Precious Memories

Dementia has taken its toll on former North Carolina coach Dean Smith, but family and devoted friends stand by the beloved coach.

Editor's note: Dean Smith died Saturday at the age of 83. This story about the toll dementia took on the legendary former North Carolina coach was originally posted on March 5, 2014.

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. -- Dean Smith doesn't watch the games anymore. The motion on the screen is too hard to follow. Now he thumbs through golf magazines and picture books. Most of the books are about North Carolina basketball. They seem to make him happy. He turns the pages past photo after photo of himself. Nobody knows if he knows who he is.

Music seems to make him happy, too. About a year and a half ago, a friend named Billy Barnes came over to the house to play guitar and sing a few songs. Barnes played old Baptist hymns and barbershop quartet tunes -- Daisy Daisy, give me your answer true. Music he knew Dean liked. But nothing seemed to get through. Dean was getting restless. Barnes asked if he could play one more song.

After every basketball game, win or lose, the UNC band plays the alma mater and fight song. The Carolina people stand and sing. Barnes knew Dean had heard the song thousands of times. He started to play.

Dean jumped to his feet. He waved at his wife, Linnea, to stand with him. He put his hand over his heart and sang from memory:

Hark the sound of Tar Heel voices

Ringing clear and true.

Singing Carolina's praises,

Shouting N-C-U.

Hail to the brightest star of all

Clear its radiance shine

Carolina priceless gem,

Receive all praises thine.

I'm a Tar Heel born, I'm a Tar Heel bred, and when I die I'm a Tar Heel dead!

So it's rah-rah Car'lina-lina, rah-rah Car'lina-lina, rah-rah Carolina, rah, rah, rah!

"It was just pure joy. That uninhibited joy in the music," Linnea says. "It's one of those moments that you know there's more there, or momentarily there, than sometimes you're aware of."

This is what she hopes for now. A moment of joy. A moment of connection. A moment when Dean Smith is still there.

Dementia has attacked the memory of legendary coach Dean Smith, but the memories he created will stand the test of time. Gene Wojciechowski takes a look back at some of the greatest moments from a Hall of Fame career.

WHY DO WE CARE about sports to begin with? Why do we watch? Maybe this: to connect. In the arena, or in a sports bar, or maybe just alone on your couch, you watch your favorite team and you plug into something bigger than yourself. It's a hedge against the coldness of the world. Heaven is other people.

For 36 years as the Tar Heels' head coach, Dean Smith built a family. He created a shared identity for the legions of UNC fans who still buy the tickets and wear the T-shirts and paint their dens Carolina blue. His teams won 20 or more games for 27 years in a row. But more than that, they won with a selfless style. Dean's most lasting invention was his simplest: When you make a basket, you point to the player who threw the pass. He taught his team, and those who watched, that everyone is connected.

Inside the big Carolina family, he built a smaller family -- the players and coaches and staffers who came to see him as a teacher, a guru, a role model, a surrogate dad. They asked his advice on everything from sneaker contracts to marriages. He called on their birthdays and got tickets for their in-laws. He built lifelong bonds.

But for the past seven years, maybe more, dementia has drawn the curtains closed on Dean Smith's mind. Now he is 83 and almost no light gets out. He has gone from forgetting names to not recognizing faces to often looking at his friends and loved ones with empty stares.

Here is the special cruelty of it: The connector has become disconnected. The man who held the family together has broken off and drifted away. He is a ghost in clothes, dimmed by a disease that has no cure. Even the people closest to him sometimes slip into the past tense: Coach Smith was. They can't help it. They honor him with what amounts to an open-ended eulogy. At the same time, they keep looking for a crack in the curtains. They do what people do when faced with the longest goodbye. They do the best they can.

Three times a week, a caregiver wheels Dean Smith into the Dean Smith Center. He still has a little office in the arena built in his name. Linnea thinks the routine is good for him. Linda Woods, his administrative assistant since 1977, answers his calls and checks his mail. She writes back I'm sorry to autograph seekers. Woods is retired except for Dean. When he's there, she's there. Dean often eats lunch at the office. He loved the double BLTs from down the road at Merritt's Store & Grill. But these days he eats soft things in small pieces. On the good days, he feeds himself.

When he coached, his office was a disaster: "I had files," Woods says, "and he had piles." Now it's mostly the golf magazines and the picture books. Woods turns the pages with him. You played that course with your friends, she'll say. Or: Look at all that dark hair you had on your head.

She never asks if he remembers.

Dementia steals memory, and here's another twist of the knife: Dean's memory might have been the most impressive thing about him. It was astonishing, like a magic trick. Dave Hanners, who played and coached under Dean, was going through old game films one morning in 1989 -- Dean had decided to send his former players tapes of their best games as gifts. Hanners was watching a game against Notre Dame when Dean walked by and glanced at the screen. A few seconds later, he said: Watch this next play. Yogi Poteet is going to get a backdoor pass from Billy Cunningham and score. Next time down, they switch places. Yogi's going to throw the pass and Billy will score. They watched together, and it played out exactly as Dean said.

When did you watch this film last? Hanners said.

Oh, I guess when we looked at it the day after the game, Dean said.

The game was from 1963.

No one knows what's still in there. Does he remember the numbers: 879 wins as UNC's head coach, 13 ACC tournament championships, 11 Final Fours, two national titles, an Olympic gold medal-winning team? Does he remember the moments: Michael Jordan's jumper to beat Georgetown; Michigan's Chris Webber calling a timeout he didn't have; those heartbroken students pressed against the windows when he announced his retirement in 1997? Does he remember the players: Jordan and James Worthy and Sam Perkins and Brad Daugherty and Kenny Smith and Bob McAdoo and Phil Ford and Walter Davis and Bobby Jones and Larry Brown? Does he remember coming back from eight down with 17 seconds left against Duke?

Does he remember Duke?

More than 5 million Americans have Alzheimer's, and another million-plus have other forms of dementia. (Another college basketball icon, Pat Summitt -- who set the NCAA wins record of 1,098 as the women's coach at Tennessee -- was diagnosed with early onset dementia, Alzheimer's type, at age 59 in 2011.) It's a tragedy and a mystery for every family that watches a loved one fade away. Linnea Smith, a psychiatrist, describes her husband's condition in clinical terms: neurocognitive disorder with multiple etiologies. That means it includes elements of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's disease, vascular dementia and the normal decline of old age.

She also describes it in two simpler words: relentless loss.

Chapter 1

text

Dean Smith cuts down the net after UNC beat Georgetown for his first national title in 1982. Barb Fordham, a family friend, remembers a big party in a hotel suite afterward; Dean was sitting by himself, watching a replay of the game. Pete Leabo/AP Images

BILL GUTHRIDGE, his oldest friend, has the office next door. They've known each other 60-some years; in the early '50s, when Dean was a backup guard at Kansas, he briefly dated Guthridge's sister. Dean followed Guthridge's coaching career, and in 1967 he hired Guthridge from Kansas State. Over the years, Coach Gut had regular offers to be the head man somewhere else. He got on a plane once to take the job at Penn State, but changed his mind on the layover. He ended up spending 30 years in UNC's second chair. When Dean decided to quit in '97, he didn't announce it until October -- way too late for the athletic department to hire anybody but the man waiting there on the bench. Guthridge coached three years and took the Tar Heels to two Final Fours. Then he retired, too. He got his taste.

Guthridge could deal with Dean's irritability, his need to control the smallest things. Hanners remembers Guthridge getting behind the wheel to drive them across town to lunch and Dean starting in before he could crank the car: Which route are you taking? Where are you turning off? Do you know the best way? Guthridge would glance over and say: Well, Coach Smith, I thought I'd go through Mebane. (Mebane being about 20 miles from Chapel Hill.) They squabbled and picked and laughed and talked for all those years. They sat side by side on the bench and now side by side in their little offices. There is one difference now. When Dean comes in, Guthridge slips away.

"It's something that I have learned to stay away from," he says. "Because it breaks my heart."

Every so often, Roy Williams walks over from the big office around the corner to check on Dean. Williams played on the freshman team at UNC, kept practice stats for Dean, taught at his summer camps. He was a high school coach with a losing record when Dean offered him a job as a part-time assistant in 1978 for $2,700 a year. Williams drove all over the state selling UNC calendars until he got full-time pay. He stayed 10 years, left to be head coach at Kansas, shocked the Carolina family by turning down the job when Coach Gut retired, then took it when UNC called again in 2003.

In the space of two sentences, he calls Dean an icon and a hero. He still remembers the night before he left for Kansas, dinner at the Smith house, Dean pulling him aside and saying: Just be yourself. You don't have to be anybody else. You're good enough. And don't take the losses so hard.

He still takes the losses hard. His sister died of complications from Alzheimer's. Now he sees what happened to her happening to Dean.

"It's hard to see him," Williams says. "Because I want to remember the '70s, '80s, '90s and early 2000s. That's what I want to remember."

Dean sometimes thought he retired too early. Linnea, who once wrote an academic paper on post-retirement depression, worried he would mope. But he enjoyed those first years away from the sideline. He spent more time with his kids -- he has five grown children (three from his first marriage, two with Linnea) and six grandchildren. He watched the Tar Heels as a fan, his heart pounding in a way it never did on the court. He took detailed notes on every game. He never shared the notes unless he was asked, but if somebody asked, he was thrilled. Sometimes Williams would ask Dean to draw up a play or two. It didn't hurt to have an unpaid assistant who retired as the winningest men's coach in college basketball history.

He had always made time for someone in the inner circle -- he would stop an interview or usher out a guest if a former player was on the phone. But now he really had time to talk.

"Then I noticed one day," Woods says, "that he was starting to forget some of their names."

Looking back, Linnea thinks Dean's memory started to erode in 2005 or 2006. But everybody in the Carolina family noticed after he had knee replacement surgery in 2007. He had a bad reaction to the anesthesia. He went home but then had to go back in the hospital. When he finally came out, he was disoriented. He would see a former player he'd known for years, and, instead of calling him by name, he'd nod and say: Young man.

One day he drove to the Smith Center, and instead of parking in his normal space, he left his car on the patio of the Rams Club building next door. "It's hard to get a car over there," Linda Woods says. That was about the end of his driving.

Now a specially equipped van takes him around in his wheelchair. Not long ago, Woods was helping strap him in the van so he could go back home. She felt a tap on her shoulder: "I looked up and Coach Smith had the biggest smile on his face. I hadn't seen that smile in a long time. That was the reward for my whole week."

Woods says Phil Ford visits more than anybody else. Michael Jordan is the greatest player to come from UNC. But the greatest player as a Tar Heel -- and still the most beloved -- is Phil Ford. He made first-team All-America three times as Dean's point guard from 1974 to 1978. He finished as UNC's all-time leading scorer and even now ranks second, behind Tyler Hansbrough. (Jordan is 12th.) Ford ran the Four Corners offense, the delay game that iced Carolina wins and led to the shot clock in college ball. It was Dean's highest tribute -- control of the team on the floor. After Ford's NBA career, Dean hired him as an assistant. And in the '90s, when Ford picked up two DUIs and admitted he was an alcoholic, Dean memorized Alcoholics Anonymous' 12 steps so he could help Ford get sober.

Ford still lives in the area and has a son at UNC. So he comes by a lot to sit with Dean. "He knows I'm there somewhere," Ford says. "Sometimes you can see in his eyes, he's so close to coming back. Somewhere in the back of my heart, I believe it."

Ford brings up old games, and every once in a while, Dean will smile. Sometimes they just sit there in silence.

LORD, HOW THE other schools hated him. St. Dean, they called him. Fans of the other ACC teams united under the ABC banner: Anybody But Carolina. When the NCAA tournament came around, schools around the country crowded into the tent. Someone in every group had a Dean impression, that accent as dry and flat as the Kansas prairie: It might have looked like luck to you, but we practice making those 40-footers off the backboard. That's the Carolina Way.

They grumbled about how Dean subtly baited the refs, how he planted seeds with the media that other teams played dirty. They were furious when he pulled out the Four Corners and stalled his way to a win. They couldn't stand how he acted all humble but still gave off that whiff of we're-better-than-you. They smelled it everywhere. One year the Heels beat Wake Forest after a five-second call when Wake couldn't get the ball in bounds. "We did play six seconds of good defense there," Dean said after the game. See, the ABCers said. Even when he won, a little dig.

When Mike Krzyzewski took over at Duke in 1980, he challenged Dean like no one else had. At Duke in '84, Dean sent a sub to the scorer's table, but the horn didn't sound at the next break, and the refs didn't wave the sub in. Dean ran down to the table and tried to sound the horn himself. Instead he banged the scoring button, and 20 points popped up on the Tar Heels' side of the scoreboard. The Duke fans went nuts. Dean somehow avoided a technical. Carolina won. Afterward, Krzyzewski complained about "the double standard that exists in this league."

There was also a double standard in Dean's head. He preached process instead of winning and losing. But it was easy to say that when he recruited so many great players that winning was a natural byproduct. The process worked so well, it hid the coal of desire that burned in his gut.

"Was Michael Jordan competitive on the court?" Dave Hanners says. "That's how competitive coach Smith was. People just didn't see it in the same way."

Now, as Dean has declined, the bitterness among his rivals has melted. When Lefty Driesell was at Maryland, he wrote Dean a letter to inform him they wouldn't be shaking hands after games anymore. Now Driesell frequently calls to check in. In June 2011, Krzyzewski and Dean were co-winners of the Naismith Good Sportsmanship Award. Krzyzewski keeps a photo in his office of the two of them sitting together at the ceremony in Raleigh. He told The Charlotte Observer last year: "I felt it was like two generals now at peace."

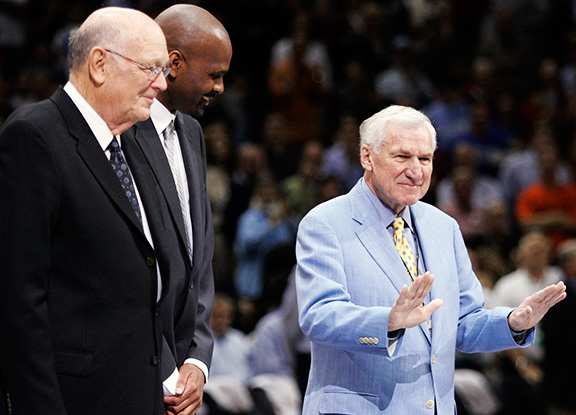

In 2008, Smith was inducted as an ACC Tournament Legend at that year's tournament in Charlotte. In the center is former Miami star Tim James. At left is Lefty Driesell, former coach at Davidson and Maryland. Steve Helber/AP Images

HE CAME OUT onto the court one last time. It was 2010, and UNC had put together an alumni game as part of the celebration of 100 years of Tar Heel basketball. They planned to honor Dean at halftime. They didn't tell him. They worried he wouldn't show if they did.

There was a full house at the Dean Dome. At halftime, a tribute video played on the big screens. Dean couldn't see it. He was down in the tunnel with Williams, Guthridge and Eddie Fogler -- his assistants on that championship team from '82. They had told him they'd walk onto the court together as part of the ceremony. He could hear an announcer, and cheers. But in the tunnel, the sound was muffled.

What are they talking about out there? he asked.

Well, they're talking about North Carolina basketball, Williams said. You and North Carolina basketball.

Can't we just go stand out there now?

Wait just a second, Coach. Just a second.

The video ended and Williams, Guthridge and Fogler led Dean onto the court. Just as they got to the center, the three assistants stepped back. Dean stood alone in the light.

Then his old players surrounded him. They hugged him and shook his hand and cried. Bobby Jones, who played for Dean in the early '70s and went on to be an NBA All-Star, wasn't sure Dean would remember him. "So I just said, 'Coach, it's Bobby Jones. Thanks for all you've done for me. We all love you.' He looked up. I could tell he certainly recognized me, and said 'Hey, Bobby.' That was a good feeling."

The players lingered. The fans would not stop cheering. Dean waved to the crowd but did not speak. Then he walked back into the tunnel.

THERE ARE STILL MOMENTS. Dean works out three times a week with exercise physiologist Kevin Kirk at Functional Fitness in Chapel Hill. Once he entered middle age, Dean didn't exercise much; for years he lived on pot roast and cigarettes and the occasional scotch. So he wasn't happy about the workouts. Sometimes he'll do a few leg presses and stretch the exercise bands. Other times Kirk just helps him flex his arms and legs.

One day they were working with a rubber ball about the size of a volleyball. Kirk stood a few feet from Dean and they bounced it back and forth a while. Then Kirk noticed Dean was glaring at him, and pointing to a spot a few feet away.

Kirk moved over there. Dean bounced him the ball. Dean pointed him to another spot, and another.

It took a minute for Kirk to catch on. Then it hit him: We're running a drill. I'm running a drill with Dean Smith. I'm on his team.

There is no way to tell when the curtain will part. There is no way to know what you will remember. You can only hope for moments worth remembering.

Kirk hustled around the floor, at Dean Smith's direction, and the old coach passed him the ball.

LAST YEAR, AFTER A FAN nominated Dean for the Presidential Medal of Freedom -- the nation's highest civilian honor -- UNC officials lobbied Washington to make sure he got it. The president can award the medal to people who, among other things, "have made especially meritorious contributions ... to cultural or other significant public or private endeavors." Dean had a case beyond the wins and the titles. Ninety-six percent of his lettermen graduated. Dean was active in politics -- he fought for a nuclear freeze and against the death penalty. And he nudged his part of the world forward when it came to race.

In the late '50s, Dean and Bob Seymour -- his pastor at Binkley Baptist Church -- took a black theology student to Chapel Hill's finest restaurant, a segregated place called The Pines. Dean was just an assistant coach then, but the managers knew him -- the Tar Heels ate team meals there. None of the staff said a word. The three men sat down and ate dinner.

Dean also recruited Charles Scott. Among UNC players, Jordan is the best and Phil Ford is the most beloved, but Scott is the most important. He came to campus in 1966 as UNC's first black scholarship athlete. He became the ACC's first black star. The maddest anybody remembers seeing Dean was a night at South Carolina when a fan called Scott a "black baboon." Dean headed into the stands before a coach pulled him back. All the way through college, and all the way through Scott's 10-year pro basketball career, fans and writers called him Charlie. He always preferred Charles. Dean called him Charles.

"He is basically the cornerstone of how I measure myself," Scott says. "To give you a story about what he has done is to give you the outline of my life."

These days Scott lives in Columbus, Ohio, where his son Shannon is a junior guard for Ohio State. His son's full name is Shannon Dean Scott.

The Medal of Freedom ceremony was at the White House in November. The 16 honorees ranged from two Nobel Prize winners to Loretta Lynn and Oprah. President Barack Obama noted that Dean couldn't come "due to an illness that he's facing with extraordinary courage." (He also brought up the old line that Dean was the only man in history who held Michael Jordan under 20 points a game.) Linnea took Dean's place, sitting next to Gloria Steinem on the stage, and accepted the medal and a hug from the president. She and Dean had been to the White House before, back in '98, when the Clintons held a state dinner for President Kim Dae-jung of South Korea. Kim's son was a Tar Heels fan.

Chapter 2

text

UNC fans still remember this 2007 celebration of the Tar Heels' 1993 championship team as the night Michael Jordan kissed Smith's head. Grant Halverson/Getty Images

THEY MAKE SURE the house is full of music. The satellite radio is tuned to the big-band and jazz stations. Linnea has a stash of videos of old variety shows with Sinatra and Dean Martin. One time a couple of the kids came by with an iPod and stuck the earbuds in his ears. He grinned and belted "Satin Doll" while they wheeled him around outside. Linnea brought in a concert harpist. A music therapist got Dean singing the old Wilbert Harrison number "Kansas City." Dean spent part of his childhood in Topeka, so they changed the lyrics: I'm goin' to Topeka, Kansas / Topeka, Kansas here I come. He rarely sings now. But music still seems to be the best connection. So they keep trying to connect.

It's a simple routine most weeks: office, church, exercise, home. Dean and Linnea live on a quiet wooded lot just outside town. Nothing says a basketball coach lives here. Dean didn't keep much memorabilia, and he gave most of it to the university after he retired. The paintings in the living room are landscapes. The books are theology and philosophy. The back deck looks down a slope to a creek. Dean used to grill steaks out on the deck for the parents of recruits. Linnea marveled at how he got them just the right doneness and always remembered who wanted what.

Two dogs have the run of the house -- a wary goldendoodle named Lila and a sweet Chinese crested named Eddie. Dean tolerates them. He was never much for froufrou dogs. He loved his two big dogs, a golden retriever named Mayzie and a black mixed named Kona. He'd walk them all over the property. Now they're buried out back.

He played golf for years with three of his closest friends: Chris Fordham, who joined the medical school faculty the same year Dean arrived and who later became chancellor; Simon Terrell, who ran high school sports in North Carolina; and Earl Somers, a Chapel Hill psychiatrist. They played from Hilton Head to Pebble Beach, and once went to Scotland to play Muirfield. The other three are gone now; Fordham, the last, died in 2008. By then, Dean wasn't playing golf anymore.

Linnea wishes she could know for sure if the trips to the office and the Sundays in church are doing any good. She wishes she and Dean had been able to talk it through. There was no way to prepare. Nobody knew until it had already happened.

"If you have cancer," she says, "you can process it and come to resolution in areas that you need to, or make sense or meaning of your life, and meaning of what's going on, and express your wishes."

She looks out the window.

"And we didn't have that."

The phone rings every few minutes. Linnea lets it ring. There hasn't been much new to say lately. There's no cure for dementia. But people keep calling, checking, hoping. "I'm sure they think," Linnea says, "is this going to be the last time? Is this my goodbye?"

She wonders the same thing, of course. People can live with dementia for decades. They also can die from complications out of the blue. In between, most of the time, there is a vast and disconnected space. But the ones who care about Dean work for those few brief moments of connection, a smile or a song or a bouncing ball.

The dogs start barking. The door opens. And there he is.

The caregiver wheels him in. Dean is back from his trip to the office. He is wearing a white UNC ball cap and a Carolina blue windbreaker. His chin rests on his chest, and his eyes are closed.

Linnea will turn on some music later, to see if it connects. But for now the house is quiet. The caregiver wheels him around the corner, out of sight.

Tommy Tomlinson is a writer in Charlotte, N.C. He was a longtime columnist for The Charlotte Observer and a Pulitzer Prize finalist in commentary. Follow him on Twitter @tommytomlinson or email him at tomlinsonwrites@gmail.com.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "Precious Memories."