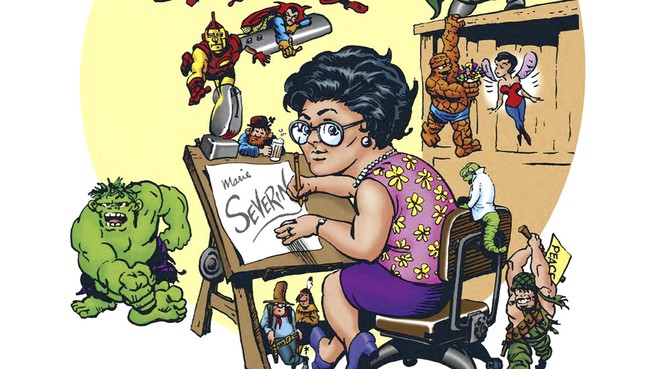

Remembering the Woman Who Changed Marvel Comics

Marie Severin, the trailblazing comic-book artist who drew some of pop culture’s most iconic characters, died Thursday at the age of 89.

After Marie Severin started at Marvel Comics in 1959, one of her first assignments was a spread that Esquire magazine commissioned on college drug culture. “They wanted Kirby,” she recalled in an interview, referring to the company’s biggest star, the penciler Jack Kirby. “[The production manager Sol Brodsky] said, ‘I don’t want to use Kirby, we’ll miss a deadline. Marie, see what they want.’”

Severin, who died on Thursday at the age of 89, was a gifted artist who had worked at the defunct EC Comics in the ’40s, coloring romance comics, horror stories, and war adventures. At Marvel, she had been tucked away in the production department until the publisher Martin Goodman noticed her work in Esquire.

“Mr. Goodman saw it and he told [the Marvel editor in chief] Stan [Lee], ‘What is she doing in the production department? Give her some art work.’ Then [Steve] Ditko quit, and there I am on Dr. Strange … I must have been worth something, they kept me on for 30 years. That’s how I got into the drawing—it had to be on a fluke.” But Severin’s skill was no fluke, and her art for titles such as Doctor Strange; The Incredible Hulk; Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner; and the parody series Not Brand Echh remains iconic to this day.

The early days of comic production were extremely crude, and far from today’s computerized process that guarantees precise detail. Severin was there from the very beginning of Marvel’s superhero boom, which relied on costumes and action sequences that popped off the page. She was adept at every part of the comic-book-illustration process, serving as Marvel’s chief colorist until 1972, when she transitioned primarily into penciling and inking, though she would still do coloring and lettering work from time to time. She helped create long-running characters such as Spider-Woman (designing her original, iconic costume), the Living Tribunal, Tigra, and the bizarre Doctor Strange villain Zom.

In the ’80s, Severin worked on Marvel’s toys and books, and stayed at the company well into the 2000s. She was inducted into the Will Eisner Comics Hall of Fame in 2001 and named a Comic-Con International Icon in 2017, in recognition of her groundbreaking contributions at a time when the comic-book industry was dominated by men.

During Severin’s tenure, Marvel’s creative staff was almost entirely male, and it was difficult for her to find her place socially within the cliquey industry. “They say that women gossip, well networking is male gossip, and they ‘networked’ all the time,” she once joked. “Sure, I’d have lunch with them once in a while, but the conversations were always male; it was just normal. So you’re sort of out of it.”

Because of Marvel’s boys’ club, Severin often went unsung, and her contributions are still less widely touted than others. But she had a deep understanding of how crucially her colorist work could affect the mood and tone of a story. “If somebody just killed somebody, disemboweled them, whatever, or if fury is building up in the story, I use deep reds and stuff like that,” she said in an interview. “It’s like music in the background. I think of coloring as the music in comic books. It gives that little oomph to it.”

Her penciling, though, was just as notable, especially compared to Marvel’s 1960s legends Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and John Romita. Her characters’ faces shone with expressive detail, and she was well known for her skill with likenesses, a challenge given the limitations of the comic-book panel.

Severin’s healthy disrespect for the genre is probably what helped keep her work so grounded, funny, and human. In recalling Not Brand Echh, the series which satirized Marvel’s brawny excesses, she said it was her favorite assignment because she was “the silliest person working on it … Really, I still can’t take superheroes that seriously, so here was my chance to get it all out.”

Even when working on psychedelic titles such as Doctor Strange, she never lost sight of the person at the center of the wild and wacky adventure she was drawing. The same goes for her work on The Incredible Hulk, which is seriously worth rereading (and available in Marvel’s digital comics service). Her illustrated guide, “How to Be a Comic Book Artist!,” in the pages of Not Brand Echh sums up her work perfectly: witty, knowing, beautifully rendered, and just a little bit macabre.