On April 25, 1974 the Carnation Revolution replaced Portugal's authoritarian regime with a multi-party, democratic system, marking the beginning of what Samuel Huntington called the "third wave of democratization." Four decades later, political differences between the two main political parties, the Socialist Party (PS) and the Social Democratic Party (PSD), have yet to produce any differentiated impact on the country's public finances and economic performance. In short--political differences in ideology and praxis between the parties are irrelevant.

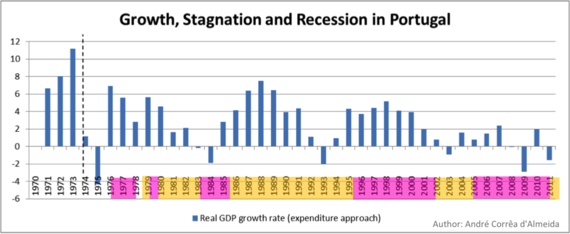

In the last forty years, periods of economic growth, stagnation, and recession have occurred in equal measure irrespective of which party held the power. An examination of these economic periods reveals that any one political party's influence is no more or less beneficial than any other. Since 1974, Portugal has experienced consecutive-year economic growth at four distinct periods: 1976-1982, 1985-1992, 1994-2001 and 2004-2007. In total, Portugal's economy grew in 30 of its 40 post-1974 years (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Growth, Stagnation and Recession in Portugal Source: Authors' configuration; GDP (IMF); Electoral Results (Comissão Nacional de Eleições)Note 1: Years highlighted in pink correspond to periods of Socialist rule. Years highlighted in orange correspond to periods ruled by Social Democrats. The period from 1970 to 1974 (until April 25th) corresponds to the last years of the authoritarian regime. The period from 1974 to 1976 corresponds to the so-called "Provisory Governments" prior to the adoption of the new Constitution in 1976. The second half of 1978 was ruled by an independent government.Note 2: The authors classify the eight-month long government of Carlos Mota Pinto (Nov. 22, 1978 - Aug. 2, 1979) as Social Democrat and the five-month long government of Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo (Aug. 2, 1979 - Jan. 3, 1980) as Socialist.

Source: Authors' configuration; GDP (IMF); Electoral Results (Comissão Nacional de Eleições)Note 1: Years highlighted in pink correspond to periods of Socialist rule. Years highlighted in orange correspond to periods ruled by Social Democrats. The period from 1970 to 1974 (until April 25th) corresponds to the last years of the authoritarian regime. The period from 1974 to 1976 corresponds to the so-called "Provisory Governments" prior to the adoption of the new Constitution in 1976. The second half of 1978 was ruled by an independent government.Note 2: The authors classify the eight-month long government of Carlos Mota Pinto (Nov. 22, 1978 - Aug. 2, 1979) as Social Democrat and the five-month long government of Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo (Aug. 2, 1979 - Jan. 3, 1980) as Socialist.

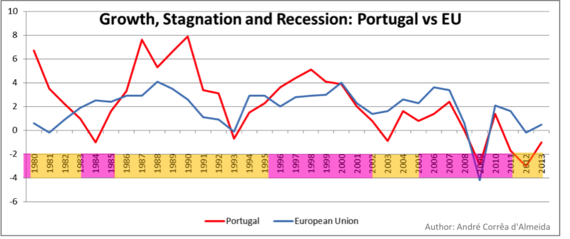

Since 1974, economic growth in Portugal has remained unaffected by political differences between the Socialists and Social Democrats. The first half of the first period (1976-1982) was governed by the Socialists, while in the second half power shifted to Social Democrats. The second period (1985-1992) was governed mostly by the Social Democrats, while the third period (1994-2001) was governed mostly by the Socialists. In the fourth period (2004-2007) power shifted from the Social Democrats to the Socialists. Within the last thirty-five years Portugal outperformed the European Union in three different periods: 1979-1982, under the Socialists/Social Democrats switch; 1986-1992, under the Social Democrats; and 1996-2000, under the Socialists (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Growth, Stagnation and Recession: Portugal vs. European Union (real GDP % variation) Source: Authors' configuration; GDP (IMF); Electoral Results (Comissão Nacional de Eleições)

Source: Authors' configuration; GDP (IMF); Electoral Results (Comissão Nacional de Eleições)

Since 1974, stagnation and recession in Portugal has also remained unaffected by political differences between the Socialists and Social Democrats. Portugal has experienced economic stagnation or recession a total of 10 years since 1974: 1975, 1983-1984, 1993, 2003, 2008-2009, 2011-2013. 1975 predates the existence of both PS and PSD, but all other years show an almost equivalent distribution between the two. Socialists ruled for three years (1984, 2008 and 2009), Social Democrats ruled for four years (1993, 2003, 2012, and 2013), and in the two years coinciding with elections (1983 and 2011) power alternated between the two parties.

Despite the irrelevance of political differences in what concerns the economic performance of the country, in the years since 1976 fervent ideological posturing along party lines has dominated Portugal's policy process. Portugal's post-Revolution constitution permits four-year terms for elected Parliamentarians and correspondent governments, so one might expect that in thirty-eight years Portugal would have seen (roughly) 9.5 government cycles. However, Portugal had seen 19 different governments--twice what might occur under politically stable conditions (e.g., since 1976 the U.S. has had only 10 presidential elections). Moreover, the fact that the Socialists and the Social Democrats have held near-proportionate power--the aggregate number of years in power is 18 and 21 years, respectively--further contributes to the party-polarization in Portuguese politics. Governments' turnover, nineteen where there could have been only nine/ten, is, at least partly, the result of exaggerated popular discourse that encourages such political posturing and exaggerates its effect on policy outcomes.

One consequence of Portugal's "tribalism politics" is that the current politics disproportionately focuses resources, including political energy, on short-term policy goals that can be implemented within the potentially shortened timeframe between election cycles. Uncertainty about term length and the desire to maintain political favor within a shorter timespan undermines the development of sustainable long-term goals, including most needed institutional innovations (e.g., greater political collaboration, new electoral/representative system, a more efficient Parliament).

If the ability to engage in long-term policy-making is one aspect of effective governance, Portugal's current political system is populated with systemic "rules of dis-governance" insofar as such "rules" discourage effective governance from taking hold. "Rules of dis-governance" are the features of the political system that hinder the possibility of collective action based on an "enhanced radius of trust" (Fukuyama 2011, 192) in an otherwise quarrelsome political arena. The result is that Portugal has been unable to effectuate its independence in matters of major institutional development, and it has proved incapable of generating long-term, sustainable policies from within.

There are at least three observations that illustrate the failures of Portugal's political system in developing sustainable, long-term goals. The historical regularity of political-economic crises, which in recent times are occurring with greater frequency, is one such observation. From 1974 to 2003 Portugal faced negative growth in 9-10 year intervals (1974/1975 - 1983/1984 - 1992/1993 - 2002/2003). After 2003, however, the negative growth time interval occurred at the fifth year (in 2008/2009). Secondly, since 1976, all major institutional innovations adopted by Portugal originated from without the country. The principle examples include, the initiation of negotiations with the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1977, the intervention by the IMF in 1978 and 1983, the full adoption of EEC regulations in 1986, adoption of the EURO in 2002, and another IMF intervention in 2011. Finally, the widening of the income inequality gap as illustrated by the fact that in 1976 the richest 0.1% gathered 1.3% of the country's income, but three decades later (2005) this value had already nearly doubled to 2.5%.

The policy-making approach, which favors short-term goals and perpetuates "tribalism politics" is evidenced by the intensity and hyperbolic nature of political intrigue. In turn, meaningful political discourse is shrouded by sensationalist media reports that focus on the quarrelling parties. The cumulative effect of short-term policy-making and the unfounded importance placed on political differences is that political energy and vision needed to develop a more long-term policy-making approach is lost. Furthermore, citizens' attention is unnecessarily diverted away from meaningful, well-informed participation (e.g., strategic policy debates) that might further those long-term objectives.

If key development variables are indifferent to political parties' differences, it follows that the political process should be based on a non-confrontational, cooperative process grounded in elevated political ethics of the common--not the tribal--good.

Blog co-authored with Paulo Reis Mourão, Ph.D, Professor of Economics at the Economics & Management School, Minho University, Portugal.