In cramped offices just a few hundred metres from Buckingham Palace, the crack troops of the war against fake news are on high alert.

Professional fact checkers, economists and statisticians are among 25 staff being part-funded by Google and Facebook to protect the UK general election from fake news in an initiative run by Full Fact and First Draft, two fact-checking organisations, the latter battle hardened by tours of duty in the US and French elections.

One night this week they scanned the internet as usual for false reports and misleading claims about the election gathering traction on social media. A piece being shared thousands of times on Facebook about Jeremy Corbyn rang alarm bells.

“Corbyn confirms a Labour government would pay £92bn Brexit bill in full,” ran the headline on an apparent news site called YourBrexit.co.uk.

The team’s software was predicting the story would get strong traction in the coming hours. It was predicted to hit 12,000 shares and was already up to 4,000 shares on Facebook. Only the most popular articles go that viral.

But the story looked wrong. Corbyn hadn’t quite said that.

There was something else too. Another piece of software revealed that YourBrexit.co.uk was registered to the same Google advertising account as a satire site called Southend News Network, which has featured fake stories such as “Seafront on lockdown after Somali pirates take over Southend pier”.

The byline looked a little odd too. It was Walter White, the name of the crystal meth dealing antihero of US TV series Breaking Bad.

The first step was to bring in the fact checkers, secondees from the House of Commons library and the government statistical service, legal experts, social researchers, and criminal justice and home affairs specialists.

As for the Corbyn story, what was true was that the Labour leader had been asked by reporters on Monday if he would agree to pay an exit fee to the European Union before beginning trade talks. What he had said, according to the Press Association, was: “Clearly where there are legal obligations on long-term investment projects both in this country and other places, they must be adhered to, we must honour them.”

The Evening Standard had run the story as: “Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn hints he would pay £85bn Brexit ‘divorce bill’ if PM”, but YourBrexit went further. It was wrong, not least because estimates of the cost of Brexit vary hugely.

Full Fact and its director, Will Moy, alerted news desks that the YourBrexit piece “misrepresented” what the Labour leader had said.

But who was behind the false claim? The site’s information page said it was recently set up to inform users about developments on Brexit, but every one of the 10 or so stories it publishes daily is geared towards attacking remain supporters or backing leavers.

Is it run by the Southend News Network which has a linked ad account. That spoof site has at times slipped into fake news. When it reported last year that the M25 was to close for a week so it could be used for an endurance race, the story was picked up in good faith and reported on LBC radio.

SNN is run by Simon Harris, an Essex teacher who until now has tried to guard his anonymity. He has confirmed to the Guardian that he owns the domain to YourBrexit, but said Walter White was the pseudonym of a 19-year-old student in Southend “who is fed up with the liberal elite”.

“I don’t have time to check all the stuff he writes so he tends to make more mistakes,” said Harris.

The student, who spoke to the Guardian on condition of anonymity, publishes YourBrexit from his bedroom while also studying for exams, but that doesn’t stop his site generating significant traffic.

He claims that a million people click on YourBrexit each month and he has a reach through Facebook of 3 million. It earns him several hundred pounds a month in ad revenue although he says he would do it for free. “I’m fed up with the constant anti-Brexit news stories and decided to do something about it,” he said.

He defended the Corbyn story, saying: “I do not believe we have slipped into fake news,” adding: “I would never publish anything that is deliberately fake news to boost the Brexit cause. It is immoral.”

The skirmish over Corbyn’s quote is part of a much bigger war being fought against fake news, which flies faster than ever with the existence of 32m Facebook accounts in the UK.

“The challenge we are facing every day is there is a bunch of bullshit out in the world, but if we debunk stories that are not going anywhere we give oxygen to these rumours,” said Claire Wardle, a director at First Draft. “We are in an information war.”

The fact that the UK polls are not as close as they were between Clinton and Trump is cited as one reason why fake news has not, so far, become such a big issue in the UK election.

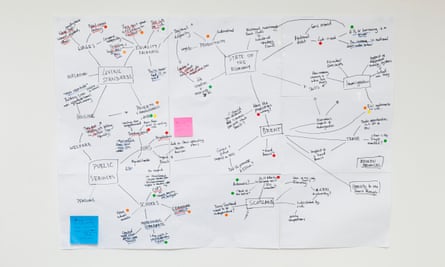

But those in the war room in London are on the look out. On the wall is a dizzying “issues map” charting the terrain over which these fact checkers expect to roam. It was drafted hastily when the election was called and a three-year plan leading to the 2020 election was torn up, with Full Fact placing itself on a higher footing. Main topics include “living standards”, “state of the economy”, “Brexit” and “Scotland”. Orbiting each are sub-topics. “Breaking point” connects to the NHS, “Did Vote Leave promise £350m” is attached to Brexit and “grammar schools” links to public services. Connected to nothing is the topic “broken promises”.

“It requires an extraordinary level of concentration,” said Moy. “It is not our job to tell the story with broad brush strokes; it is about getting the details right.”

Every fact is checked by two different people before Full Fact’s verdict is made public. When Full Fact started in 2010, said Moy, you could easily list the number of media outlets with an audience of more than 100,000 people.

“Now you can have entire city’s worth of people looking at one thing and its not in the usual place where we have been checking. One Facebook post can get an audience as big as a political magazine or even a political TV show.”

Currently FullFact alerts newsrooms in the mainstream media but perhaps there is a way of tackling the fakery where it is being propagated?

“If there is a really big conspiracy theory circulating in an alt-right group are we effectively going to put in a truth bomb and think that will make a difference? Probably not. So we need to think if there are parts of the community that are more likely to be persuaded by a fact check.”

It looks set to be a busy three weeks.