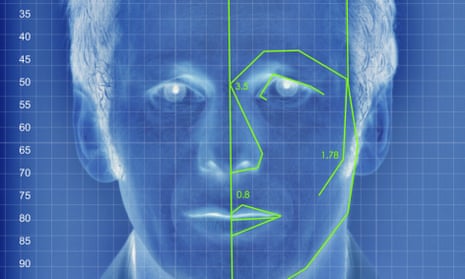

Half of all American adults are included in databases police use to identify citizens with facial recognition technology, according to new research that raises serious concerns about privacy violations and the widespread use of racially biased surveillance technology.

A report from Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy and Technology found that more than 117 million adults are captured in a “virtual, perpetual lineup”, which means law enforcement offices across the US can scan their photos and use unregulated software to track law-abiding citizens in government datasets.

Numerous major police departments have “real-time face recognition” technology that allows surveillance cameras to scan the faces of pedestrians walking down the street, the report found. In Maryland, police have been using software to identify faces in protest photos and match them to people with warrants, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The report’s findings, along with revelations from the ACLU on police monitoring in Baltimore, suggest that the technology may be violating the rights of millions of Americans and is disproportionately affecting communities of color, advocates said.

“Face recognition, when it’s used most aggressively, can change the nature of public spaces,” said Alvaro Bedoya, executive director of Georgetown’s privacy and technology center. “It can change the basic freedom we have to go about our lives without people identifying us from afar and in secret.”

The center’s year-long investigation, based on more than 100 police records requests, has produced the most comprehensive survey of facial databases to date and raises numerous questions about the lack of transparency and privacy protections.

Law enforcement biometric databases have traditionally captured DNA profiles related to criminal arrests or forensic investigations. What’s alarming about the FBI’s “face recognition unit”, according to the report, is that it is “overwhelmingly made up of non-criminal entries”.

The FBI database photos come from state driver’s licenses, passports and visa applications, meaning police can easily identify and monitor people who haven’t had any run-ins with the law.

“In the case of face recognition, there appear to be very few controls or safeguards to ensure it’s not used in situations in which people are engaged in first amendment activity,” said Neema Singh Guliani, ACLU’s legislative counsel.

The ACLU recently found that police in Baltimore may have used the recognition technology along with social media accounts to identify and arrest people with outstanding warrants during high-profile police protests last year. That alleged surveillance relied on tools from Geofeedia, a controversial social media monitoring company that partners with police.

The ACLU, which on Tuesday urged the US Department of Justice to investigate facial recognition, also revealed last week that Facebook and Twitter had provided users’ data to Geofeedia, with records suggesting that the social media sites had aided police in surveillance of protesters. The firms have since cut off Geofeedia’s special access to their data.

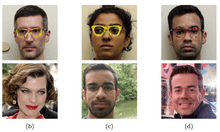

In addition to concerns about illegal monitoring and the targeting of lawful protesters, research has found that the facial recognition algorithms can be biased and inaccurate – with serious consequences for innocent people.

“This technology is powerful, but it is not neutral,” said Bedoya. “This technology makes mistakes.”

The FBI’s own statistics suggest that one out of every seven searches of its facial recognition database fails to turn up a correct match, meaning the software occasionally produces 50 “potential” matches who are all “innocent”, the report said.

Additionally, a 2012 study co-authored by an FBI expert found that leading facial recognition algorithms were up to 10% less accurate for African Americans compared with white people, the ACLU noted.

What’s more, the flawed algorithms can amplify biased policing practices since they rely on mugshot databases that disproportionately represent people of color.

For example, the Maricopa County sheriff’s office in Arizona arrests black residents at a rate three times higher than their share of the state population, and a federal judge found that police have racially profiled Latinos.

Those disparities feed into the databases, and Arizona has no law restricting police use of facial recognition, according to the ACLU. The Maricopa sheriff’s system does not even require an officer to have reasonable suspicion of a crime before searching a face in the database.

In Baltimore, some policing strategies have resulted in tens of thousands of arrests for minor offenses, with prosecutors ultimately dropping the cases.

That means many people, the vast majority of whom are people of color, may remain in facial databases even if they weren’t charged, said David Rocah, senior staff attorney with the ACLU of Maryland.

“A great many of those folks ... never should’ve been arrested in the first place and were innocent of any wrongdoing.”

Advocates are “playing catch up” with the technology, which has rolled out across the US with little oversight or restriction, Guliani said. “That’s really a backwards way to approach it … This is already being used against communities it’s designed to protect.”

Baltimore and Maricopa police officials did not respond to requests for comment.

Stephen Moyer, secretary of the Maryland department of public safety and correctional services, which operates the state’s facial recognition database, defended police use of the software, saying in a statement: “Maryland law enforcement agencies make use of all legally available technology to aggressively pursue all criminals.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion