An extensive ten-year study published in Schizophrenia Research explores the relationship between antipsychotic treatment and long-term outcomes in people diagnosed with psychosis. Among other findings, this Danish study finds improved functioning and higher rates of employment after ten years in those remitted off of antipsychotic drugs. In addition, the remission rate for patients off antipsychotic medication was higher than for those on the medications.

“Since antipsychotic medication can cause adverse effects e.g. extrapyramidal symptoms and a highly increased risk of metabolic syndrome, it is important to identify which patients might be able to obtain stable remission without continuous use of this medication. This subgroup is not fully taken into account in the present guidelines and further investigation on long-term perspectives is needed.”

Previous reports have called attention to the adverse long-term outcomes of antipsychotic use. The authors of this study further point out that while there have been numerous studies completed of long-term results that include remission of psychotic symptoms, few have assessed the correlation of long-term outcomes and antipsychotic medication.

They do, however, highlight one study from 2001 that found a large number of participants who had good outcomes at 15 and 25 years after onset regardless of their mediation status. Other studies that have also examined the relationship between medication and psychotic symptom include the AESOP-10 and Chicago studies. In the Chicago study at 4.5 years follow-up participants, not on antipsychotics, had significantly fewer psychotic symptoms those on antipsychotics.

This study aimed to investigate long-term outcome and characteristics of patients in remission of psychotic symptoms while not being on antipsychotic medication at 10-year follow-up. To do this, 496 patients between the ages of 18-45 years, diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders from the Danish OPUS-cohort were included. The OPUS trial was an RCT exploring the effects of intensive early-intervention.

At intake, patients had not received antipsychotic treatment for > 12 weeks. Measures included diagnostic tools (Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN); symptoms measures (Scale of Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Scale of Assessment Negative Symptoms (SANS); premorbid IQ (Danish Adult Reading Test (DART); functioning level (Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF-S, GAF-F); duration of untreated psychosis (DUP; Interview of Retrospective Assessment of Onset of Schizophrenia); and evaluation of antipsychotic medication use as well as compliance with the drug. Patients were divided into four groups: remitted off medication, remitted on medication, Non-remitted off medication, and Non remitted on medication.

Sixty-one percent of participants (303) participated at 10-year follow-up. After excluding deceased (n=33) and those that moved (n=18), follow-up rate was 68%. Those who took part in the 10-year follow-up had significantly higher functioning scores and were significantly younger than those who did not participate at 10-year follow-up.

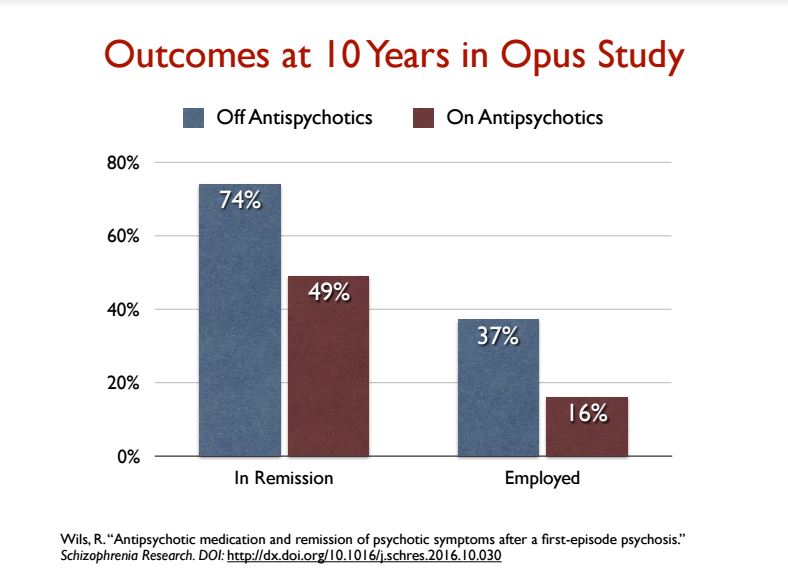

There were 121 patients off medication at the end of 10 years, and 182 who were taking antipsychotics. Seventy-four percent of patients off medication were in remission (90 of 121), compared to 49% in the on-medication group (90 out of 182). This produced an overall remission rate of nearly 60% for the 303 patients in the 10-year-followup.

“The high rate of patients achieving remission of psychotic symptoms regardless of medication status (around 60%) in our study is congruent with results from a large cohort study by Harrison et al. In their study about 50% of the patients achieved a good outcome 15 and 25 years after onset.”

In this study, a significant association between female gender and a more favorable outcome was reported. Higher functioning scores at the 10-year follow-up were associated with better long-term outcome. Moreover, there was a positive association between having a job/being in training/educational course/vocational rehabilitation and being remitted off medication. Related to this finding, better long-term outcomes were strongly associated with occupational status. Those that remitted off medication had the lowest scores of negative symptoms.

There was no relationship between age at inclusion, nor was there a correlation between better outcome and finishing high school or score on the DART (premorbid IQ). Lastly, a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was associated with poorer outcome.

Previous researchers have discussed the lack of evidence for the standard practice of long-term antipsychotic use and the potential adverse outcomes. The authors of this study provide some evidence on the effects (or lack of) of long-term antipsychotic use on psychotic symptoms. The authors of this study point out that while studies of discontinuation/dose reduction have found poor outcomes, these RCT’s had shorter follow-up periods (1-2 years vs. 10 years). This study adds to our complex understanding of the effectiveness of antipsychotics and their long-term impact in reducing psychotic symptoms.

An interesting although not surprising finding in the study was that participants in the remitted off medication group had significantly higher functioning scores, lower levels of negative symptoms, and more frequently participated in the labor market. This underscores the adverse long-term functioning outcomes that can result from taking antipsychotic drugs.

****

Wils, R. S., Gotfredsen, D. R., Hjorthøj, C., Austin, S. F., Albert, N., Secher, R. G., … & Nordentoft, M. (2016). Antipsychotic medication and remission of psychotic symptoms 10years after a first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. (Abstract)

Well… at the MIA article (the original is paid, 36 $USA), after 10 years the SZ not taking medications… have a full-entire-total-to-show… of 37% of them with a job.

And does not say what kind of job (low pay jobs? part time jobs? unqualified jobs?)

Yes they do betther than the lobotomized SZ folks. Those are nice people, fully passive, have acess, are satisfied with their way of life, dont shake the boat, and fully respect all laws.

Those SZ that take their pills/injections… are the number 16.

16 of 100.

Applause!

“I stand here waiting for

You to bang the gong

To crash the critic saying

Is it right or is it wrong?”

(music by Lady Gaga)

Report comment

As a schizophrenic, what do I want a job for? whats the point? F that sht

Report comment

Dead beat club song by B52 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5KyhesAa-DA

Report comment

A better link

“Once diagnosed, never undiagnosed. But once diagnosed, not always symptomatic.”

https://web.archive.org/web/20120626011756/http://www.furiousseasons.com/archives/2007/12/once_diagnosed_never_undiagnosed.html

“What’s the point of treatment and going through years of agony and finally getting vastly better only to be told that there is no goal line I can possibly cross that will lead to me being undiagnosed?”

Report comment

No kidding. Did you read the article on Marxism and mental health? (I haven’t experienced psychosis, but major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, etc.. and am on SSDI due to that shit combined with chronic physical illness) but feel the same way. Actually I question anyone’s sanity who doesn’t question the fact that the labor they have to do just to survive is what maintains and increases some other person’s billions. Ability to work shouldn’t be seen as a sign of health.

Report comment

“Remission” according to a Google definition search is “a diminution of the seriousness or intensity of disease or pain; a temporary recovery.”

Temporary? So they are expecting a return of intensity for these 74 % of patients off psych-drugs?

Despite the rhetoric, I’ve very leery of cancer “mental illness” comparisons, and I would imagine more research is in order.

It would be nice to see a few patients, on or off psych-drugs, fully recovered. Maybe they could use a few more 20 + year studies.

Report comment

My thought exactly…remission??

Uhmmmm, what about recovered?

The use of “remission” for full functioning after 10 years validates false arguments that “mental illness” is there for life and that there can be no permanent recovery. Friends of mine have been told they have gone into remission immediately after cancer treatment and are fully recovered after five years clear of cancer, and yet 10 years clear of “psychosis” is still considered “remission”?

So, how long does one have to be fully functioning, “medication”-free etc to be considered recovered?

…Or, perhaps more poignantly, why is a “psychotic” event considered an illness at all, rather than an event that can lead to personal understanding, growth, and development if treated sensitively, compassionately and wisely?

This and other studies have shown that “antipsychotics” lead to worse outcomes and/or permanent brain damage, and yet psychiatry continues to prescribe these drugs at ever increasing rates.

When will psychiatry remit and allow it’s victims to recover?

Report comment

They HAVE to say “remission,” no matter how complete the recovery. If they say “recovered,” the are admitting that their “permanent brain disease” meme is a bunch of crap.

Report comment

Since the antipsychotics can make people psychotic, via anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning, it’s not surprising that people do better off of these toxic torture drugs.

As to who should be taken off these drugs, since “the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).” And child abuse is a crime, not a brain disease, it would likely be a good idea to start weaning the child abuse victims off these drugs. Although no one should ever be forced or coerced into take this class of drugs.

Report comment

“Danish Study Finds Better 10-year Outcomes in Patients Off Antipsychotics”

Here’s a good title for an article:

“Polish study finds better overall outcomes for those who don’t leap from 200 foot precipices and land on jagged rocks”

Report comment

This made sense until this line towards the end: “Lastly, a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was associated with poorer outcome.”

So, outcomes are better 10 years post-diagnosis if you were first on drugs– for how long?– and then not? Rather than if you were never on drugs? So it’s beneficial to take them when you’re first diagnosed and in a very acute phase, but not longterm? Or is it better to never take them, and to have had non-drug treatment, but still treatment of some kind? Maybe such conclusions can’t be drawn from this study. I’ve read the book Mad In America and it’s quite convincing that being on any psychotropics for more than a short-term period does more harm than good. But I’m not sure if this study shows that being on them briefly is more beneficial longterm than never taking them. So I’m not quite sure what the takeaway is here, yet at the same time am always glad when drugs are exposed as being harmful longterm, and that they are far from being cures.

In the US there is virtually no non-drug treatment you can get without also being on drugs. Psychiatrists will tell you they won’t even see you if you refuse to take drugs.

Report comment

Is it possible to give a rough guess on the long-term effect of antipsychotics on recovery?

Antipsychotic medications are viewed as cornerstones for both the short-term and long-term treatment of schizophrenia. The evidence for symptom reduction will be critically reviewed. Are there benefits in terms of recovery?

Leucht et al has 2009 found (How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials) the effect NNT(Number Need to Treat)=6 for short time treatment (1). However this was looking at symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Leucht et al 2012 looks at maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs. Between 7 to 12 month are covered. The results published are better but conclude that it is necessary to “clarify the long-term morbidity”.

Bola et al. Cochrane.org 2011 (5) found just 5 studies with real placebo, i. e. RCT (Randomized controlled trial). One of them Rappaport et al 1978 found that umedicated patients managed better, e. g. readmission into hospital. NNH turned out to be 2.9 (NNH= number need to harm).

The Council of Evidence-based Psychiatry exists to communicate evidence of the potentially harmful effects of psychiatric drugs to the people (3).

Nancy Sohler et al. gives 2016 this summary: «For many years, this (…)clinicians’ belief in the need for long-term use of antipsychotic medications strong (Lehmann, 1966) that it has been impossible to design a sound observational study to address the question of efficacy or harm … (O)ur study also could not conclusively evaluate whether long-term antipsychotic medication treatment results in better outcomes on average. We believe the pervasive acceptance of this treatment modality has hindered rigorous scientific inquiry that is necessary to ensure evidence-based psychiatric care is being offered.»

So I understand there are nearly no RCT controlled studies (avoiding «cold turkey» problems) answering my question on recovery.

However is it possible to use other studies to evaluate effects based on other studies and real world results?

Approx. 60% or so of first-episode patients may recover without the use of antipsychotics.

Naturalistic studies of e. g. Harrow, M. & Jobe, T.H. (2012), Harrow et al 2014 (11), Wunderink (4,7) and Wils et al 2017 show that patients do better without long-time antipsychotic medication. Harrow, M. & Jobe, T.H. (2017) concludes in “A 20-Year multi-followup longitudinal study assessing whether antipsychotic medications contribute to work functioning in schizophrenia”:

“Negative evidence on the long-term efficacy of antipsychotics have emerged from our own longitudinal studies and the longitudinal studies of Wunderink, of Moilanen, Jääskeläinena and colleagues using data from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort Study, by data from the Danish OPUS trials the study of Lincoln and Jung in Germany, and the studies of Bland in Canada,” (Bland R. C. and Orn H. (1978): 14-year outcome in early schizophrenia; Acta. Psychiatrica Scandinavica 58,327-338) the authors write. “These longitudinal studies have not shown positive effects for patients with schizophrenia prescribed antipsychotic for prolonged periods. In addition to the results indicating the rarity of periods of complete recovery for patients with schizophrenia prescribed antipsychotics for prolonged intervals, our research has indicated a significantly higher rate of periods of recovery for patients with schizophrenia who have gone off antipsychotics for prolonged intervals.”

Jaakko Seikkula et al 2010 (Journal Psychosis Volume 3, 2011 – Issue 3) has reported on long-term outcome of first-episode psychotic patients treated with Open Dialogue Therapy in Western Lapland approx. 80% recovery (6). “Showing the benefit of using not much medication supported by psychosocial care.” The effect of cognitive therapy (8) and psychotherapy (9) is documented.

Bjornestad, Jone et al. 2017 reported “Antipsychotic treatment: experiences of fully recovered service users”: “(b)etween 8,1 and 20% of service users with FEP achieve clinical recovery (Jaaskelainen et al., 2013)” under the profession’s current protocols.

In order to maintain the narrative of antipsychotis beeing “effective” schizophrenia is falsely declared cronic i. e. drug dependence is preferred over recovery.

Now I know this guess is not exact science, but does it seem that approx. 40% of patients subject to regular medication (e. g. in Norway “National guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of individuals with psychotic disorders”) loose long-term recovery compared to non-medicated patients?

Would this be a fair guess of the long-term effect of antipsycotics on recovery?

Morrison et al. 2012 (8) concludes «A response rate analysis found that 35% and 50% of participants achieved at least a 50% reduction in PANSS total scores by end of (cognitive) therapy and follow-up respectively» i. e. NNT=2 for «follow-up» with cognitive therapy. Antipsychotic drugs perform NNT=6 according to Leucht et al. 2009. This shows Klingbergs conclusion (9): “In conclusion, psychosis psychotherapy does not have an evidence problem but an implementation problem.”

Patients have a right to know in advance to decide with informed consent the benefit of actual symptom reduction in the beginning at the price of long-term reduction of recovery. Where there is a risk there has to be a choice.

I would appreciate your answer based on your knowledge of studies. Thank you in advance.

Report comment