One night in 2011, the New York gallery Boo-Hooray hosted an exhibit of infamous B-movie director Ed Wood’s trash paperback novels. Woods wrote the books in mere days and sold them to pornographic publishers under a variety of pseudonyms. At the time, his novels of suburban iniquity and cross-dressing contract killers were disposable dreck. Today, they’re carefully preserved in Cornell University’s rare-books collection. A press release emphasized the difficulty of tracking down Wood’s digitization-defying work: "The paperbacks are truly rare, even in an age of mass-searchable used book engines, and Google ferocity."

Boo-Hooray’s curators went to great lengths tracking down Wood’s novels, but their jobs could have been harder, if not impossible, if Wood had been writing today. Like many prolific pulp authors, he might have been selling ebooks through Kindle or another self-publishing platform. But while paper books might be harder to distribute, they have one huge advantage over ebooks: as long as an archivist or collector can keep them from falling apart, they’ll be as readable in a century as they will in a year. Keeping ebooks in the historical record is harder. How do you preserve something that can’t be locked in an archive, sold in a secondhand bookstore, or even converted to a new format without first navigating an arcane copyright system?

So far major publishers have done little more than flirt with digital-only releases. Clifford Lynch, director of the Coalition for Networked Information and a strong proponent of ebook preservation, sees this as a temporary calm. "I believe that that is going to change, and probably change pretty suddenly and pretty soon," he says. When it does, libraries will have to figure out a way to keep them on shelves after publishers have changed formats, stopped licensing them, or closed up shop altogether.

The idea of a 'copy' no longer makes sense

For years, archival work was aided by the first-sale doctrine: if someone bought a copy of a book, movie, or album, they were free to resell it, rent it out, or keep it forever. Digital media upset this model. The very idea of a "copy" no longer makes sense — technically, just syncing a file to a Kindle makes a new copy, let alone "lending" it to someone else. In 2010, an appeals court decision effectively shut down any digital version of the first-sale doctrine. Vernor v. Autodesk established that you couldn’t "buy" a piece of software, only — at best — acquire a permanent and non-transferable license to it.

For libraries and mass-market publishers, this has proved a point of contention. "If you look at the whole history of public libraries and ebooks, it’s been very ugly, frankly," says Lynch. Penguin froze its ebook-lending program in 2011, citing "new concerns about the security of our digital editions." The same year, HarperCollins instituted a 26-loan cap for each license. Libraries often end up getting temporary access to ebooks in a particular format, while publishers worry that a single library ebook will end up being shared as widely as a pirated one. It wasn’t until last year that all six (now five) major publishers got on board, and ebooks are still wrapped in complicated and clunky DRM systems.

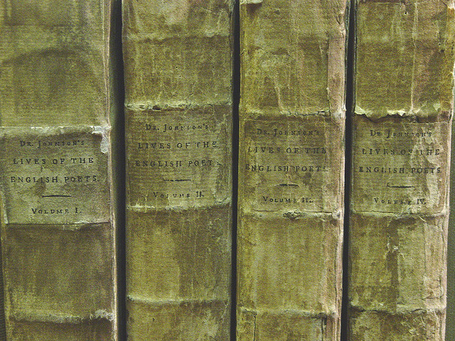

Rare books at Harvard's Houghton Library (Flickr / DiscourseMarker)

Public libraries, which often just want large numbers of popular books and don’t deal in preservation, can compromise on licensing. Research libraries, where books are kept for the historical record, are a different story. In academia, library archivists can make sure ebooks survive by brokering deals with publishers and third-party storage services like Portico, which hold scholarly literature in a kind of escrow. Publishers allow Portico to keep future-proof copies of a book or journal in its database, and libraries buy access to its services. In the event of a "trigger," which could include the work going out of circulation or the publisher ceasing operations altogether, Portico releases the material to its members. But the more adversarial relationship between libraries and mass-market publishers, as well as libraries’ relatively weak bargaining position, makes a non-academic version of Portico a non-starter.

"You’re speaking to an institution that is in its birth pangs."

As long as publishers keep selling physical books along with ebooks, the latter can safely be ephemeral. But Amazon has already begun to experiment with exclusive digital-only pieces from high-profile authors like Amy Tan and Chuck Palahniuk. (And in 2009, alongside the release of the Kindle 2, Stephen King published an exclusive digital novella about a mysterious pink Kindle that connects its reader to parallel dimensions.) Where authors get the freedom to experiment with new formats and pricing models, Amazon has the power to quietly revise or delete books without notice — in one bizarrely poetic incident, it temporarily removed copies of 1984 from users’ Kindle libraries. Earlier this year, Stephen King pulled his 1977 book Rage from print, but it remained available — if somewhat pricey — in the used market. If he chose to do the same for the Amazon-exclusive essay where he wrote about that decision, you’d have to hope it was republished elsewhere and hold tight to your Kindle in the meantime.

While publishers and libraries work through these issues, there’s one entity that can theoretically get around almost any restrictions: the Library of Congress, tasked with preserving historically meaningful media long after its commercial value is gone. Whenever an author or publisher wants to officially register a copyright for a print book or ebook, they submit two copies to the US Copyright Office, and the Library of Congress can pick noteworthy titles to store. It also has its own relationships with publishers, which are willing to work with it in exchange for metadata like Dewey decimal classification and subject headings. Yet the Library of Congress is only beginning to address these problems.

Card catalog, Library of Congress (Flickr / Paulo Ordoveza)

"You’re speaking to an institution that is in its birth pangs," says Library of Congress project manager Carl Fleischhauer of digital preservation. He and Lynch are both preoccupied with technical questions as well as legal ones. The Library of Congress works with publishers to get DRM-free files that can be migrated to different formats over time, a luxury that rules against breaking copy protection can make dicey. It also works on developing tools to prevent content from being degraded or corrupted, including a piece of software called BagIt, which wraps content into self-contained, folder-like digital "bags" complete with a manifest listing everything that should be preserved.

As troublesome as preserving text-only files can be, it’s relatively straightforward compared to what ebooks could one day become: interactive pieces of media that blur the line between website, game, and database. Even mathematical symbols have turned out to be hard to format correctly. "Culturally, we still seem to have this sort of dichotomy in our heads," says Lynch, between ebooks and other digital artifacts like websites and games. "We’re having a terrible time intellectually, as well as technically, understanding what preservation means for this latter menagerie of things in the digital world."

"Think about your ability to buy a physical book, read it, put it in the attic for 50 years, or give it to a grandchild."

Setting aside the problems of complicated multimedia projects, self-published pulp ebooks from places like Smashwords or Kindle are particularly vulnerable. The age of vanity-press books, says Lynch, is giving way to one where leaving big publishers behind is a "hard-nosed business decision," but archival work hasn’t caught up and books can slip under libraries’ radar — especially if they’re not written by authors who are already well known. Self-published books are harder to collect in bulk than ones put out by major publishing houses, and it’s doubtful that all smaller authors will take the time to send preservation copies of their books to the Copyright Office. Even if they do, the files could just end up as casualties of the Library of Congress’ culling process.

Most of those casualties will not be great. Many of them will be trash, rarely purchased and quickly forgotten. But today’s niche fiction and even patently offensive mistakes are tomorrow’s historical record, and they may be in the greatest danger. Genres that were considered juvenile or unimportant in their day — pulp science fiction, romance novels, comic books — have since proved to have lasting literary value or cultural importance. "Libraries, mostly research libraries, missed these things when they first came out," Lynch says. "They just dismissed them." Later, they filled out their shelves with secondhand copies from collectors. But no one will be able to donate their favorite ebooks to a library or send them to a used bookstore. There’s no market in seeking "rare copies" of items that a buyer could duplicate endlessly but never distribute. "One of the things that is interesting about digital is that it’s hard to be a collector," says Lynch. "Think about your ability to buy a physical book, read it, put it in the attic for 50 years, or give it to a grandchild. As opposed to getting something on your Kindle and hopefully having it still available in 50 years, and being able to give it to anyone."

Kindles and copyright, it turns out, may be killing the collector. And even if you never look for a yellowed copy of Orgy of the Dead or Suburbia Confidential in some library archive, it’s a loss for all of us.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/14708230/2335481597_3143b0f138_z.0.1412665014.jpg)