Sign up for our free Health Check email to receive exclusive analysis on the week in health Get our free Health Check email

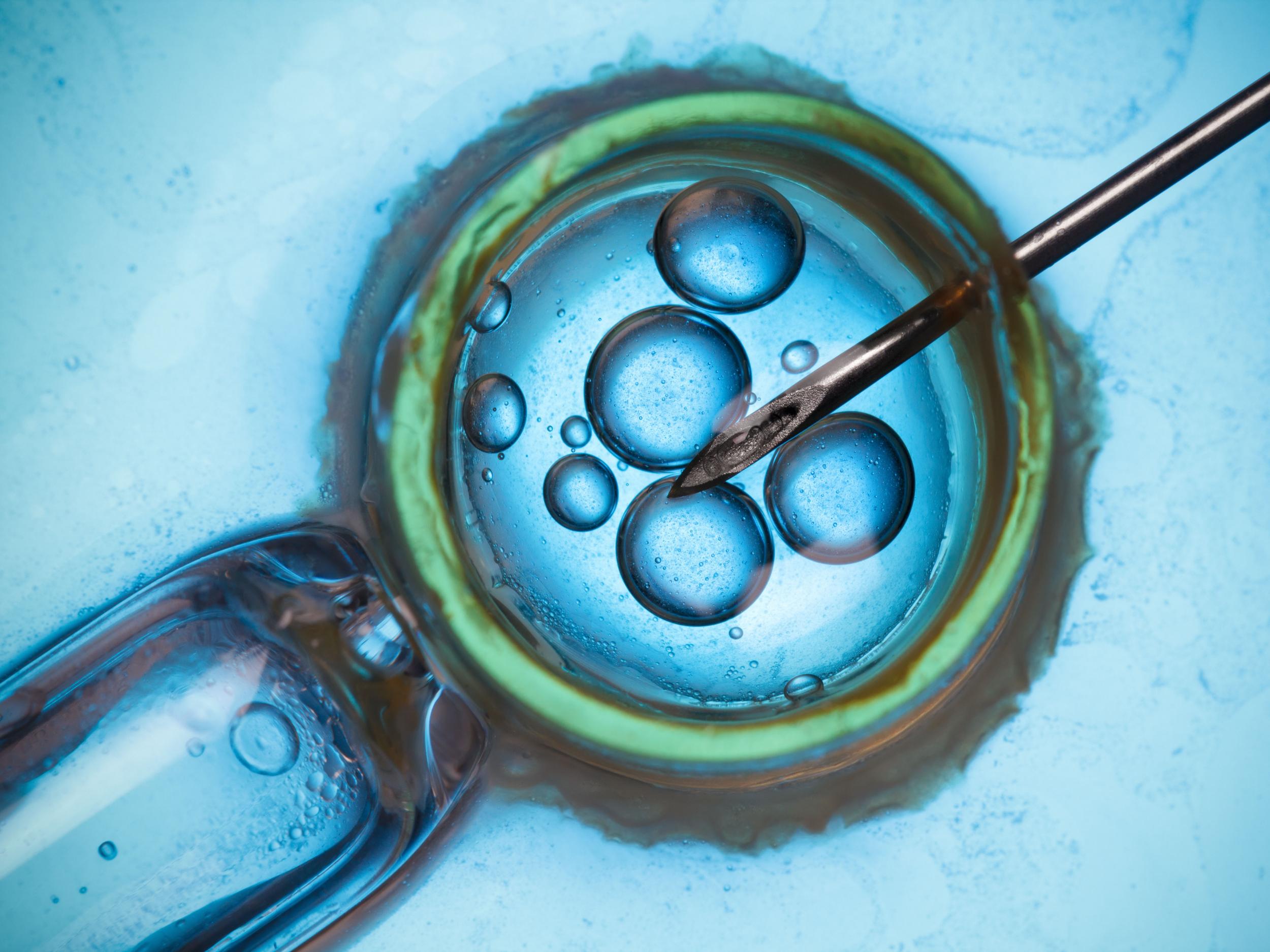

Genetic screening of embryos due to be implanted in IVF makes no difference to women’s chances of successfully having a baby, despite costing thousands of pounds at fertility clinics .

Pre-implantation genetic testing (PGT) is offered as an add-on by many UK clinics who claim it gives older women the best chance of motherhood success by screening out embryos with genetic abnormalities.

But a major international study including hundreds of women between the age of 36 and 40 found no difference in their chances of giving birth within a year after having PGT or IVF on its own.

The findings, published in the journal Human Reproduction on Sunday, confirm the beliefs of many fertility experts who say private IVF clinics often “take couples for a ride” with non-evidence based therapies.

In the wake of the research they said women should no longer be offered PGT, which costs nearly £2,000 per cycle at some prominent UK clinics.

Genetic screening takes material from eggs at the earliest stage of embryo development and tests for abnormalities in the chromosomes which carry DNA.

Humans have 23 chromosomes, and having more or fewer than this is a common issue in sex cells that gets worse with age – affecting over 50 per cent of eggs in women over 40.

These abnormalities are the main cause of miscarriage and a major reason why some embryos produced using IVF don’t lead to successful pregnancy after being transferred. PGT works on the principle that negative pregnancies and miscarriages can be minimised by screening these abnormal embryos before they’re implanted.

While NHS clinics screen for genetic diseases PGT is not routinely offered, however the increasing postcode lottery for patients as cash-strapped regions cut funding for IVF cycles means many more people use private services.

It is just one of a range of add-on (adjuvant) therapies and tests which clinics say are necessary to achieve the best results.

However The Independent has revealed how UK fertility watchdogs are highly suspicious of inflated success rates being advertised to UK couples, which some overseas groups claim are as high as 98 per cent.

“All too often couples requiring IVF treatment are taken for a ride when it comes to a bewildering array of unproven tests and adjuvant treatments,” said Professor Jan Brosens, an obstetrics and gynaecology expert at the University of Warwick, who was not involved in the study.

“This smartly designed and well conducted study was designed to give couples clear-cut information on whether PGT-A increases the chance of having a baby within one year.

“The answer is no.”

The study, which followed 396 women across nine fertility centres in seven countries, randomly allocated half the participants have either abnormality screening through PGT, or just IVF.

Show all 40 1 /40Health news in pictures Health news in pictures Coronavirus outbreak The coronavirus Covid-19 has hit the UK leading to the deaths of two people so far and prompting warnings from the Department of Health

AFP via Getty

Health news in pictures Thousands of emergency patients told to take taxi to hospital Thousands of 999 patients in England are being told to get a taxi to hospital, figures have showed. The number of patients outside London who were refused an ambulance rose by 83 per cent in the past year as demand for services grows

Getty

Health news in pictures Vape related deaths spike A vaping-related lung disease has claimed the lives of 11 people in the US in recent weeks. The US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention has more than 100 officials investigating the cause of the mystery illness, and has warned citizens against smoking e-cigarette products until more is known, particularly if modified or bought “off the street”

Getty

Health news in pictures Baldness cure looks to be a step closer Researchers in the US claim to have overcome one of the major hurdles to cultivating human follicles from stem cells. The new system allows cells to grow in a structured tuft and emerge from the skin

Sanford Burnham Preybs

Health news in pictures Two hours a week spent in nature can improve health A study in the journal Scientific Reports suggests that a dose of nature of just two hours a week is associated with better health and psychological wellbeing

Shutterstock

Health news in pictures Air pollution linked to fertility issues in women Exposure to air from traffic-clogged streets could leave women with fewer years to have children, a study has found. Italian researchers found women living in the most polluted areas were three times more likely to show signs they were running low on eggs than those who lived in cleaner surroundings, potentially triggering an earlier menopause

Getty/iStock

Health news in pictures Junk food ads could be banned before watershed Junk food adverts on TV and online could be banned before 9pm as part of Government plans to fight the "epidemic" of childhood obesity. Plans for the new watershed have been put out for public consultation in a bid to combat the growing crisis, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) said

PA

Health news in pictures Breeding with neanderthals helped humans fight diseases On migrating from Africa around 70,000 years ago, humans bumped into the neanderthals of Eurasia. While humans were weak to the diseases of the new lands, breeding with the resident neanderthals made for a better equipped immune system

PA

Health news in pictures Cancer breath test to be trialled in Britain The breath biopsy device is designed to detect cancer hallmarks in molecules exhaled by patients

Getty

Health news in pictures Average 10 year old has consumed the recommended amount of sugar for an adult By their 10th birthdy, children have on average already eaten more sugar than the recommended amount for an 18 year old. The average 10 year old consumes the equivalent to 13 sugar cubes a day, 8 more than is recommended

PA

Health news in pictures Child health experts advise switching off screens an hour before bed While there is not enough evidence of harm to recommend UK-wide limits on screen use, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health have advised that children should avoid screens for an hour before bed time to avoid disrupting their sleep

Getty

Health news in pictures Daily aspirin is unnecessary for older people in good health, study finds A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine has found that many elderly people are taking daily aspirin to little or no avail

Getty

Health news in pictures Vaping could lead to cancer, US study finds A study by the University of Minnesota's Masonic Cancer Centre has found that the carcinogenic chemicals formaldehyde, acrolein, and methylglyoxal are present in the saliva of E-cigarette users

Reuters

Health news in pictures More children are obese and diabetic There has been a 41% increase in children with type 2 diabetes since 2014, the National Paediatric Diabetes Audit has found. Obesity is a leading cause

Reuters

Health news in pictures Most child antidepressants are ineffective and can lead to suicidal thoughts The majority of antidepressants are ineffective and may be unsafe, for children and teenager with major depression, experts have warned. In what is the most comprehensive comparison of 14 commonly prescribed antidepressant drugs to date, researchers found that only one brand was more effective at relieving symptoms of depression than a placebo. Another popular drug, venlafaxine, was shown increase the risk users engaging in suicidal thoughts and attempts at suicide

Getty

Health news in pictures Gay, lesbian and bisexual adults at higher risk of heart disease, study claims Researchers at the Baptist Health South Florida Clinic in Miami focused on seven areas of controllable heart health and found these minority groups were particularly likely to be smokers and to have poorly controlled blood sugar

iStock

Health news in pictures Breakfast cereals targeted at children contain 'steadily high' sugar levels since 1992 despite producer claims A major pressure group has issued a fresh warning about perilously high amounts of sugar in breakfast cereals, specifically those designed for children, and has said that levels have barely been cut at all in the last two and a half decades

Getty

Health news in pictures Potholes are making us fat, NHS watchdog warns New guidance by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the body which determines what treatment the NHS should fund, said lax road repairs and car-dominated streets were contributing to the obesity epidemic by preventing members of the public from keeping active

PA

Health news in pictures New menopause drugs offer women relief from 'debilitating' hot flushes A new class of treatments for women going through the menopause is able to reduce numbers of debilitating hot flushes by as much as three quarters in a matter of days, a trial has found. The drug used in the trial belongs to a group known as NKB antagonists (blockers), which were developed as a treatment for schizophrenia but have been “sitting on a shelf unused”, according to Professor Waljit Dhillo, a professor of endocrinology and metabolism

REX

Health news in pictures Doctors should prescribe more antidepressants for people with mental health problems, study finds Research from Oxford University found that more than one million extra people suffering from mental health problems would benefit from being prescribed drugs and criticised “ideological” reasons doctors use to avoid doing so.

Getty

Health news in pictures Student dies of flu after NHS advice to stay at home and avoid A&E The family of a teenager who died from flu has urged people not to delay going to A&E if they are worried about their symptoms. Melissa Whiteley, an 18-year-old engineering student from Hanford in Stoke-on-Trent, fell ill at Christmas and died in hospital a month later.

Just Giving

Health news in pictures Government to review thousands of harmful vaginal mesh implants The Government has pledged to review tens of thousands of cases where women have been given harmful vaginal mesh implants.

Getty

Health news in pictures Jeremy Hunt announces 'zero suicides ambition' for the NHS The NHS will be asked to go further to prevent the deaths of patients in its care as part of a “zero suicide ambition” being launched today

Getty

Health news in pictures Human trials start with cancer treatment that primes immune system to kill off tumours Human trials have begun with a new cancer therapy that can prime the immune system to eradicate tumours. The treatment, that works similarly to a vaccine, is a combination of two existing drugs, of which tiny amounts are injected into the solid bulk of a tumour.

Nephron

Health news in pictures Babies' health suffers from being born near fracking sites, finds major study Mothers living within a kilometre of a fracking site were 25 per cent more likely to have a child born at low birth weight, which increase their chances of asthma, ADHD and other issues

Getty

Health news in pictures NHS reviewing thousands of cervical cancer smear tests after women wrongly given all-clear Thousands of cervical cancer screening results are under review after failings at a laboratory meant some women were incorrectly given the all-clear. A number of women have already been told to contact their doctors following the identification of “procedural issues” in the service provided by Pathology First Laboratory.

Rex

Health news in pictures Potential key to halting breast cancer's spread discovered by scientists Most breast cancer patients do not die from their initial tumour, but from secondary malignant growths (metastases), where cancer cells are able to enter the blood and survive to invade new sites. Asparagine, a molecule named after asparagus where it was first identified in high quantities, has now been shown to be an essential ingredient for tumour cells to gain these migratory properties.

Getty

Health news in pictures NHS nursing vacancies at record high with more than 34,000 roles advertised A record number of nursing and midwifery positions are currently being advertised by the NHS, with more than 34,000 positions currently vacant, according to the latest data. Demand for nurses was 19 per cent higher between July and September 2017 than the same period two years ago.

REX

Health news in pictures Cannabis extract could provide ‘new class of treatment’ for psychosis CBD has a broadly opposite effect to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main active component in cannabis and the substance that causes paranoia and anxiety.

Getty

Health news in pictures Over 75,000 sign petition calling for Richard Branson's Virgin Care to hand settlement money back to NHS Mr Branson’s company sued the NHS last year after it lost out on an £82m contract to provide children’s health services across Surrey, citing concerns over “serious flaws” in the way the contract was awarded

PA

Health news in pictures More than 700 fewer nurses training in England in first year after NHS bursary scrapped The numbers of people accepted to study nursing in England fell 3 per cent in 2017, while the numbers accepted in Wales and Scotland, where the bursaries were kept, increased 8.4 per cent and 8 per cent respectively

Getty

Health news in pictures Landmark study links Tory austerity to 120,000 deaths The paper found that there were 45,000 more deaths in the first four years of Tory-led efficiencies than would have been expected if funding had stayed at pre-election levels. On this trajectory that could rise to nearly 200,000 excess deaths by the end of 2020, even with the extra funding that has been earmarked for public sector services this year.

Reuters

Health news in pictures Long commutes carry health risks Hours of commuting may be mind-numbingly dull, but new research shows that it might also be having an adverse effect on both your health and performance at work. Longer commutes also appear to have a significant impact on mental wellbeing, with those commuting longer 33 per cent more likely to suffer from depression

Shutterstock

Health news in pictures You cannot be fit and fat It is not possible to be overweight and healthy, a major new study has concluded. The study of 3.5 million Britons found that even “metabolically healthy” obese people are still at a higher risk of heart disease or a stroke than those with a normal weight range

Getty

Health news in pictures Sleep deprivation When you feel particularly exhausted, it can definitely feel like you are also lacking in brain capacity. Now, a new study has suggested this could be because chronic sleep deprivation can actually cause the brain to eat itself

Shutterstock

Health news in pictures Exercise classes offering 45 minute naps launch David Lloyd Gyms have launched a new health and fitness class which is essentially a bunch of people taking a nap for 45 minutes. The fitness group was spurred to launch the ‘napercise’ class after research revealed 86 per cent of parents said they were fatigued. The class is therefore predominantly aimed at parents but you actually do not have to have children to take part

Getty

Health news in pictures 'Fundamental right to health' to be axed after Brexit, lawyers warn Tobacco and alcohol companies could win more easily in court cases such as the recent battle over plain cigarette packaging if the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is abandoned, a barrister and public health professor have said

Getty

Health news in pictures 'Thousands dying' due to fear over non-existent statin side-effects A major new study into the side effects of the cholesterol-lowering medicine suggests common symptoms such as muscle pain and weakness are not caused by the drugs themselves

Getty

Health news in pictures Babies born to fathers aged under 25 have higher risk of autism New research has found that babies born to fathers under the age of 25 or over 51 are at higher risk of developing autism and other social disorders. The study, conducted by the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at Mount Sinai, found that these children are actually more advanced than their peers as infants, but then fall behind by the time they hit their teenage years

Getty

Health news in pictures Cycling to work ‘could halve risk of cancer and heart disease’ Commuters who swap their car or bus pass for a bike could cut their risk of developing heart disease and cancer by almost half, new research suggests – but campaigners have warned there is still an “urgent need” to improve road conditions for cyclists. Cycling to work is linked to a lower risk of developing cancer by 45 per cent and cardiovascular disease by 46 per cent, according to a study of a quarter of a million people. Walking to work also brought health benefits, the University of Glasgow researchers found, but not to the same degree as cycling.

Getty

The number of women who had a live birth within 12 months of the study was identical in both groups, at 24 per cent. It did find that women who had PGT screening were significantly less likely to have a miscarriage and this may be enough to sway some couples.

“Many IVF clinics may well erroneously seize this as a ‘selling point’ for PGT-A,” said professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Southampton, Ying Cheong, who was not involved in the study.

“It needs to be emphasised that these are secondary end-points which the study was not powered to definitively answer and so must be interpreted with caution.

She said biopsies of embryos for PGT if there was no evidence it worked “is poor clinical practice”, adding: “We still do not understand fully the developmental biology of the egg and the embryo, and as such, may cause more harm than good.

“For these reasons, it is my opinion that PGT-A should not be offered to women with advanced maternal age.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies