The Rise of Curiosity Journalism

On the web, curiosity rules—but all curiosities eventually become routine

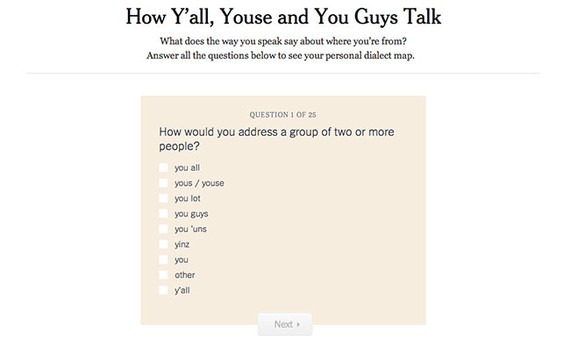

Last week on these very pages, Robinson Meyer noted the surprising fact that the overall highest-trafficked story at the New York Times in 2013 was not a story at all, but a news interactive about American dialect, “How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk.” Rob further noted the startling fact that the app achieved this feat in the final two weeks of the calendar year.

I’ll repeat: It took a news app only 11 days to “beat” every other story the Times published in 2013. It’s staggering.

It’s certainly startling. But is it really surprising? Perhaps not, once we consider the dominant patterns of online attention, and how those patterns intersect with the Gray Lady’s overall editorial direction.

For one part, the present-day web has evolved to direct the largest swaths of traffic from a few social media sites. As Alexis Madrigal noted in his own post on the top stories of 2013 here on The Atlantic Tech, “these days, making the top 10 list nearly requires hitting on Facebook or Reddit.” Indeed, our own top-trafficked stories are also curiosities: This Guy's Car Got Stuck at 125mph—for an Hour and the GIF of popular baby names since 1960.

So, it’s not really a surprise in itself that a curiosity like the NYT’s dialect quiz might hit big online. What is surprising, however, is the very fact that this curiosity is a curiosity.

If you look at the entire list of top-ten New York Times stories, you’ll see what I mean. Three of the top ten stories, including spots two and three, were coverage of the Boston marathon bombing. The fourth and fifth were guest editorials by famous people (Angelina Jolie and Vladimir Putin). The tenth covered the selection of Pope Francis, and the remainder offer traditional coverage of issues in health and politics.

It turns out that “How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk” wasn’t just a curiosity for the Internet, it was also a curiosity for the New York Times itself. The feature is actually rather plain-vanilla, a quiz with dialectual heat maps that locates the reader’s speech within a particular region. It boasts a staid and unassuming design, and it presents its results without the fanfare and flourish common to online media desperate to go viral. But in the context of the New York Times, even a modest app like this is an outlier. In other words, the very fact that the curiosity that is “How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk” is a curiosity for the NYT makes it an even greater curiosity, and thus one even more susceptible to sharing and linking. It also makes the feature’s relative popularity subject to a different traffic scale. Because the Times publishes so few curiosities, it’s much easier for a piece on its virtual pages to become a curiosity.

What about the fact that the dialect quiz and maps still managed to make it to #1 within the last week of the year? The unexpected, precious nature of a NYT news app might partly explain its sudden popularity, but the quiz’s timing must have played another part in its success. On the one hand, the week of Christmas and New Year’s seems like a terrible time to publish anything; readers are often traveling or visiting with family. But on the other hand, this downtime also offers a great opportunity to play with distractions like a dialect quiz. Such a quiz is likewise compatible with family gatherings: multiple people in the same place with different backgrounds and from different places—all with their smartphones and tablets at the ready. The NYT venue also might make it more amenable to spikes in usage and sharing than other, less familiar sites. Put more simply, an interactive app on the New York Times offers the best of both worlds: the weird pique of web virals along with the safety and reputation of the Gray Lady.

“How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk” is a double-curiosity, both a weird sharable that scratches the Internet’s favorite itch, and a weird outlier for a traditional publication like the New York Times. This scenario also puts the #1 spot in perspective. For a traditional publication that publishes relatively few curiosities, traffic spikes are themselves unusual, and being #1 at the Times means something different than being #1 at Buzzfeed or Gawker (or even The Atlantic). Indeed, that’s the reason Rob was able to write a post about the top ten list (it was quite well-trafficked!), and why I’m able to write this response in turn. The form of online media is increasingly its subject.

In fact, the piece is rapidly becoming the curiosity that keeps on giving. In the wake of the revelation that Josh Katz, a North Carolina State University statistics student, had been instrumental in creating the quiz in question, Northwestern University’s Knight Lab wrote about “How an intern created The New York Times’ most popular piece of content in 2013.” Katz’s Twitter bio currently reads “statistician. data journalist. that guy who made those dialect maps.”

Katz and his kindred might just as well call themselves “curiosity journalists.” Curiosities draw the most attention when the story about the story exceeds the story itself. In this case, the question of why American dialects even matter as a topic of public knowledge and citizen debate has been abandoned, for better or worse, in favor of the idea of its existence. That is to say, popularity online now depends on a thing’s thingness, on its ability to distinguish itself as a unique and precious snowflake, rather than by its meaning or its function.

The very fact that a news quiz leads annual traffic in a newspaper of record cuts both ways. On the one hand, it suggests that newsmakers might want (or even need) to invest in more news apps and other uniquely digital features. But on the other hand, it underscores the fact that such features tend not to operate on the same journalistic register as traditional stories. A dialect quiz is fun and interesting, but do we really want it to be the most widely seen news “story” of the year? Even the New York Times isn’t sure. The Northwestern Knight Lab piece on the feature reveals that the newspaper almost didn’t publish it at all, and concludes that the feature is entertainment above all else. To quote Katz: ”at the end of the day it’s fun.”

Eventually, if news apps become more common thus more ordinary, they will no longer pique the public’s interest via their form and context. Fundamentally, curiosities might be opposed to journalism, even as journalists must now rely on them. And in the final analysis, every curiosity is temporary anyway. It’s not too hard to imagine a future in which the next generation of writers codes up an interactive editorial commenting on the surprising realization that the next type of curiosity out-performed all the other apps and listicles and tumblrs and animated GIFs and other fresh forms that will soon become tamed and uninteresting. Meanwhile, people will still hurt and cure one another, tugs-of-war over power and wealth will proceed indignantly, natural disasters will threaten, ruin, and relieve us, with or without our words, or apps, or robots.