Please Turn On Your Phone in the Museum

Cultural institutions learn to love selfies, tailor-made apps, and social media.

Earlier this year, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, visitors paraded through the fifth floor to see a retrospective dedicated to the abstract expressionist Frank Stella. Although many of the works on display were four or five decades old, in some ways the show felt tailor-made for the Instagram age: a riot of vibrant colors and textures, 20-foot-long reliefs, and sculptures as jagged and dynamic as 3-D graffiti.

Visitors one busy Saturday afternoon stopped in front of artworks, lined up shots on their phones, snapped a few photos, and then moved on to the next piece. Some paused briefly to consider a particular painting; more stared down at their screens, furiously filtering. Few noticed an elderly gentleman sitting on a bench in one of the smaller rooms, watching the crowd engage with his work. The only visitor in the gallery not clutching a phone was Stella himself.

Museum directors are grappling with how technology has changed the ways people engage with exhibits. But instead of fighting it, some institutions are using technology to convince the public that, far from becoming obsolete, museums are more vital than ever before. Here’s what those efforts look like.

1 | Curating for Instagram

About five years ago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art took a small step that has proved monumental: It stopped entreating visitors not to use their cellphones. The decision was driven by a recognition that cellphones are omnipresent in modern society, and fighting them is a losing battle. “People ask me what our biggest competition is,” says Sree Sreenivasan, until recently the Met’s chief digital officer. (He’s now the chief digital officer for New York City.) “It’s not the Guggenheim; it’s not the Museum of Natural History. It’s Netflix. It’s Candy Crush.”

Accepting that cellphones are here to stay has led museums to think about how they can work with the technology. One way is to design apps that allow visitors to seek out additional information. The Brooklyn Museum, for example, has an app through which visitors can ask curators questions about artworks in real time. Museums including the Guggenheim and the Met have experimented with beacon technology, which uses Bluetooth to track how visitors move through galleries and present them with additional information through an app. Beacons have the potential to offer detailed histories about works, and directions to specific paintings or galleries.

Sreenivasan points out that once museum apps incorporate GPS technology, visitors will be able to plot their path through galleries just as they now plan their commute on Google Maps—no more getting lost in the Egyptian wing or staring at a paper map in search of a particular Monet sunrise.

Embracing cellphones also means that more art galleries will curate immersive, Instagram-friendly exhibitions. The staggering success of the Museum of Modern Art’s Rain Room, a moody gray space illuminated by falling water, and the Renwick Gallery’s Wonder, a collection of vibrant, room-size installations, has shown what an effective marketing tool social media can be. Some museums even arrange art with the amateur photographer in mind. “The ways in which people are interacting with works have changed, and so that changes, a little bit, the way we space the works,” says Dana Miller, the director of the Whitney’s permanent collection.

2 | History and Art, Augmented

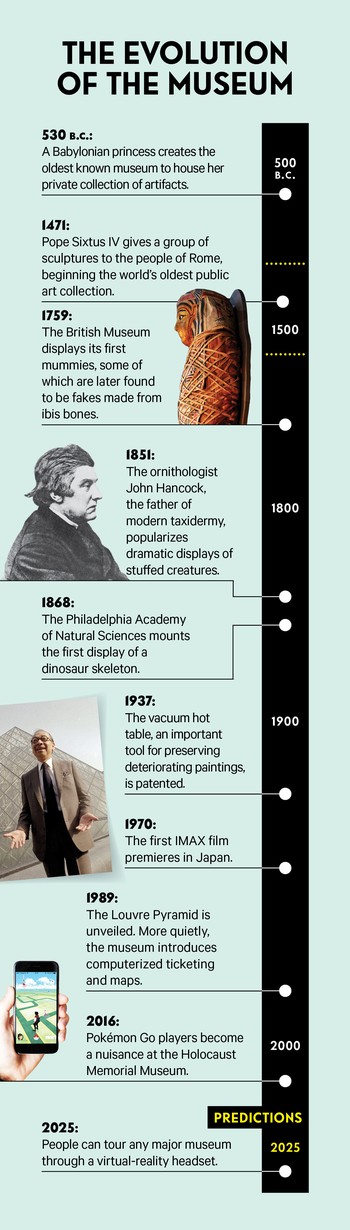

Pokémon Go, a hugely popular game that projects cartoon characters onto the real landscape seen through your cellphone, has caused headaches for institutions like the Holocaust Memorial Museum, which had to ask visitors to refrain from playing. But the game also points to how technology can enhance in-person experiences rather than simply drawing people further into their various devices.

In museums, augmented reality might mean an app that brings paintings to life via your phone’s camera, or that encourages visitors to learn about history by competing to “collect” artifacts or experiences. The Royal Ontario Museum has experimented with using augmented reality to add flesh and skin to dinosaur bones, and with using a scanner to project images of animated beasts that follow visitors through galleries. A project at the University of Southern California is collecting testimony from Holocaust survivors with the aim of producing interactive 3‑D holograms that can answer questions from visitors.

Virtual reality, too, promises to become part of the museum-going experience. The British Museum has experimented with using virtual-reality headsets to let visitors explore a Bronze Age home, or see what the Parthenon might have looked like thousands of years ago. At the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture, visitors can use virtual reality to feel what it was like to be a diver who helped recover a slave ship. “It’s about helping people remember that what they’re experiencing was actually real,” says Lonnie Bunch, the museum’s director. “What we really want to do is humanize history.”

3 | Museums in Your Pocket

Some museums are putting the entirety of their collections online. The Whitney’s Dana Miller says museum directors initially feared that doing so might deter people from visiting, but in fact they’ve found that it can lead to an increase in visitors. The Rijksmuseum, in Amsterdam, has gone one step further by making its collection available as open data, so people can reproduce, edit, and play around with works. Institutions such as the Met, the British Museum, and the Smithsonian are encouraging people to download specifications so that they can 3‑D-print replicas of artifacts in the museums’ collections.

The point isn’t just to get more people through the museum doors, but also to reach those who can’t visit in person. In 2011, the Google Art Project launched, putting works at many of the world’s biggest institutions online in super-high resolution. The project currently features works by more than 6,000 artists in more than 250 museums. In July, Google updated its Arts & Culture app, allowing people with Google Cardboard headsets to “tour” 20 museums and historic sites around the world. Perhaps one day, some museums won’t have a physical presence at all. Instead they will curate digital exhibitions and change displays quickly to respond to global events in real time.

4 | Art Will Adapt to the Viewer

For thousands of years, people have made art using variations of the same methods—paint is applied to a surface; material is shaped into a sculpture. But artists are increasingly experimenting with pixels, algorithms, 3‑D printers, and other tech tools to make works that evolve and respond to the environments around them.

In 2013, the National Portrait Gallery commissioned a portrait of Google’s co-founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, that was rendered in part as a moving visualization of their words fed through Google’s search engine. A new exhibition at London’s Somerset House about the singer and artist Björk uses virtual reality to let visitors experience her music on a deserted beach in Iceland, or even inside Björk’s mouth while she’s performing.

One can imagine sculptures that use sensors to move around as people walk through galleries, or artworks that respond to changes in their surroundings, so that repeat visitors see something different each time. Already, immersive installations use light and tricks of the eye to distort reality and perspective—inevitably, they’ll use technology to do the same thing, to more dramatic effect.

Visitors themselves may become part of the art. A 2015 exhibit at London’s Design Museum used hidden cameras to take pictures of people gazing at artworks and then displayed those “portraits” back to the unwitting subjects. That exhibit and a recent one at the Whitney by the filmmaker Laura Poitras collected data from people who were using the museums’ Wi‑Fi and then exhibited the data back to them as they left, to illustrate a point about the electronic footprints we all leave behind.

Just as the Library of Congress has acquired Twitter’s entire archive to add to its permanent collection, museums will increasingly acquire artworks that aren’t physical objects at all, leaving a more dynamic and richer image of the 21st century for future visitors to marvel at.