A new documentary, Particle Fever, achieves the almost impossible: it makes the workings of the Large Hadron Collider comprehensible – and exciting – to even the most science-phobic viewer. Mark Levinson, the film's director, first visited Cern, home of the LHC on the Swiss-French border, in 2007 and kept going back until July 2012, when the crack team of physicists concluded a two-decade quest to find the Higgs boson .

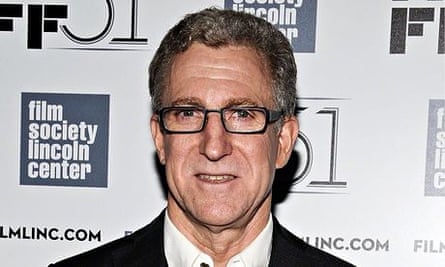

Particle Fever follows half a dozen diverse characters – out of more than 10,000 scientists from more than 100 countries – who work on the world's largest and most expensive science experiment. It shows them theorising, arguing, playing table tennis. Levinson, 59, has been a sound editor since the 1980s – notably on many of Anthony Minghella's films – but he gained a PhD in particle physics before that.

You've said you don't think Particle Fever is a science documentary. What is it then?

I think it's about man's pursuit of understanding. I wanted to make a film that would appeal to people who may not even think they were interested in science but can relate to this absolutely amazing human endeavour. The Large Hadron Collider can be hard to justify in terms of expense – but, although it may not be needed for our survival, it is something that makes us human and important.

When you started filming, did you imagine that the Cern scientists would find the Higgs particle?

No. I definitely thought there would be the Higgs or something like it, but would they find it while we were filming? I did not think that. Almost all of the physicists said that the Higgs was so hard to find that it was probably going to take years of collecting data. In fact everybody thought that if they saw something it would maybe be a new particle, but not the Higgs.

Physics appears to be a lot of staring at computer screens with numbers on them. How do you make that dramatic?

Luckily there was a lot of natural drama. We didn't have to invent it, we just had to recognise it and adapt to it as it happened. I've worked for a long time in the fiction world – I've written scripts, I directed a feature film before, but if I was scripting I don't think I could have actually done a better job in terms of creating the tension.

Are you referring to 2008, when the LHC closed down for more than a year because of a problem with the magnets?

The accident was 10 days after I started shooting. My immediate reaction was: "Oh my God, there's my film!" But I realised they'd probably get it going again and that it was a great dramatic hook. There was a lot of pressure because of the accident, so it made the next startup even more tense, and then the result, which is really a cliffhanger about what's going to happen next.

How important was your own background in physics in making the film?

Oh, it was essential, I think. I was able to jump right in and I didn't have to do research into the physics that somebody who was just starting out would have to do. In some senses, physics hadn't changed much since I got out of it in the 80s, because they didn't have the LHC. So I knew what the situation was, I knew the people, I knew what their lives were like and I already knew what the stakes were.

At the heart of the film is the odd dynamic between theoretical and experimental physicists. Can you explain?

The stereotype is the solitary theorist sitting in a room by himself like Einstein and walking up to a board occasionally. They are very mathematical, abstract and, in some senses, the elite. But they need people to design experiments for them to give them feedback and point them in the right direction. The conflict often comes between their timescales. A theorist can wake up in the morning, suddenly erase an equation and rewrite it. An experimentalist, meanwhile, has been working on building a machine for 10 years to prove that theory.

You shot more than 500 hours of footage – how did the scientists feel about you following them around all that time?

Many of them are film buffs and they loved the fact that I was a feature film-maker. They thought I was crazy shooting all this stuff but there was also the excitement that, who knows, maybe I'll introduce somebody to Nicole Kidman or something like that.

What's Cern like?

It feels very much like a university. There is probably more security than on many campuses, but once you get in, you can wander around – though there are certain places, like the underground cavern, you can't go. But most of the buildings are just open offices and then there's a first-class cafeteria with French chefs. That's a real hub, socially, but also a lot of people meet there and discuss physics while eating choucroute or fillets of fish. The French pastries are probably better than at any university I've ever been to and there's a big coffee culture.

Unusually, there's no narrator for the documentary. Why not?

We wanted it to feel like a drama, a character-based film, and if you have this omniscient narrator it just says "science documentary". So the idea was always to keep it more organic and weave it in so you almost don't realise you are being lectured in any way. It's more like personal tutoring.

There are some fantastic communicators in the film – particularly a physicist called Monica Dunford. Did you have to interview hundreds to find the people you got?

I didn't interview hundreds. Monica was in the first dozen that I interviewed and I was lucky, because it was clear straight away that she had something special. Look, it's not only in science: the majority of people are not necessarily interesting, articulate and charismatic. I don't think these were totally exceptional, but I do think we happen to have some of the best.

Women have a prominent role in the film. Is that your experience of Cern or science in general?

No, and in fact I worried that we were maybe a little too woman-heavy because it was not representative. But we went with the best characters and I'm very happy it has ended up this way, because it's so clear that women are under-represented. You can see in the bigger shots in the control rooms, there's a number of women, but it's still maybe 30%, which is really low. It would be so satisfying if the film could have an impact on that.

Now is a boom time for popular science – do you plan to continue in that area?

I was spoiled in the subject here, but it has catalysed an interest in looking at science from a storytelling perspective. There's a book I'd like to adapt next – all I'll say is it has to do with molecular biology and music. Hopefully, there continues to be a hunger for these films.

An Imax screening of Particle Fever – with Mark Levinson and Monica Dunford in conversation with broadcaster and Guardian journalist Alok Jha – takes place at the Science Museum in London on 16 April (tickets available at sciencemuseum.org.uk)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion