Is There Such a Thing as an Affordable Lawyer?

For many Americans, legal services are out of reach. But that's beginning to change.

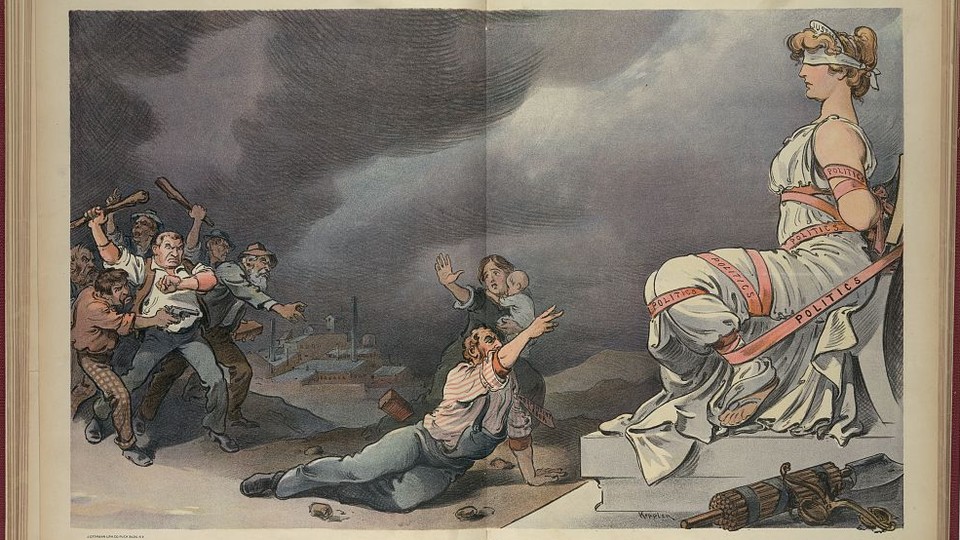

One of the most perplexing facts about our perplexing legal market is its failure to provide affordable services for just about anyone but rich people and corporations. In a democracy steeped in rule-of-law, justice-for-all platitudes, this lack of access to affordable legal help can feel worse than perplexing—it can feel like an outrage. Slowly, however, the system is evolving.

To think about the problem, consider the case of Ned Henry, the plaintiff in a landlord-tenant dispute that’s commonplace in most ways—and curious in one.

In late 2012, Ned and his partner—recent tenants in an apartment in California’s East Bay—began to feel sick. Ned developed migraines and psoriasis, while his partner suffered headaches and nausea. As the winter progressed—more time inside, windows closed—the symptoms got worse. Eventually, they hit upon an explanation: toxic mold poisoning. They moved out and filed a lawsuit, both to avoid a penalty for breaking their lease, and to recover the costs that the mold and the move had imposed.

Ned and his partner didn’t have a lot of money—and the move had depleted their assets—but they weren’t exactly poor, either, so they looked into hiring a lawyer. They couldn’t, however, find anyone within their budget who would take their case. “It was definitely more than we could afford,” he told me over the phone last week. “Big range, depending on who we called, but at least $3,000-$5,000 on the low end, to start out.”

Priced out of the market for a representative, Ned and his partner decided to represent themselves in small-claims court, a less formal venue for legal disputes where attorneys are generally prohibited. After more than a year of legal wrangling, they finally brought their landlord to court this February and won. (The case is now on appeal; even if the judgment is upheld, it will likely take them years—perhaps even until the landlord dies—to collect.)

It’s within that year of legal wrangling that Ned’s story diverges from the norm. Ned, unlike most Americans, has a B.A. from Harvard and a doctorate in physics from the University of California at Berkeley. Those facts aren’t relevant simply because they make him an educated guy with experience wading through complex jargon. They’re also relevant because they granted Ned access to friends and acquaintances with legal expertise who could give him advice throughout the process—as he communicated with his landlord and the court, assembled evidence, and crafted his arguments.

These advantages helped Ned achieve justice, at least for the time being. He notes, however, that, because of his own background and the counsel of his friends, he was much better prepared for court than the average citizen. “Everyone else had big piles of papers that they had to dig through,” he recalls of other plaintiffs in court, “and no one else got their evidence considered because the judge wasn’t going to dig through all that.”

In contrast, Ned was able to navigate the court’s bureaucratic maze of paperwork, jargon, deadlines, and locations (even small-claims court can be Byzantine). “It was confusing for me even with lawyers to give me advice and my own education,” he recalls. “If I hadn’t had those things, I would not have been able to figure out what the hell they were talking about half the time.”

The implication that you might need multiple degrees to represent yourself in a basic civil dispute seems unfair in and of itself. But a lack of access to affordable legal representation—coupled with the obstacles facing anyone who wants to self-represent—imposes knock-on costs that ripple throughout society.

Ned, for example, was a victim of the system before he was a participant in it. After digging into his landlord’s past, he learned that she had already dealt with mold issues and failed to disclose them on the lease he signed, and that a dozen or more previous tenants had attempted to hold her accountable for abuses over the past decade. These attempts, he learned, tended to result in failure: “Somewhere along the small claims process the tenant just gives up and stops doing it because it’s a huge pain in the ass.” And the frustrations of the process are only exacerbated by the broader chaotic situation that prompts the disputes. “It’s at a time when it’s already hard,” Ned reflects. “Nobody is suing somebody at a time when they’re not already dealing with hard shit.”

Lack of access to legal help, in other words, serves as a shield for neglectful landlords and all sorts of other bad actors—abusive husbands, predatory lenders, corrupt employers. Because it took someone with Ned’s advantages to hold her accountable, his landlord was free to fleece tenants for years.

Ned’s experience is not unique. As a recent law review article notes, “The typical legal services consumer in the U.S. makes approximately $25 per hour, and is priced out of the services lawyers provide even at low attorney rates of $125-$150 an hour.” Those rates are well below the standard rates shown in the 2013 Laffey Matrix—a set of fee guidelines compiled within the U.S. Department of Justice—which start at $245 for a greenhorn associate.

The access problem looms large for legal-services attorneys, who receive funding to provide free legal help to people near or below the poverty line, but often find the income cut-offs arbitrary and counterproductive. Steven Eppler-Epstein, executive director of Connecticut Legal Services, points out that, alongside all the deserving poor people he has to turn away because of inadequate funding, it can be equally frustrating to have to turn away so many who are near poor or even middle class. (There is no right to counsel in civil cases—only criminal—and a 2009 Legal Services Corporation report found that “for every client served by an LSC-funded program, one person who seeks help is turned down because of insufficient resources.”) Eppler-Epstein notes the high percentage of people in family court without legal representation—surveys across states have put the number around 80 percent—and the high price of law. “[These people] may be over income for us,” he explains, “but they still can’t afford a lawyer because a lawyer says, ‘Well, if I’m going to get involved in this case and it’s going to go on for a year and a half … you’ve got to pay me $10,000 up front.’ And who’s got $10,000?”

Ned’s story is also—unlike most of the cases that legal-aid lawyers like Eppler-Epstein deal with—not off-the-charts heartrending. And that’s the point. Ned is a well-educated guy, roughly 30 years old, with a small (if not enormous) amount of disposable income—he’s exactly the kind of person for whom the free market has historically been great at cheaply packaging desired goods and services. Even for complicated services, like income tax preparation, the market has largely succeeded. Why has law lagged?

One compelling set of answers comes from University of Southern California law professor Gillian Hadfield, who explored the imperfections of the legal market in a February 2000 law review article.

Legal services have a lot of qualities, Hadfield argues, that give lawyers leverage to charge high rates. Perhaps the largest is the complexity of law, which does not just require that lawyers receive expensive schooling and certification, but also necessitates specialization within the profession and obscures how much help—and which specific strategies—are necessary to win. Moreover, because winning is based on drawing “distinctions and/or similarities that were not previously recognized” but which then become part of the body of law for settling future disputes, the complexity of the law is constantly expanding. There is, in Hadfield’s words, “a natural entropy” to legal complexity.

Because of its complexity, Hadfield points out, legal help is what economists call a “credence good”—a good “provided by an expert who also determines a buyer’s needs” because the buyer is “unable to assess how much of the good or service they need; nor can they assess whether or not the service was performed or how well.” The classic examples are auto repair and dentistry, but most legal services qualify, too. Just as the average consumer is unable to verify how many cavities he has or how many auto parts he needs replaced, he’s often unable to question a lawyer on just how many hours of lawyering will be sufficient to resolve his problem. The effect is a pernicious lack of transparency “about the actual value of a lawyer.” And since the costs are sunk in the event of a loss, there’s a strong incentive for already-paying clients not to skimp.

The legal profession also operates, Hadfield notes, within what is essentially a “monopoly on coercive dispute resolution”: If you have a legal issue you don’t really much choice about where to go. You have to deal with a system controlled by lawyers, all of whom have come up through the system.

The cost here, Hadfield argues, “is not so much the moral hazard or exploitation of market power for private gain by the profession, as it is the inertia and unresponsiveness of an insulated service provider”—a system that doesn’t readily transform itself. “Innovations in dispute resolution—be they addressed to considerations of justice or cost—are muted and limited,” Hadfield writes, “to what will occur to a group of people who share, by virtue of their professional training and tutored identity, a largely common set of ideas, perceptions, and norms about dispute resolution.”

This monopoly—and the fact that it is controlled by creatures of the monopoly—chills disruptions that might otherwise shake up the market. And there are plenty of disruptions to be had: Hadfield and other thinkers have pointed toward a number, including allowing a greater ambit for paralegals to provide legal help in appropriate circumstances (Hadfield notes in a 2010 Washington Post op-ed that “In England, Australia and the Netherlands…a wide variety of professionals and experts can provide legal assistance”); allowing non-lawyer-owned companies to sell legal services (as the British supermarket chain The Co-op has recently begun to do); and embracing technological change. On this third point, Hadfield observes:

The legal equivalent of TurboTax is probably just around the corner, if not already on British computer screens. Meanwhile, in the United States, the bar is filing class-action lawsuits against fledgling online legal providers such as LegalZoom and shutting down alternative providers who threaten local lawyers' markets and offend lawyerly sensibilities. Many American judges and lawyers continue to insist that the only model for legal services is one-on-one advice with an attorney. No corporations, no venture-capital-backed entrepreneurs, no intelligent software to complete legal documents, no community groups or nonprofits.

Here Hadfield gestures at one academically popular explanation for why the legal market hasn’t liberalized enough to lower prices: that the organized bar doesn’t want it to. The Economist recently called this problem “the restrictive guild-like ownership structure of the business”; citing “parochial anxieties about ceding turf to nonlawyer competitors,” Stanford Law professor Deborah Rhode has suggested the bar’s policies amount, ultimately, to “economic protectionism.”

While there’s no doubt the bar is guilty of foot-dragging, the full critique doesn’t quite wash. The bar’s most persuasive alibi is that it has every interest in getting more consumers to purchase legal help—and the current price of legal help keeps an enormous number of consumers on the sidelines. As Hadfield points out in her Post op-ed, 30 to 40 percent of Americans with legal problems report, across surveys, doing nothing to address them; in Britain, that number is just five percent. This group is part of what legal futurist Richard Susskind calls the “latent legal market”:

the innumerable situations, in the domestic and working lives of all non-lawyers, in which they need and would benefit from legal guidance (or earlier, more timely, or empowering insight) but obtaining that legal input today seems to be too costly, excessively time consuming, too cumbersome and convoluted, or just plain scary.

In time, Susskind predicted in his 2008 book The End of the Lawyers?, this latent demand would be unlocked. The good news: He was right.

Hadfield wrote about the “legal equivalent of TurboTax” being “just around the corner,” but even that phrasing understates its proximity, when it’s been in her next sentence the whole time. LegalZoom—which Hadfield castigates the bar for fighting—basically is the legal equivalent of TurboTax: a largely do-it-yourself legal warehouse that allows users to generate (and, in some cases, file) legal forms through sophisticated online software. For an added monthly fee starting around $10, people can now also get advice (and “attorney-drafted letters on your behalf”) from a lawyer through the website.

One of the turnoffs with do-it-yourself law—and which seems to account for the organized bar’s issues with LegalZoom—is the degree to which it cuts lawyers out of the equation. The complexity of law makes DIY feel perilous, the same way it’s a scary proposition to rewire your house if you’re not a trained electrician, regardless of whether Home Depot will sell you all the supplies you need. Most people sense this risk; my friend Luke Palder, a small-business owner who runs a proofreading service, mentioned the other day that he’s wary of do-it-yourself legal services, even though he’s sensitive to price. “I'm willing to pay a little bit more for a lawyer's oversight,” he told me, “even if I'm doing most of the heavy lifting.”

Perhaps the most interesting model to enter the space—between largely unaffordable brick-and-mortar law and the heavy-DIY of a Legal Zoom—is Rocket Lawyer. Founded by Charley Moore in 2008, funded by Google Ventures, and now boasting a team of nearly 200 employees, plus a network of 450 on-call attorneys—Rocket Lawyer has, in effect, scaffolded the do-it-yourself model with more support from actual lawyers. Like LegalZoom, Rocket Lawyer offers customers the tools to create and file documents on their own electronically, but they also build the ability to consult with an attorney into their core product. Moreover, if a dispute arises—“and this is where it becomes incredibly valuable to people,” Moore says—customers can hire a lawyer to represent them from within the company’s legal network for 40 percent of the lawyer’s published rate.

Moore, a former Naval officer and Gulf War veteran, recalls the dichotomy between the legal help he received in the military and the legal system he encountered as a civilian. He recalls getting into a car accident that wasn’t his fault—another driver had run a right light—and being able to go to the Judge Advocate General at the Naval Academy for assistance. “It was actually very easy to get a lawyer to help me out, to at least understand the issues and potential claims,” he recalls. “And often it’s that very first place to start—to really take advantage of and be protected by the legal system—that even middle-class people in the civilian world can’t afford.”

Moore's site now clocks 1.6 million visitors per month. Beyond its use of technology to lower costs, what's most striking about the Rocket Lawyer model is the way it disrupts the market imperfections noted by Hadfield to make legal help more affordable.

First, the model helps neutralize the credence good problem by bringing transparency to the market. Rocket Lawyer was the first company at scale, Moore asserts, to bring legal pricing into the open. “Five years ago, if you wanted to know in New York City or Memphis, Tennessee, what a lawyer charged for estate planning or to do a simple divorce, you couldn’t find that out,” he points out. “They didn’t put their fees in the Yellow Pages.”

Perhaps more significantly, the model brings transparency to the quality of legal help offered. Beyond the 40 percent discount, Moore notes, customers know that “they’re going to get a lawyer who’s already been vetted”—not just that they’re a member of the bar in good standing, but that “they’re all—like Uber drivers—reviewed and rated by the users in the system.” And, Moore adds, "we do remove lawyers from the system who get poor reviews after their representation."

In this sense, Rocket Lawyer is a bit like a buyers’ club. “Like Costco,” as Moore puts it, but also a little bit like the American Automobile Association (AAA) or even the now-Hollywood-famous Dallas Buyers Club, two older solutions to classic credence-good problems.

Rocket Lawyer is, likewise, as Moore points out, a market-maker, and that’s likely why Rocket Lawyer has been able to sidestep the bar opposition that has nagged LegalZoom: It’s more a pipeline for customers to find legal aid and less a replacement for that aid. “Most people cannot do this stuff on their own,” Moore insists. “They need professional assistance. And I really equate it to: You can take over-the-counter medicine when you have a certain type of headache, but at a certain point, if you need brain surgery, you’re going to need a neurosurgeon to do that. It’s the same thing in the law. We can help you to understand when you need to talk to a lawyer, but then you’re going to need somebody to represent you in pretty much any substantive legal matter.”

With prices as low as a $250 flat-rate fee for a no-fault divorce, the model has certainly unlocked demand. “It’s sort of like in 1971,” Moore suggests. “Nobody thought that regular folks wanted to fly, and then, voila—when Herb Kelleher and the folks at Southwest Airlines produced a $49 plane ticket, all of a sudden we went from Mad Men, where you were in a suit and tie on Pan Am, to regular folks flying and not taking the bus anymore from Dallas to Albuquerque.”

“We know,” he continues, “that well over half—the vast majority of people who’ve used Rocket Lawyer for legal advice—have never consulted with an attorney before in their life, and that includes small business people. So we are really the on-ramp now for first-time purchasers of legal advice.”

“It doesn’t require a physical tromp over to a lawyer’s office and thousands of dollars,” says Moore. “You can do it on your phone for free.”

Despite its progress in increasing access to legal help, Rocket Lawyer—like its heavier-DIY counterpart, LegalZoom—is not without critics. One of the most compelling critiques comes from Luz Herrera, a professor at Thomas Jefferson School of Law in San Diego, who is skeptical of the “invisible, never-see-the-attorney model” and prefers local, brick-and-mortar community law offices.

Herrera knows the brick-and-mortar model well. After graduating from Harvard Law School, Herrera hung her own shingle in Compton, California, in 2002. She charged “peanuts” at the beginning—$75 for consultations, and $150 hourly—barely scratching together enough to get by. “It really went back to the reasons that I went to law school,” she recalls, “because I went to law school to represent people that were in my family or my community that had legal needs and didn’t understand how to navigate the system. What happened then is that I then got overwhelmed by the people who needed my services and the lack of other affordable options for them. And I could only take what I could take, so there was no way I could help everybody who called.” The experience led Herrera to found a nonprofit, called Community Lawyers, to help “create a pipeline of attorneys that would work in these underserved communities.”

On-the-ground community law matters, Herrera contends, for several reasons.

First, she maintains, having a lawyer is a part of the economic infrastructure of a community—not having one is like “not having a supermarket or church ... it’s a component to a healthy community.”

Second, Herrera explains, in-person contact is important to many clients. “I think [online help] works for some people,” she admits. “It works for the new generation of consumers, people who are plugged in. I don’t necessarily think it works for everybody. I think it depends on how comfortable you are with technology. … The client base that I had [in Compton] wanted to meet individually. People want to develop that relationship.”

Herrera, instead, sees technology as enabling a new viability for the community-law-office model—a way to bring down overheard and allow the middle-class model pioneered by Jacoby & Meyers and Hyatt Legal Services in the 1970s and 1980s to return to dominance. She points out a service called DirectLaw, founded by Richard Granat, which allows smaller firms to integrate technological innovations onto their personal firm websites. “They provide the infrastructure to be able to compete with LegalZoom,” she says.

Even so, the scale problems of brick-and-mortar are formidable. Like a face-to-face LegalZoom, Community Lawyers charges below-market rates for document assistance, but demand overwhelms supply: “There’s a lot more need than there are resources,” Herrera explains, “so we’re only helping a fraction of people who need help.”

Despite Herrera’s critiques, her and Moore’s similarities come across as greater than their differences. Both are looking to increase access to lawyers, and both are ultimately endorsing a model that relies on healthy doses of both technology and client effort.

Community Lawyers, for example, is very much a “collaboration,” as Herrera puts it, between the organization and its clients: “we bring in attorneys who provide pro bono consultations, but the consumer of legal services goes and files the documents—we don’t do any of that,” she explains.

“I think that’s what limited-scope representation is about,” she continues, citing Sue Talia, a family law specialist and expert on limited-scope legal representation. “Talia writes about the ability to form a partnership with the client, and that the attorney and the client have to have a conversation about what you can do, what can’t you do—‘If you only have a thousand bucks, is it better for me to fill out the form, or is it better for me to just review it and go with you to the hearing?’”

“Full-service representation is no longer the primary model,” Herrera states plainly. “The primary model is ‘Let’s see how much lawyer we can afford.’”

Involving clients in their own legal help is, interestingly, less a new idea than a resurrected one. John Tobin, the longstanding executive director of New Hampshire Legal Assistance (NHLA), recalls that the approach of enlisting the client was much discussed in the early days of legal aid, when the War on Poverty was still a heady new idea. “When legal aid first started having paralegals,” he recalls, “the notion was to have community people, not bright college students.” Thirty years ago, Tobin notes, these discussions yielded mixed results, but more recent experience is encouraging. He reports:

We have had people who helped us a lot on their own cases, and who help us on some of our bigger cases—help us organize other clients, help us understand the system, be part of the litigation team. It makes a big difference. And these days, we are asking more of our clients—we’re asking them to do more of the gathering information and pulling together evidence and getting the documents and all those things. Because we don’t have the resources.

The model certainly would have worked for Ned Henry, who did all of his own legwork anyway, coached in part by his lawyer friends.

But the echo from the history of legal aid that Tobin notes raises an important question about access: Does the end of full-service representation mean an even bigger hurdle for the poor—especially those, like Herrera’s clients, without ready access to (or comfort with) technology, or people who are hampered by mental health problems or intellectual disabilities?

It shouldn’t. If technology and new models like Herrera’s and Moore’s are able to bring costs down and expand access for a large number of people, the access problem for the smaller number of hardest cases should be easier to solve. For one, by drawing more clients into the paying market, firms like Rocket Lawyer may free up much-needed bandwidth in legal aid, where firms are already forced, as Tobin puts it, to make excruciating “Sophie’s Choice decisions about which cases to take.” Second, the march of technology can cascade into legal aid, improving access there, too. Just a few years back, New Hampshire’s Legal Advice & Referral Center (NHLA’s sister organization) installed new phone- and web-based systems that brought its case production numbers to some of the highest in the country.

Moore, for his part, recognizes that, as his company grows, legal help for those who can’t swing even Rocket Lawyer’s rates will be an issue he’ll need to address. “Right now,” he admits, “we do steer people to legal-aid societies if they do not have any ability to pay, but I would be the first to say that we can do more … and I fully intend to do more in terms of supporting pro bono legal services by our lawyer network.”

In the meantime, the slow rise of Moore or Herrera’s hybrid model—part lawyer, part layman, part computer, in varying ratios—offers hope for a legal market in which the non-rich can afford to buy, though they may have to invest some sweat equity in the purchase. And in that sense, the legal market—perhaps because of its complexity, or perhaps because, as Herrera notes, lawyers simply “aren’t trained to be entrepreneurs”—is just catching up with other new-economy markets for the middle class. After all, TurboTax and H&R Block offer us affordable tax preparation services, so long as we’re willing to serve as the clerks to our electronic CPA. Travelocity and Kayak offer us more affordable travel, so long as we’re willing to serve as our own electronic travel agents. For most of us—tenants with sleazy landlords, small business owners, people in bad marriages—these sweat-equity options represent progress. And so long as they don’t harm—and instead help—the worst off, these options are progress.

As this new legal model slowly gains footing, it’s worth pausing to consider the new, partial-service attorney—less a sovereign champion and more a supervisory ally. Taking up this latter role, the limited-scope lawyer resonates with Harvard law professor Charles Fried’s decades-old idea of the lawyer, like the doctor, as “special purpose friend.” Fried, in his essay, was arguing for the lawyer’s moral legitimacy in preferring his or her client’s interests to others’ (even if it means harming those others’ interests), but the simile has expressive power beyond Fried’s philosophical mission—it conjures To Kill a Mockingbird’s Atticus Finch more than Chicago’s Billy Flynn. Fried conceived of the legal relationship as one in which the “friendship systematically runs all one way,” but the collaboration entailed by the limited-scope model renders the relationship a two-way street. In a marketplace that’s felt closed off to most non-rich Americans, it sounds, if not perfect, like a fair deal.