,” says Quartley. “The new investment has given us room to breathe.”

Boffi and Valeport are among hundreds of top manufacturing businesses based in Europe that have eschewed mass market, commodity-style sectors. Instead they have concentrated on narrow “niche” areas of industry where often fairly small enterprises can command a global presence.

Other attributes shared by these manufacturers include reliance on specialist technical skills, an emphasis on product customisation and use of “hybridised” supply chains that combine the far-flung with the local. For example, European businesses keep costs under control by purchasing standardised components and materials from low-wage economies. At the same time they maintain strong links with key local suppliers that make design-intensive components and assemblies that are often crucial to the final product.

But the positions of many of Europe’s specialist manufacturers have inevitably been harmed by the deep economic difficulties of recent years, linked particularly to the 2007-08 financial implosion.

Meanwhile the rise of manufacturing in China and other fast-growing economies has greatly reduced the share of leading European countries in global manufacturing output, which (excluding Russia) fell from 28 per cent in 2000 to just over 21 per cent in 2012, according to UN data.

Even Germany dropped from 7 per cent to 6 per cent over the period, while Britain’s share halved to just under 2 per cent.

With large swathes of mainstream industry, including cars, white goods and steel, suffering severe falls in demand, manufacturing employment in the EU between 2007 and 2013 declined by roughly 10 per cent, equivalent to a loss of some 3m jobs. Despite a recent recovery it remains sluggish.

It might seem surprising that so many leading specialist companies are feeling cheery. Take Enrico Krog Iversen, chief executive of Universal Robots, a Danish producer of highly adaptable industrial robots that work on production lines around the world.

Universal Robots, which was founded in 2005, has 100 employees and relies on a network of about 25 key suppliers based in Denmark that make many of the crucial engineering assemblies and parts. “Europe has many of the important technical skills and some strong clusters of technology-based businesses. For our sort of manufacturer, I don’t see any major challenges ahead,” Iversen says.

Such views are not universally shared. Alberto Alessi, general manager of Alessi, the Italian maker of upmarket kitchen goods and other products, says: “I’m not at all optimistic for the future of manufacturing in Europe. In a world where consumer products tend to [move] to industrial commodities without soul or character, high production costs will make the [European position] too difficult.”

But the balance of opinion leans towards optimism. So how have the most successful European small to mid-sized production businesses managed to cling on to – and sometimes extend – their global capabilities? One answer is that they have stuck to their key strengths built around specialist products or machines where the relative smallness of the market – plus the difficulties of replicating the required degree of know-how – act as a big barrier to potential competitors.

For instance, Blum of Austria has built up a leading position in the narrow field of hinge and fastener systems for furniture. It holds 1,200 patents covering the esoteric aspects of “motion control” for doors and shelving units and it sells 1,100 different varieties of hinge.

Similarly specialised is Belgium-based IBA, which is the world’s biggest supplier of novel machines for treating cancer patients by directing streams of protons at the affected areas. About 25,000 patients have been treated on IBA equipment – which the company says is more than on all competing installations combined – with the cost of a machine plus ancillary equipment varying from $25m to $50m.

Sometimes a company can use its strength in a narrow product area to extend its reach into related fields that rely on the same basic technology but take it into a different market. In this way, Vitronic, a German company that uses laser scanning in instruments that measure the speeds of road vehicles, has moved into areas such as laser-based identification systems for monitoring the movement of goods in warehouses and factories.

The success of some leading European businesses is also linked to their ability to extend their reach on a global level while retaining a strong base in their home country.

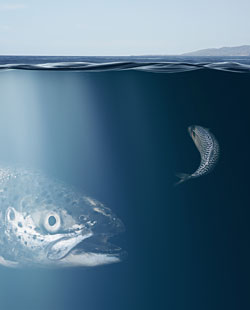

Baader of Germany is a leader in the field of fish-processing machines, suited to handling different species of fish and which both automate messy jobs such as removal of bones and extraneous tissue and reduce the risks of contamination. The company has extensive global connections – just over half its 1,100 employees are outside Germany – but the main production is done in Baader’s home country.

Sometimes the emphasis in terms of global connections causes the domestic aspect of the company’s operations to shrink, while its overseas activities increase. Thus Bisazza of Italy – a leading maker of decorative mosaic tiles – has reduced its workforce in Italy over the past five years while extending its manufacturing and assembly plants in countries such as Mexico, India and China.

More frequently, however, top European manufacturers go in both directions at once. Trumpf, the German company that is the world’s biggest maker of laser cutting machines for sheet metal, recently underlined its commitment to overseas expansion through the purchase of JFY, a leading Chinese machine maker. But its key production and development centre remains in its base in Stuttgart, which employs a quarter of the company’s 10,000-strong global workforce.

Nicola Leibinger-Kammüller, Trumpf’s president, plays up Germany’s strengths in specialist mechanical and electronic technologies. “Germany, and in particular our home region of Baden-Wurttemberg, are for us still the best machine construction locations in the world,” she says.

Also, many of the top manufacturers in Europe say that remaining at the highest level in terms of technology capabilities is an essential part of their ability to keep ahead of competitors in other nations such as China and India that may have the benefit of lower costs.

However, Fabio De’Longhi, chief executive of De’Longhi, the Italian company best known for its consumer domestic appliances such as coffee machines and kettles, says that attempting to innovate by channelling money towards research in new materials and electronic control mechanisms is only part of the story. What is needed, he says, is matching these efforts with thinking about the requirements of the customer. “Only those companies capable of delivering meaningful innovation – innovation that improves the consumption experience and delivers benefits that consumers can perceive – will remain ahead of the curve in the future.”

Hans Langer, chief executive of EOS, a German company that is among the top producers globally of novel families of 3D printing machines, has a similar emphasis on developing technology while at the same time listening to customers. “In close co-operation with [customers], we will push the technology to the next level,” he says.

Comments