The following is the introduction to Haruki Murakami’s Wind/Pinball: Two Novels, out August 4th from Knopf.

The Birth of My Kitchen Table Fiction

Most people—by which I mean most of us who are a part of Japanese society—graduate from school, then find work, then, after some time has passed, get married. Even I originally intended to follow that pattern. Or at least that was how I imagined things would turn out. Yet in reality I married, then started working, then (somehow) finally managed to graduate. In other words, the order I followed was the exact opposite of what was considered normal.

Since I hated the idea of working for a company, I decided to open my own establishment, a place where people could go to listen to jazz records, have a coffee, eat snacks, and drink. It was a simple, rather happy-go-lucky kind of idea: running a business like that, I figured, would let me relax listening to my favorite music from morning till night. The problem was, since we had married while still in university we had no money. Therefore, for the first three years, my wife and I worked like slaves, often taking on several jobs at once to save as much as we could. After that, I made the rounds borrowing whatever friends and family could spare. Then we took all the money we had managed to scrape together and opened a small coffee shop / bar in Kokubunji, a student hangout, in the western suburbs of Tokyo. It was 1974.

It cost a lot less to open your own place back then than it does now. Young people like us who were determined to avoid “company life” at all costs were launching small shops left and right. Cafés and restaurants, variety stores, bookstores—you name it. Several places near us were owned and run by people of our generation. Kokubunji retained a strong counterculture vibe, and many of those who hung around the area were dropouts from the shrinking student movement. It was an era when, all over the world, one could still find gaps in the system.

I brought my old upright piano from my parents’ house and began offering live music on weekends. There were many young jazz musicians living in the Kokubunji area who happily (I think) played for the small amount we could pay them. Many went on to become well-known musicians; I sometimes run across them in jazz clubs around Tokyo even now.

Although we were doing what we liked, paying our debts was a constant struggle. We owed the bank, and we owed the people who had supported us. On one occasion, stuck for our monthly payment to the bank, my wife and I were trudging along with our heads down late at night when we stumbled across some money lying in the street. Whether it was synchronicity or some sort of divine intercession I don’t know, but the amount was exactly what we needed. Since the payment was due the next day, it was truly a last-minute reprieve. (Strange events like this have happened at various junctures in my life.) Most Japanese would have probably done the proper thing, and turned the money in to the police, but stretched to the limit as we were, we couldn’t live by such fine sentiments.

Still it was fun. No question about that. I was young and in my prime, could listen to my favorite music all day long, and was the lord of my own little domain. I didn’t have to squeeze onto packed commuter trains, or attend mind-numbing meetings, or suck up to a boss who I disliked. Instead, I had the chance to meet all kinds of interesting people.

My twenties were thus spent paying off loans and doing hard physical labor (making sandwiches and cocktails, hustling foul-mouthed patrons out the door) from morning till night. After a few years, our landlord decided to renovate the Kokubunji building, so we moved to more up-to-date and spacious digs near the center of Tokyo, in Sendagaya. Our new location provided enough room for a grand piano, but our debt increased as a result. So things weren’t any easier.

Looking back, all I can remember is how hard we worked. I imagine most people are relatively laid back in their twenties, but we had virtually no time to enjoy the “carefree days of youth.” We barely got by. What free time I did have, though, I spent reading. Along with music, books were my great joy. No matter how busy, or how broke, or how exhausted I was, no one could take those pleasures away from me.

As the end of my twenties approached, our Sendagaya jazz bar was, at last, beginning to show signs of stability. True, we couldn’t sit back and relax—we still owed money, and our sales had their ups and downs—but at least things seemed headed in a good direction.

* * * *

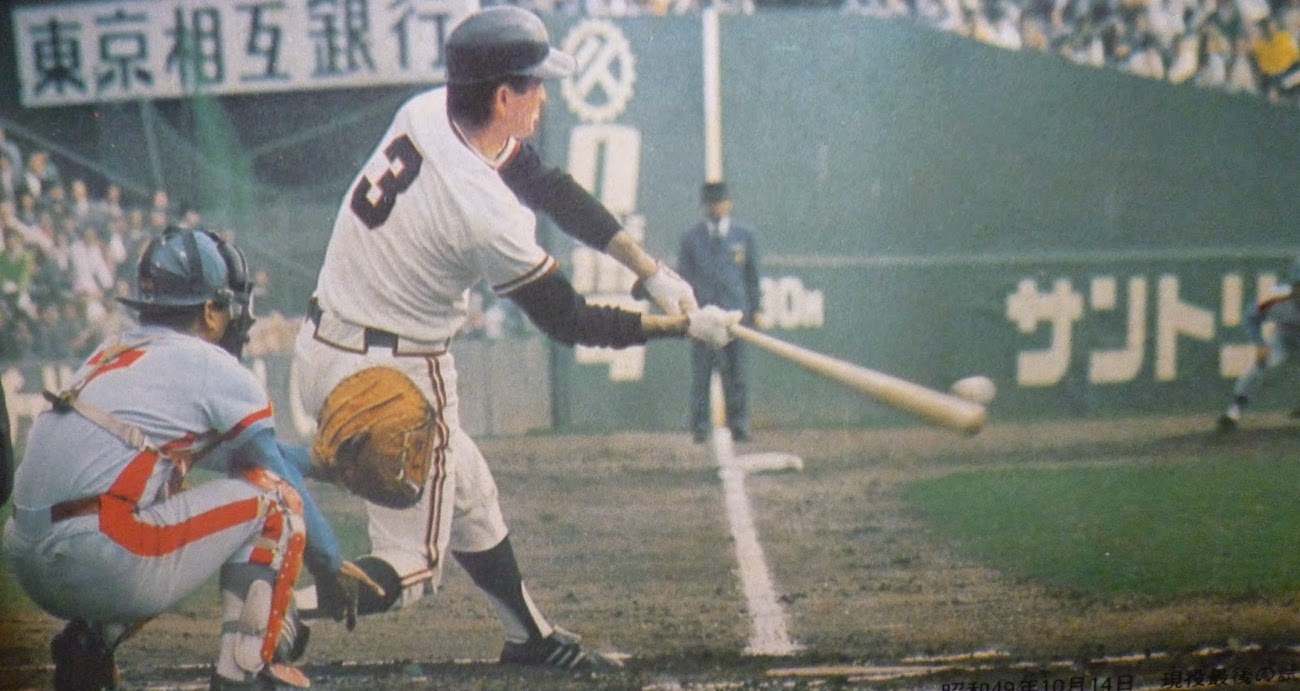

One bright April afternoon in 1978, I attended a baseball game at Jingu Stadium, not far from where I lived and worked. It was the Central League season opener, first pitch at one o’clock, the Yakult Swallows against the Hiroshima Carp. I was already a Swallows fan in those days, so I sometimes popped in to catch a game—a substitute, as it were, for taking a walk.

Back then, the Swallows were a perennially weak team (you might guess as much from their name) with little money and no flashy big-name players. Naturally, they weren’t very popular. Season opener it may have been, but only a few fans were sitting beyond the outfield fence. I stretched out with a beer to watch the game. At the time there were no bleacher seats out there, just a grassy slope. The sky was a sparkling blue, the draft beer as cold as could be, and the ball strikingly white against the green field, the first green I had seen in a long while. The Swallows first batter was Dave Hilton, a skinny newcomer from the States and a complete unknown. He batted in the leadoff position. The cleanup hitter was Charlie Manuel, who later became famous as the manager of the Cleveland Indians and the Philadelphia Phillies. Then, though, he was a real stud, a slugger the Japanese fans had dubbed “the Red Demon.”

I think Hiroshima’s starting pitcher that day was Yoshiro Sotokoba. Yakult countered with Takeshi Yasuda. In the bottom of the first inning, Hilton slammed Sotokoba’s first pitch into left field for a clean double. The satisfying crack when the bat met the ball resounded throughout Jingu Stadium. Scattered applause rose around me. In that instant, for no reason and on no grounds whatsoever, the thought suddenly struck me: I think I can write a novel.

I can still recall the exact sensation. It felt as if something had come fluttering down from the sky, and I had caught it cleanly in my hands. I had no idea why it had chanced to fall into my grasp. I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now. Whatever the reason, it had taken place. It was like a revelation. Or maybe epiphany is the closest word. All I can say is that my life was drastically and permanently altered in that instant—when Dave Hilton belted that beautiful, ringing double at Jingu Stadium.

After the game (Yakult won as I recall), I took the train to Shinjuku and bought a sheaf of writing paper and a fountain pen. Word processors and computers weren’t around back then, which meant we had to write everything by hand, one character at a time. The sensation of writing felt very fresh. I remember how thrilled I was. It had been such a long time since I had put fountain pen to paper.

Each night after that, when I got home late from work, I sat at my kitchen table and wrote. Those few hours before dawn were practically the only time I had free. Over the six or so months that followed I wrote Hear the Wind Sing. I wrapped up the first draft right around the time the baseball season ended. Incidentally, that year the Yakult Swallows bucked the odds and almost everyone’s predictions to win the Central League pennant, then went on to defeat the Pacific League champions, the pitching-rich Hankyu Braves in the Japan Series. It was truly a miraculous season that sent the hearts of all Yakult fans soaring.

* * * *

Hear the Wind Sing is a short work, closer to a novella than a novel. Yet it took many months and much effort to complete. Part of the reason, of course, was the limited amount of time I had to work on it, but the greater problem was that I hadn’t a clue about how to write a novel. To tell the truth, although I was reading all kinds of stuff, my favorites being 19th-century Russian novels and American hard-boiled detective stories, I had never taken a serious look at contemporary Japanese fiction. Thus I had no idea what kind of Japanese novels were being read at the time, or how I should write fiction in the Japanese language.

For several months, I operated on pure guesswork, adopting what seemed to be a likely style and running with it. When I read through the result, though, I was far from impressed. It seemed to fulfill the formal requirements of a novel, but it was somewhat boring, and the book as a whole left me cold. If that’s the way the author feels, I thought, a reader’s reaction will probably be even more negative. Looks like I just don’t have what it takes, I thought dejectedly. Under normal circumstances, it would have ended there—I would have walked away. But the epiphany I had received on Jingu Stadium’s grassy slope was still clearly etched in my mind.

In retrospect, it was only natural that I was unable to produce a good novel. It was a big mistake to assume that a guy like me who had never written anything in his life could spin off something brilliant right off the bat. I was trying to accomplish the impossible. Give up trying to write something sophisticated, I told myself. Forget all those prescriptive ideas about “the novel” and “literature” and set down your feelings and thoughts as they come to you, freely, in a way that you like.

While it was easy to talk about setting down one’s impressions freely, doing it wasn’t all that simple. For a sheer beginner like myself it was especially hard. To make a fresh start, the first thing I had to do was get rid of my stack of manuscript paper and my fountain pen. As long as they were sitting in front of me, what I was doing felt like “literature.” In their place, I pulled out my old Olivetti typewriter from the closet. Then, as an experiment, I decided to write the opening of my novel in English. Since I was willing to try anything, I figured, why not give that a shot?

Needless to say, my ability in English composition didn’t amount to much. My vocabulary was severely limited, as was my command of English syntax. I could only write in simple, short sentences. That meant that, however complex and numerous the thoughts running around my head might be, I couldn’t even attempt to set them down as they came to me. The language had to be simple, my ideas expressed in an easy-to-understand way, the descriptions stripped of all extraneous fat, the form made compact, and everything arranged to fit a container of limited size. The result was a rough, uncultivated kind of prose. As I struggled to express myself in that fashion, however, step by step, a distinctive rhythm began to take shape.

Since I was born and raised in Japan, the vocabulary and patterns of the Japanese language had filled the system that was me to bursting, like a barn crammed with livestock. When I sought to put my thoughts and feelings into words, those animals began to mill about, and the system crashed. Writing in a foreign language, with all the limitations that entailed, removed this obstacle. It also led me to discover that I could express my thoughts and feelings with a limited set of words and grammatical structures, as long as I combined them effectively and linked them together in a skillful manner. To sum up, I learned that there was no need for a lot of difficult words—I didn’t have to try to impress people with beautiful turns of phrase.

Much later, I found out that the writer Agota Kristof had written a number of wonderful novels in a style that had a very similar effect. Kristof was a Hungarian who escaped to Neuchâtel, Switzerland in 1956 during the upheaval in her native country. She had learned—been forced to learn, really—French. Yet it was through writing in that foreign language that she succeeded in developing a style that was new and uniquely hers. It featured a strong rhythm based on short sentences, diction that was never roundabout but always straightforward, and description that was apt and free of emotional baggage. Her novels were cloaked in an air of mystery that suggested important matters hidden beneath the surface. I remember feeling somehow or other nostalgic when I first encountered her work. Quite incidentally, her first novel, The Notebook, came out in 1986, just seven years after Hear the Wind Sing.

Having discovered the curious effect of composing in a foreign language, thereby acquiring a creative rhythm distinctly my own, I returned my Olivetti to the closet and once more pulled out my sheaf of manuscript paper and my fountain pen. Then I sat down and “translated” the chapter or so that I had written in English into Japanese. Well, “transplanted” might be more accurate, since it wasn’t a direct verbatim translation. In the process, inevitably, a new style of Japanese emerged. The style that would be mine. A style I myself had discovered. Now I get it, I thought. This is how I should be doing it. It was a moment of true clarity, when the scales fell from my eyes.

Some people have said, “Your work has the feel of translation.” The precise meaning of that statement escapes me, but I think it hits the mark in one way, and entirely misses it in another. Since the opening passages of my first novella were, quite literally, “translated,” the comment is not entirely wrong; yet it applies merely to the process of writing. What I was seeking by writing first in English and then “translating” into Japanese was no less than the creation of an unadorned “neutral” style that would allow me freer movement. My interest was not in creating a watered-down form of Japanese. I wanted to deploy a type of Japanese as far removed as possible from so-called literary language in order to write in my own natural voice. That required desperate measures. I would go so far as to say that, at that time, I may have regarded Japanese as no more than a functional tool.

Some of my critics saw this as a threatening affront to our national language. Language is very tough, though, a tenacity that is backed up by a long history. Its autonomy cannot be lost or seriously damaged however it is treated, even if that treatment is rather rough. It is the inherent right of all writers to experiment with the possibilities of language in every way they can imagine—without that adventurous spirit, nothing new can ever be born. My style in Japanese differs from Tanizaki’s, as it does from Kawabata’s. That is only natural. After all, I’m another guy, an independent writer named Haruki Murakami.

* * * *

It was a sunny Sunday morning in spring when I got the call from an editor at the literary journal Gunzo telling me that Hear the Wind Sing had been shortlisted for their new writers’ prize. Almost a year had passed since the season opener at Jingu Stadium, and I had turned 30. It was around 11 AM, but I was still fast asleep, having worked very late the night before. I groggily picked up the receiver, but I had no idea at first who was on the other end or what he was trying to tell me. To tell the truth, by that time I had quite forgotten that I had sent off Hear the Wind Sing to Gunzo. Once I had finished the manuscript and put it in someone else’s hands, my desire to write had altogether subsided. Composing it had been, so to speak, an act of defiance—I had written it very easily, just as it came to me—so the idea that it might make the short list had never occurred to me. In fact, I had sent them my only copy. If they hadn’t selected it, it probably would have vanished forever. (Gunzo didn’t return rejected manuscripts.) Most likely too, I would have never written another novel. Life is strange.

The editor told me that there were five finalists including me. I was surprised, but I was also very sleepy, so the reality of what had happened didn’t really sink in. I got out of bed, washed up, got dressed, and went for a walk with my wife. Just when we were passing the local elementary school, I noticed a passenger pigeon hiding in the shrubbery. When I picked it up I saw that it seemed to have a broken wing. A metal tag was affixed to its leg. I gathered it gently in my hands and carried it to the closest police station, at Aoyama-Omotesando. As I walked there along the side streets of Harajuku, the warmth of the wounded pigeon sank into my hands. I felt it quivering. That Sunday was bright and clear, and the trees, the buildings, and the shop windows sparkled beautifully in the spring sunlight.

That’s when it hit me. I was going to win the prize. And I was going to go on to become a novelist who would enjoy some degree of success. It was an audacious presumption, but I was sure at that moment that it would happen. Completely sure. Not in a theoretical way but directly and intuitively.

* * * *

I wrote Pinball, 1973 the following year as a sequel to Hear the Wind Sing. I was still running the jazz bar, which meant that Pinball was also written late at night at my kitchen table. It is with love mingled with a bit of embarrassment that I call these two works my kitchen-table novels. It was shortly after completing Pinball, 1973 that I made up my mind to become a full-time writer and we sold the business. I immediately set to work on my first full-length novel, A Wild Sheep’s Chase, which I consider to be the true beginning of my career as a novelist.

Nevertheless, these two short works played an important role in what I have accomplished. They are totally irreplaceable, much like friends from long ago. It seems unlikely that we will ever get together again, but I will never forget their friendship. They were a crucial, precious presence in my life back then. They warmed my heart, and encouraged me on my way.

I can still remember with complete clarity the way I felt when whatever it was came fluttering down into my hands that day 30 years ago on the grass behind the outfield fence at Jingu Stadium; and I recall just as clearly the warmth of the wounded pigeon I picked up in those same hands that spring afternoon a year later, near Sendagaya Elementary School. I always call up those sensations whenever I think about what it means to write a novel. Such tactile memories teach me to believe in that something I carry within me, and to dream of the possibilities it offers. How wonderful it is that those sensations still reside within me today.

________________________

The Birth of My Kitchen Table Fiction: An Introduction to WIND/PINBALL: Two Novels

Copyright 2015 © by Haruki Murakami. Translated by Ted Goossen