TORONTO – A research team out of Western University has helped find evidence of past microbial life in a German meteorite crater that they hope will help scientists find evidence of past life on Mars.

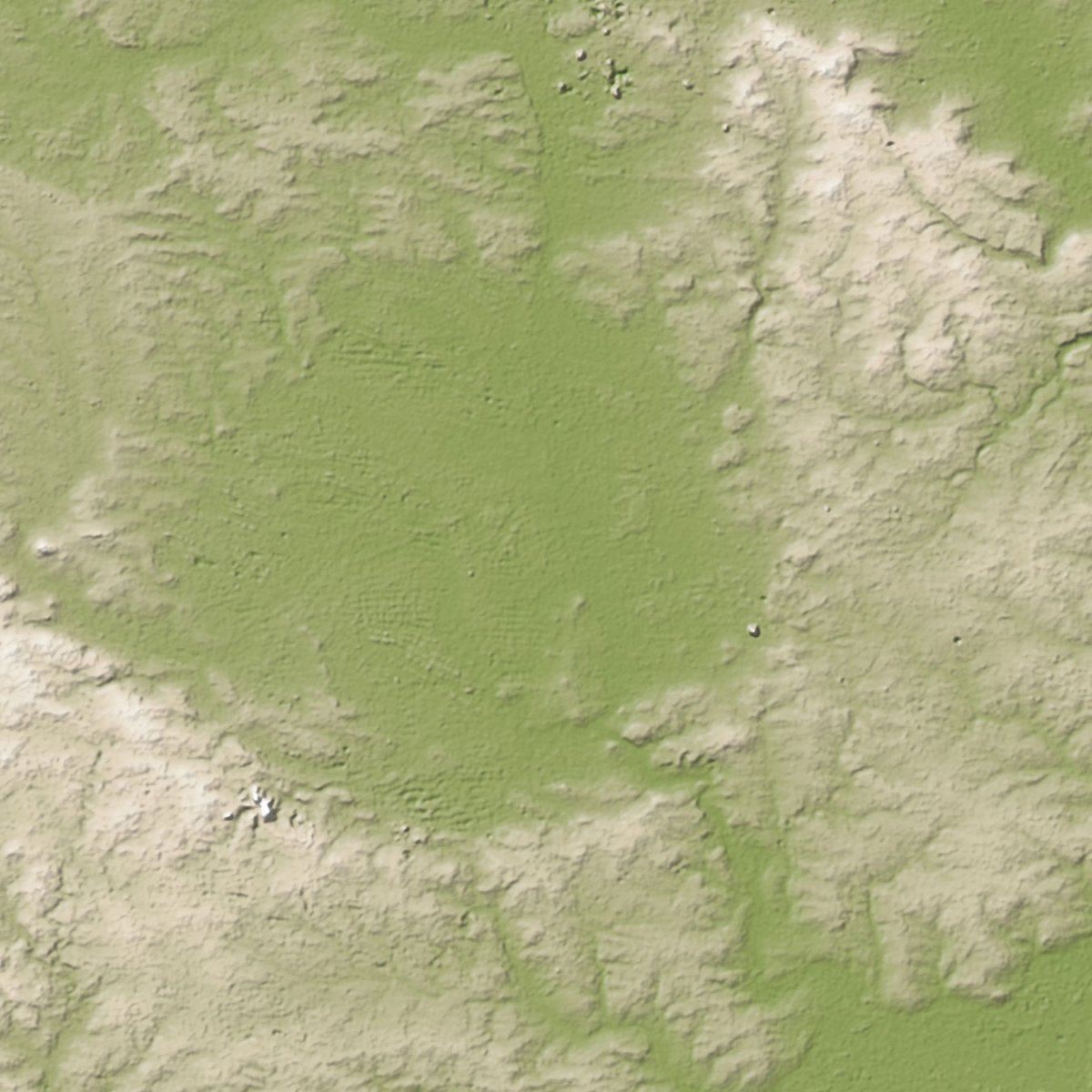

The crater, Nordlinger Ries, is about 14 million years old, relatively young when it comes to meteorite craters.

“This is like a window into what would have happened or could have happened four billion years ago on Earth,” Gordon Osinski, part of the Western research team, told Global News. Osinski is the associate director at the Centre for Planetary Science and Exploration at Western University as well as the Director of the Canadian Lunar Research Network.

“One of the issues when we talk about early life on Earth or Mars is that there are no rocks older than about four billion years on Earth,” said Osinski. “And so, we don’t know really where or when life evolved on Earth.”

When a meteorite impacts a planet or another body, extreme heat is released, creating glass. Together with water, the immediate area forms a hydrothermal system, with hot water rising to the surface and cooling, and then the colder water sinking. The area becomes very conducive to life.

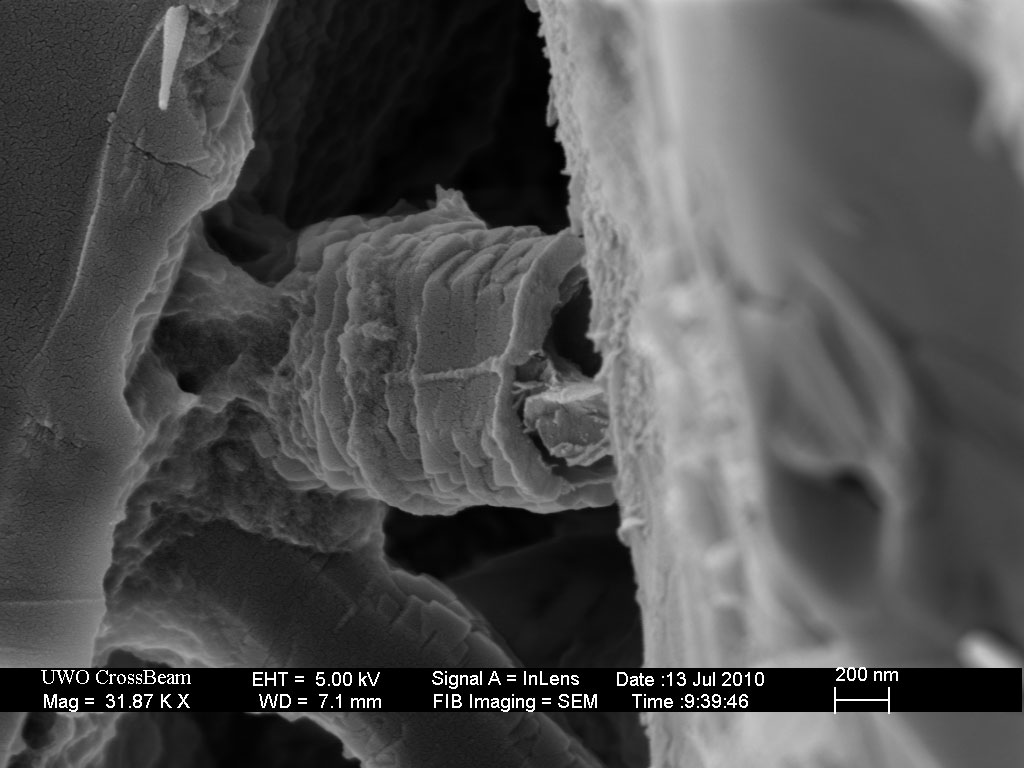

Upon studying the rocks found at Nordlinger Ries, the researchers found extremely small tubular features — about one-millionth to three-millionth of a metre in diameter. They believe that these trace fossils lived in the newly created meteorite impact glass, eating their way into the glass over hundreds of thousands, if not millions of years, leaving behind what is essentially a footprint.

“The really neat thing about impact craters is that every object in the solar system with a solid surface, whether it be ice or rock, has been struck in the past,” Osinski said. That, he said, means that Mars — believed to have once had flowing water — could have harboured similar hydrothermal systems, and therfore produced microbial life.

Osinski believes that, when most people think about impact craters, images of mass destruction are called to mind. However, the impacts can be beneficial to microbial life.

“On early Earth and Mars where they were quite inhospitable environments, these craters would have been protective little oases where life would thrive and evolve.”

“If we’re looking for life on Mars, that’s what we’re looking for.”

Using the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, they know that there are areas that hold more promise than others, mainly due to the formation of clay.

“There are a couple of craters…where there does look to be evidence for hydrothermal alteration,” said Osinski.

Though challenging to find areas that may hold the most promise for signs of hydrothermal alteration, there are some prime locations. They look for clays that on Earth need water to form.

“There’s morphological evidence for what looks like hot spring deposits,” Richard Leveille research scientist at McGill University told Global News. Leveille is also on the Mars Science Laboratory, otherwise know as Curiosity, team.

So why hasn’t Curiosity found any evidence?

“Curiosity is in a crater right now, so there is interest in finding possibly hydrothermal minerals,” said Leveille. “But the problem is, Curiosity is smack in the middle of the crater at a low elevation. And a lot of the hydrothermal systems that develop in a crater are located around the rim or near the rim of the crater, and Curiosity is never going to get there.”

Leveille said that this research is promising, and that because it’s difficult to find these trace fossils from afar, a future mission that returns some samples to Earth may need to be considered.

Comments