Is Hybrid Publishing Always the Best of Both Worlds?

I’m going to admit right from the start that this might be a controversial post. My goal is to explore issues while not “bashing” specific groups, but we’ll have to wait and see if I succeed.

We’ve often heard that having the cachet of a publisher name behind us will help no matter how we decide to publish further down the line. I know many authors who want to traditionally publish their first couple of books to build up a name for themselves and then transition to self-publishing for at least some of their later work.

The Hybrid Publishing Path

Bob Mayer coined the term “hybrid” for authors who publish both traditionally and on their own. This has often been described as the best of both worlds.

Hybrid authors get the benefit of a publisher brand, which might come with higher respect, more review opportunities, and wider distribution in print or tricky markets like libraries, etc. They also get the benefit of being able to control the release schedule, pricing, covers, etc. of their self-published works to maximize their income.

Several surveys have shown that hybrid authors have the highest earnings, compared to traditional-only and self-published-only authors. This isn’t surprising if the traditional releases are connecting with a broader spectrum of readers and the self-published releases are bringing in higher royalty percentages.

This best-of-both-worlds idea has inspired many authors to pursue the traditional publishing path even though they plan on self-publishing in the long term. So I’m always interested in more data about how this approach works for authors.

Does Having a Publisher Behind Us Always Help?

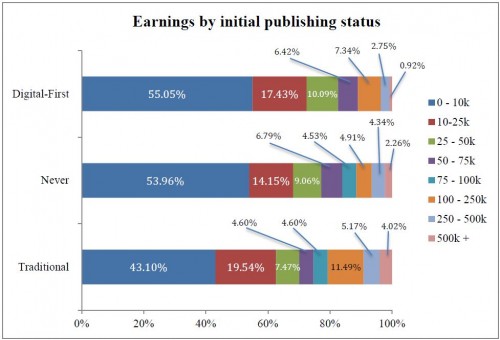

One of the observations Beverley Kendall made in her fantastic self-published authors survey struck me in regards to this issue. On page 4 of her report, she compared the earnings of hybrid authors coming from a traditional publisher, the earnings of hybrid authors coming from a digital-first publisher, and the earnings of self-published-only authors.

She found that being published with a digital-first publisher—on average—actually hurts hybrid authors’ income. While hybrid authors coming from New York-style traditional publishers did have the highest income, the self-published-only authors—with no publisher name to back them up—beat the digital-first hybrid authors income-wise.

- For traditionally published hybrid authors, 29.69% earned more than $50K.

- For self-published-only authors, 22.83% earned more than $50K.

- For digital-first hybrid authors, 17.43% earned more than $50K.

The only range that digital-first hybrid authors out-performed self-published-only authors was at $100-250K. Most of us would be thrilled with $100K, so some authors are definitely succeeding in their digital-first hybrid path, and this shouldn’t be taken as a slam on epublishing in total.

That said, Brenda Hiatt’s “Show Me the Money” page reveals low earnings on average for virtually all small publishers—digital-first/epublishers and traditional independent presses alike. Some of us have a goal of income and want to take this history into consideration, and some of us would rather have a partner helping us through the process and thus might discount these reports.

There’s no wrong answer. Only what’s right for us.

Why Doesn’t Digital-First Always Help?

Understanding the income situation might help us decide the best path for us, but I also wanted to explore the other variables affecting Beverley’s results. After all some of the other variables might affect whether a certain path will work for us despite the initial evidence.

Low Sales: Brenda’s “Show Me the Money” page implies that most small publishers can’t push big sales. Especially not enough sales to make up the difference to the cut in royalty compared to self-published-only authors.

If our royalty would be 20-35% less with a digital-first publisher than it would be by self-publishing, the publisher would need to generate that many more sales than we could get on our own to make up the difference. Some digital-first publishers could manage this and some couldn’t. Some of us might have a strong platform on our own and some might not. So there’s no set answer for every author and every situation.

Resistance to Free: Beverley also saw in her survey results that fewer digital-first hybrid authors offer a free series-related book. As we discussed in my initial posts about Beverley’s survey (here and here, and consolidated into my guest post at Kristen Lamb’s blog yesterday), offering a free story to attract readers is part of a successful strategy.

We find this as a differentiating factor between digital-first hybrid authors and self-published-only authors, but traditionally published hybrid authors are even more reluctant to make a story free (page 24 of Beverley’s report). So while this resistance might be a contributing factor to digital-first’s poor showing for hybrid authors, it’s not the driving issue.

Quality: And here’s where this post might get really controversial. Many non-New York traditional publishers suffer from a bad reputation for quality. I’ll share more about this issue and the repercussions in Thursday’s post, but suffice it to say that “small press bad reputation” goes double (at least) for digital-first publishers.

So, many of the benefits for a hybrid author starting off with a publisher—the “higher respect, more review opportunities, and wider distribution in print or tricky markets” I mentioned—might not exist if said publisher is a digital-first publisher. Hmm…

Does This Mean We Should Avoid Digital-First Publishers?

As I stated above, none of this is meant to say that we should always avoid digital-first publishers. We all have different goals, and we might prioritize having a team at our back over some of these potential issues. Maybe our digital-first publisher offers a great contract (which is more unusual than it should be, unfortunately). Maybe our platform is next-to-nothing and any help would be better than none. Or maybe we’ve found a digital-first publisher who does have a good reputation.

We just need to be aware that all publishers are not created equal, especially so when it comes to the benefits for hybrid authors. As always, we need to find the path that works for us and not just imitate what we’ve seen others do. Our circumstances will be different from their circumstances and our goals will be different from their goals, so the only path we should take is the one that’s right for us. *smile*

P.S. Kristen Lamb announced a new WANACon giveaway on her blog yesterday. If you’re signed up for WANACon and you refer someone else to sign up, you’ll get 25 entries in a drawing for three branding and/or plotting consultations. These are incredible prizes and I hope some of my readers are among the winners. *grin* Just make sure your friend references your name when they register for WANACon.

P.P.S. I’m not eligible for this contest, so feel free to mention that you heard about WANACon and the giveaway from my blog, but give credit to another attendee. New signups who give credit to another attendee get 15 entries too. Yay!

Had you heard the advice to start with a publisher before branching into self-publishing? Are you surprised by the big difference the type of publisher can make for hybrid authors? Do you have other thoughts or insights into what might cause that difference? What’s your impression of the quality for digital-first publishers? Are you going to WANACon and want people to reference your name when they sign up? (If so, leave your name in the comments—and yes, moderators are eligible!)

Pin It

With the digital only books and small press books I’ve read – I’ve had no problem with quality.

I also see the reason for going digital only as a step in the traditional publishing ladder. Authors can use it to put on their resume, snag an agent (which happens a lot after they’ve already been offered the contract), and hope to move up in the world with their next book.

Of course, just like any publishing, it could possibly hurt them if sales are lacking. Digital only seems to accept manuscripts that print publishers might turn away. For the author who does not want to self publish, this is definitely an option. Many authors do not put the concerns about money first. And they want the editing and the partnership that comes with pairing with a publishing, even if it is digital only.

Books do how they’re going to do, usually regardless of how they are published or how much money and time is put into marketing. 🙂

Hi Laura,

Hmm, I wonder if there are different quality levels for digital publishers of different genres? That wouldn’t be surprising, and if trendier genres attracted more companies than good business people and editors to support them, I could easily see some genres being overwhelmed by poor quality digital-first publishers. But that would mean other genres could be relatively “safe” from poor quality too. 🙂

That’s a great insight–thanks!–and yet another reason for why I would never say that authors should avoid digital-first publishers out of hand. 🙂 And I agree completely that some authors have different goals and different priorities that would make digital-first a great choice. That’s why we all have to decide our own path. 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

My first book was published by a digital-only publisher. (They’ve since started offering PODs, and once they get their backlist caught up their ebooks and PODS will be offered simultaneously.) This imprint was part of a large, respected publishing company, so I felt very lucky to get in on the “ground floor” with them. I was lucky; I had a great editor who knew what she was doing. The changes she suggested were minimal, but her suggestions made my story tighter and better, and I ended up with a beautiful book. It turned out, though, that I was definitely in the minority. Since the imprint was in its first year, they were using a lot of free-lance editors, and the results weren’t pretty. There were more instances than I can count of unedited manuscripts being published with no one knowing what happened to the edits. Some books were even published with the editor’s mark-ups and notes in the book! It got so bad that Dear Author even announced publicly that they would no longer accept books from this publisher because the editing and overall quality was so bad. So there I (and a few other authors) sat, with a beautifully edited book that was being lumped in with the poor quality offerings from the publisher. My sales, as you can imagine, were less than stellar. Dismal doesn’t even begin to describe it. I’m happy to say that my publisher has done a complete 180 in the past year. Books are… — Read More »

Hi Juli,

Thanks for sharing your experience! That’s a great point about how many of the smaller publishers use freelance editors–and my Thursday post will look closer at this editing issue.

Oh no! That’s horrible! I’m so sorry you were caught up in that. 🙁 The smaller release numbers can definitely add their own risks for small publishers. As you mentioned, a handful of bad experiences can spoil the reputation of a small company far easier than for a big company.

That’s great advice! Every company will go through growing pains, some worse than others. So if we sign with an untested publisher, we should be aware of the risks. 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

Hi Juli,

As a freelancer who edits for a few small presses, I know how erratic it can be, but that isn’t always the editor’s fault. Sometimes the editor misunderstands what you were trying to do. And sometimes (…often, in my experience) the editor isn’t told what, precisely, they’re editing. If the editor doesn’t know if they’re working on a story for the MG, YA, or adult audience…that’ll change the way they see the story.

I had some hilariously wrong changes advised for one story of mine—but the content editor had thought it was supposed to be romance. I’d been accepted as part of testing the waters for a new genre, and my story’s genre had been lost in the grapevine. Once I pointed out the disconnect, the editor went Oh! and everything panned out well. The other niggles she pointed out were details I’d noticed myself but had forgotten to or decided not to address before sending.

Hi Carradee,

Wow! at your experience. I’m reminded of many small companies who don’t have good processes because they hand-walk things through their tiny bureaucracy where everyone knows everything. Then when they grow and people have to specialize, they fall apart because too many things get lost between here and there. (Yes, I have experience with process management, can you tell? 🙂 )

I could see that situation applying to small publishers and them struggling to ensure that freelance people (i.e. those outside of the everyone knows everything loop) get all the right information. We joke about things being lost in big bureaucracies all the time, but we don’t think how it doesn’t take much for it to happen at small places too. 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

My dream is to someday run my own pro-paying speculative fiction magazine or periodic anthology, like IGMS by Orson Scott Card or Fiction River by DWS and KKR. That’s one of the reasons I intentionally seek to work with multiple small presses. I’m observing how they handle things at various stages of their development, so if I ever do get to run that periodical, I’ll have some idea of what growth pangs I’ll need to watch/plan for. I also have to keep my natural inclination to boredom in mind. I’ve mentioned before that I’m a freelance writer, editor, and web coder—which is a broad enough skillset that even those times I’ve wanted to try the day job thing, I’m overqualified for most things and underqualified for specific things I’m close to. But the reason for that wide a focus (which frequently adds more skills in that umbrella—I finally learned how to make GIFs, recently), is that I need variability. If I spend too long doing one thing, I get irritable. I therefore intentionally seek varied work, to avoid that. Which means, if I ever do start that periodical, it’ll likely be best done under a small press handled by someone else. I’ll also have to make sure the project stays small enough that it stays a side thing I can enjoy, rather than becomes something that makes me want to chew my arm off to get away from. Ironic thing about that is, I’m not ADD. My mother and brother… — Read More »

Hi Carradee,

LOL! No worries. That sounds like a great goal for you! Good luck!

This is very interesting about digital first and I think you have some great points. I wonder how authors do in the digital first arms of the traditional publishers like Avon? A lot of the traditional publishers are going with a digital first line before they commit to the full print run for a new author. I assume you are not including them in the “digital first” category? Or are those models too soon to rate?

Hi Heidi,

My Thursday post will touch on that. 😉

I will say that every publisher should be judged on their own merit. While that means that we shouldn’t lump all digital-first publishers together, that also means that we shouldn’t assume a digital-first imprint is good quality simply because it’s associated with a large traditional print publisher.

Many of the digital-first imprints of trad publishers are the one who gave digital-first publishers the reputation for poor contracts. (Not that the other epublishers didn’t suffer from this issue, but their contracts didn’t garner the headlines.) And as you said, in some ways, epublishing is so new that the dust hasn’t settled yet to leave the good companies behind.

There’s nothing inherent in the digital-first business model that requires bad quality, so I think a few years from now–after that dust settles–we’ll be able to see the quality publishers more easily. 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

I appreciate your thoughts. There’s a lot to make sense of in publishing. It’s so important as authors, agented or not, to make decisions where we are in control of our career.

Hi Stephanie,

As I mentioned on Facebook, I want people to be aware of the potential issues–of ALL paths. Honestly, I’ve picked apart the difficulties and issues of self-publishing and Big 5 plenty of times, so this post certainly shouldn’t be taken as advocating one path over another.

I know some authors who have found success on the digital-first path, but I also know many authors who have taken this path and were burned by it. So I felt it would be a disservice to not explore the issues. 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

I’m a hybrid author who was first published by a small digital press (they also have POD, but that’s digital technology as well.) I’m doing okay, but certainly not as well as my friend who started out with Simon and Schuster.

But there’s such a wide range of small presses, and at this time of upheaval in the business, some are still stuck in the old paradigm, and some are jumping on a bandwagon they don’t know much about. So I think the important take-away from this study is: vet your small or digital-only press carefully.

Also, it’s important to know the time period when the data was collected. Carina and Avon’s digital wing started out with kind of rotten royalties as I remember. They may be better now. Some of this data may have come from that time.

Hi Anne,

Exactly! There’s a huge range of quality among small presses. That’s to be expected from any collection of relatively new businesses, to be honest. 🙂

Good point too about paying attention to how old any feedback is, either from surveys or from Absolute Write forums, etc. The business is changing so fast that data quickly falls out of date. Thanks for the comment!

Hi, Anne.

It’s funny that you mention Carina. I’ve seen a few sources mention that their royalties have, in fact, gone up—and that increase has evidently been applied across the board. But that info isn’t exactly easy to find. As for if the data came from when the royalties were lower, I daresay that’s impossible to say. At least part of it probably is, which may skew the numbers, but maybe not.

Hi Carradee and Anne,

I know Beverley’s survey specifically asked about 2013 earnings, but yes, this is an issue to keep an eye open for with surveys in general. 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

My small press experience so far has actually been with experiments run by the small press in question, with them trying styles/genres other than their norm. The first experience was, um, unpleasant, as you may vaguely remember. My more recent experience has been pleasant, but sales have been low enough that I’m surprised they offered me a contract for the sequel. (But then, in that case, the company owner and I discussed things in advance and entered this knowing it may take the entire trilogy being out for it to gain any traction.) Then there are my primary two self-published series, which any publisher worth their salt would’ve told me to change. I considered making those changes that would make them more palatable to a general audience, but that would’ve changed the entire point of each story and series, so I decided to leave them as-is. I never expect them to take off dramatically, but I hope that once the series has a few more titles out, it’ll at least make a decent showing. It’s certainly doing great on Wattpad. So actually, nothing of mine is selling well. That said, I do currently have a story for which I’m seeking a contract, probably with a digital-first/only small press, because the story seems well-suited to that environment. I have a few possibilities in mind. If none of the (reputable) options pan out (or I don’t end up with a contract I’m willing to accept), I’ll self-publish that, but as things stand,… — Read More »

Hi Carradee,

Oh yes, I’ve submitted work to small and epublishers as well, so I obviously don’t avoid them all either. LOL!

The important thing about your situation now is that you’re in with eyes wide open and a set of personal guidelines about what contract details you would/wouldn’t accept. The possibility of making mistakes still exists–even with our knowledge–but we can try to minimize those chances. 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

Actually, that mistakes thing is one reason I’m a huge fan of contracts of a specifically limited duration. Even if the experience is horrific, if the duration’s reasonable, there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

Hi Carradee,

Agreed! Honestly, with as much as most publishers don’t do to push their backlist titles, I think almost every contract should have a time limit. 🙂

Actually, this is one area that many epublishers are ahead of traditional publishers. I’ve seen several epub contract with an end date, while that idea is extremely rare on the traditional/print end. 🙂 Thanks for the great point!

Like you said, everyone has their reasons for going down the path they chose. I chose a digital first publisher because I was working ten plus hours a day and had a young family. I was sure that I wouldn’t be able to doe everything that needs to be done to successfully self pub a book and still actually sleep at night.

The second reason, and I will put this out there now, is fear. Going it alone can be scary.

I’m slowly talking myself into taking the leap to self pubbing, but so far, it’s been the small press for me.

Thanks for the post.

Hi Lynn,

I completely understand both of those reasons and support your choices. 🙂 We often tell ourselves that we’ll do X (start writing, exercise, publish, etc.) next month when it calms down and we have more time. But too often, our lives never calm down and instead of making progress, we’re stuck in a loop of waiting for the perfect time that won’t ever happen.

So it makes complete sense for you to head off that loop and take the step you knew you could take. 🙂 Congratulations on succeeding where so many of us get caught! LOL! Thanks for the comment!

[…] I mentioned in my post last week, I don’t mean to pick on digital-first epublishers. However, many epublishers (and smaller/newer publishers) have a bad reputation for editing […]

Excellent topic, Jami! I’m fascinated by these numbers. Hugh Howey’s free WOOL (book 1) is the main reason why I became a rabid fan of his series. His genre is not what I normally read. I gave it a try because I had nothing to lose. It’s something I’ll remember with future releases.

I’ve had quality issues with trad. pub’d books from major houses. Just the other day I set aside a book by a major author from a major house. You just never know in this business!

But you’re right…each author should do what works best for them. And research the heck out of every avenue.

Hi Julie,

Great point! Freebies can lure in readers simply because they have nothing to lose. 🙂

Like you, there are now publishers I stay away from because of quality issues. There’s never a simple answer, is there? 🙂 Thanks for the comment!

[…] of the project and the rights they happen to hold. While there is some limited evidence that these hybrid authors do better on average than those who exclusively pursue one or the other means. Still, it requires writers to […]