The stereotypical religious conservative sees social justice, at best, as a distraction from practices of piety or, at worst, a heretical deviation from the gospel. The stereotypical religious progressive sees social justice as a biblical imperative—but seems to have no time for spiritual disciplines such as prayer, meditation, and fasting. This seems to be changing as many religious conservatives increasingly speak favorably about social justice. My own research on the evangelical left (self-promotion alert: if you haven’t read Moral Minority yet, now is the time—it just came out in a much, much less expensive paperback edition) discussed many other Christians who sought to practice both social justice and a rigorous spirituality.

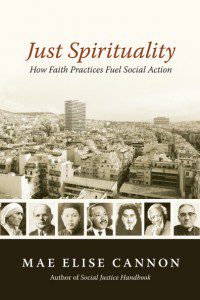

In her new book Just Spirituality: How Faith Practices Fuel Social Action, Mae Cannon, an ordained minister in the Evangelical Covenant Church and a Middle East expert for World Vision, offers half a dozen fascinating profiles of such Christians. They include:

In her new book Just Spirituality: How Faith Practices Fuel Social Action, Mae Cannon, an ordained minister in the Evangelical Covenant Church and a Middle East expert for World Vision, offers half a dozen fascinating profiles of such Christians. They include:

- Mother Teresa, whose practice of silence as a monastic inspired a lifetime of service. God spoke into her silence, which was a means of removing worldly distractions. Cannon writes that in these moments “she experienced God’s love, which compelled her to bring God’s love to the poorest of the poor.”

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, whose life of prayer led to an emphasis on discipleship and resistance to Nazi anti-Semitism. His daily exercises of prayer, according to Cannon, “built up such ingrained habits of virtue that he had the inner spiritual resources for appropriate action.”

- Martin Luther King, Jr., whose practices of beloved community and churchly accountability in Montgomery, Alabama, led to proclamations of justice. Surrounded by the historic black church, writes Richard Lischer in The Preacher King, “King gave names to what he saw: sin, racism, genocide, doom, cowardice, expediency, idolatry of nation, militarism, religious hypocrisy.”

- Fairuz, a devout Maronite Christian from Beirut whose Lebanese folk music has inspired freedom and community throughout the Middle East. Often seen kneeling in prayer at the recording studio, she sings for groups of any religion, ethnicity, and nation. Her song “Ya Zahrat al Madayn” (“Flower of the Cities”) mourns the suffering of the Arab community in Jerusalem in 1948.

- Desmond Tutu, an Anglican archbishop in South Africa, whose Sabbath-keeping led to reconciliation in the aftermath of apartheid. “All over this magnificent world God calls us to extend His kingdom of shalom—peace and wholeness—of justice, of goodness, of compassion, of caring, of sharing, of laughter, of joy, and of reconciliation. God is transfiguring the world right this very moment through us because God believes in us and because God loves us.”

In these profiles—and in Cannon’s practical advice on spiritual practices such as retreats of silence, centering, the daily examen, journaling, and Sabbath-keeping—we glimpse a powerful synthesis of the material and the mystical. Mother Teresa and Desmond Tutu were not progressive technocrats. They embodied pathos, joy, and sensitivity to the supernatural. Their implicit message, to use a Wesleyan formulation, centers on holiness: attention to the inner life (personal holiness) can reorient an outer life (social holiness) toward justice.