What It's Like to Draw Blood From a Whale Shark

In a remote bay in Indonesia, American researchers have partnered with local fishermen to uncover the mysteries of world’s biggest fish.

A speckled fin, three feet long, flicked out of the water as Al Dove surfaced in a morass of fish guts and foam. Behind him, a nightmarish cartilage slit of mouth gasped above the waterline, then lowered back into the spray.

As the sun sank over Cenderawasih Bay, the wind sent swells the color of spilled ink surging through a tangle of fishing nets, which Dove was sharing with a whale shark. It was a juvenile male, but still a powerful, seven-meter creature with skin like sandpaper.

Swimming with whale sharks as they circle in open water—bulked-out versions of the familiar, menacing shark silhouette—is a potent experience. Being in the net with them is an order of magnitude more intense. “You do feel a little insignificant,” Dove says. “That’s good. I think we all need to be reminded that we’re insignificant from time to time.”

Dove, a garrulous, heavyset Australian, is the vice president of research and conservation at the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta and one of the world’s leading whale-shark experts. Along with colleagues, he spent nine days at sea in July and August in this remote bay on the northern side of West Papua. The expedition crew hope that the data they gathered will help answer just a few of the many questions that remain about the world’s biggest fish, a vulnerable species that is still barely understood by science.

Because of their size, weight, and speed, and the difficulties of performing meaningful examinations on animals at sea, most of what is known about whale sharks comes from tests in aquariums or observations of their seasonal feedings around the world. The dozen or so experts on the species have to try to piece together an understanding of the animals’ life cycle from a patchwork of details that has glaring omissions.

“It starts with really basic demographics: How many are there? Where do they give birth? Where do they mate? Where are all the big males? Where are all the small females?” Dove says.

Which is where a two-man team from Conservation International that joined Dove—Mark Erdmann, vice-president of Asia-Pacific marine programs, and Abraham Siantar, the organization’s local shark and ray specialist—come in. Cenderawasih is unusual in that its whale shark population is not seasonal, but present all year round. It is also isolated: Getting there even from the Indonesian capital of Jakarta means a minimum of three hops on a plane and a long boat ride. That makes the bay, a wide expanse of sheltered water speckled with pristine reefs and home to dozens of unique species—several of which Erdmann, a veteran marine biologist, first described—a kind of laboratory for studying whale sharks.

At night, the bay glitters with the bright white lights from bagans, a traditional Sulawesi fishing platform made up of a central hull fitted with wooden outriggers and strung with nets and lines. The lights draw in baitfish, which in turn attract whale sharks. Sometimes, the sharks get caught in the nets. A few years ago, brainstorming ways to fit bulky, long-lasting satellite tags onto the sharks’ dorsal fins, Erdmann and Siantar settled on the bagans. “It struck us: This is a golden opportunity to have a whale shark in a constrained environment,” Siantar says.

Since 2015, Conservation International, a nonprofit based in Virginia, has fitted more than two-dozen fin-mounted tags on whale sharks in Cenderawasih. They uploaded videos of the work to YouTube, where Dove noticed a striking similarity between the way that the wild sharks sit in the bottom of the bagan nets and the way that the Georgia Aquarium’s four captive animals relax into the vinyl slings that the aquarium uses to perform veterinary exams.

The two organizations started to exchange emails, and after a year of planning, they chartered the Putiraja, a wood-framed, white-hulled cruiser out of Sorong, and sailed to Cenderawasih in late July. Once anchored in the bay, Siantar boarded a motor launch just after sunrise each morning to do the rounds of the bagans. Promised a bounty of 1 million rupiah ($75) per shark, local fishermen lured the animals into their nets with handfuls of baitfish, churning up the water with buckets as the sharks drifted in slow orbits around the platforms.

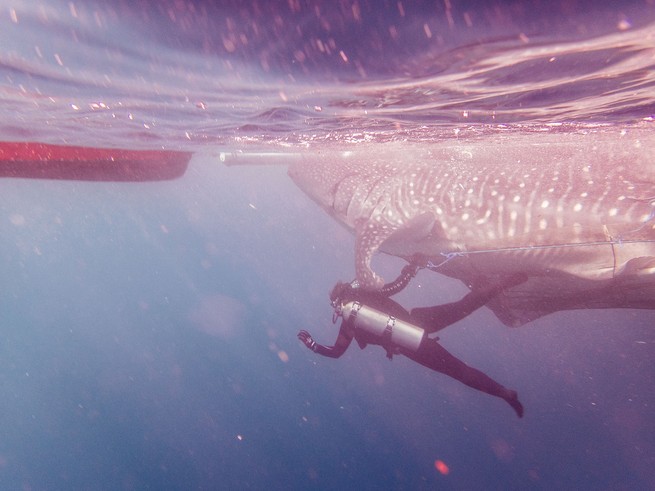

Once an animal crossed into the net, Dove, Erdmann, and Siantar joined it. While Erdmann took photos of the shark’s distinguishing features, Dove got a hold of it, stretched out along its flank in something halfway between a wrestling move and an embrace. Individual sharks reacted in different ways. Some sit still at the bottom of the net; others, like the juvenile male Dove swam with, struggled, thrashing their tails and writhing as the divers clung on.

Once he had a solid grip, Dove had to find a vein in the shark’s pectoral fin, a rigid slab covered in skin an inch thick, and insert an 18-gauge needle, the kind used by doctors to put a spinal tap into a human. It often took several goes—“It’s basically a blind stick” Dove said. Blood congeals quickly in the tropical heat, so as soon as the syringe filled up, Dove swam back up to hand it off to a colleague in a waiting speedboat, which powered across the bay to a makeshift lab set up on the stern of the Putiraja.

Sharks that have been previously tagged have been given names: Mitch, Mr. Caspar, Barack, Moby and, inevitably, Sharky McSharkface. Siantar and Erdmann took old tags off any they caught, so that they could download granular data on the sharks’ movements. Particularly interesting new animals had tags fitted. The pair used a pneumatic drill powered by air from a scuba tank to punch four holes in the dorsal fin and secured the device with steel screws.

Dove’s team took second blood samples on newly tagged sharks so that they could judge how stressful the process was to the animal—the answer being not noticeably. For all their majestic grace, whale sharks are “pretty much as dumb as dirt, and aren’t easily stressed out, anyway,” says Erdmann.

It was exhausting work, six hours in the water each day. The weather could shift in an hour from fierce equatorial sun beating down on sapphire seas to high swells and pin-sharp rain. On the penultimate day, two bull sharks, attracted by a thrashing whale shark, were spotted circling low below a bagan where the team were working, prompting a few tense moments.

In the end, the Putiraja sailed with samples from 20 individual whale sharks. They are still a long way from filling in the missing pieces in the whale shark’s life cycle, but Dove and his colleagues can at least use this data to build a benchmark for what healthy, wild whale shark blood should look like.

That will have practical uses for conservationists, who worry about the impacts of overfishing, pollution and tourism on the well-being of the sharks, which are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of vulnerable species. “It gives us something to work with when we start looking at places beyond Cenderawasih, where you're dealing with bigger problems with pollution, more tourism interactions,” Dove said. “Now we’ll have a good idea what the baseline is.”