Lucrecia Sjoerdsma knew what to watch for: the lingering moodiness, the sudden disinterest in what once brought joy. But her daughter, Riley Winters, a ninth-grader at Discovery Canyon Campus High School in Colorado Springs, Colorado, was always smiling—the 15-year-old used whitening strips because she loved showing off her perfect teeth. "Her smile really matched her personality," Sjoerdsma says. A petite girl with brown hair that went just past her shoulders, Riley seemed to be a happy, goofy kid and a kind young woman who could sense when others were down and find a way to cheer them up. Riley liked hiking and rock climbing. She spoke of joining the military or becoming an archaeologist, a physical therapist or a dental hygienist. She had plenty of time to decide.

Even though her mother had no sense that Riley was having problems, she knew it was important to talk to her daughter about suicide, and so she did. Between 2013 and 2015, 29 kids in their county had killed themselves, many from just a handful of schools, including Riley's. There had been gunshot deaths, hangings and drug overdoses. And then there were those choking deaths the victims' parents insisted were accidental.

Riley knew of at least two of the kids who had killed themselves the previous winter: an older girl at school (they had mutual friends) and a boy in her Christian youth group. Such peripheral connections are all that seem to connect most of the kids in the area who had killed themselves, and school and county officials began to worry they were witnessing a copycat effect...until copycat became too weak a word. It was more like an outbreak, a plague spreading through school hallways.

About a year after Sjoerdsma and her daughter last spoke about suicide, Riley was staying at her father's house one night when she downed a small bottle of whiskey, then sent out a series of troubling texts and Snapchat messages. "I'm sorry it had to be me," she wrote to one friend. Then she slipped on a blue Patagonia fleece and snuck out the basement window, carrying her father's gun.

When Riley's mother and friends saw the messages, they went looking for her at local parks, gas stations and friends' houses, all the while begging her via texts and calls to come home.

The next morning, they found her body in the woods behind her father's house. She'd shot herself in the head.

Three days later, and two days before Riley's memorial service, another Discovery Canyon Campus student killed himself. Her daughter probably knew the boy, but they weren't close, Riley's mother says. Nine days later, yet another classmate committed suicide. He had been on the swim team with the boy who'd just killed himself. And that wasn't the end of it: Five students from the school of 1,180 died by suicide between late 2015 and summer 2016, a rate almost 49 times the yearly national average for kids their age.

It's not just at that one school. As of mid-October, the total for teen suicides this year in El Paso County, home to Colorado Springs, is 13, one short of the total for all of 2015. Neighboring Douglas County had a similar crisis a few years ago, and news of a classmate's suicide no longer fazes students in the area, kids say. "It's become almost commonplace," says Gracie Packard, a high school junior in Riley's district. "Because it doesn't happen once every four years. It happens four times in a month, sometimes."

The youngest person to die this year in El Paso County was 13. "[Even] for a job that's generally pretty tragic, it's disheartening," says Dr. Leon Kelly, the county's deputy chief medical examiner. "You feel powerless. You feel like, Another one?

"Another day, another kid. It's hard."

Death on Instagram

Sociologists have long said people who form bonds are less likely to kill themselves, but sometimes the opposite is true—studies now show that one person's suicidal behavior can spur another's, and one death can lead to more deaths.

Decades of research prove that a startling range of emotions and behaviors can be contagious—from moodiness to yawning. Young people are especially susceptible; they obsess over fads and fashion trends and copy illicit behaviors from peers, such as smoking, drinking or speeding. Or suicide. Using a statistical formula typically applied to tracking outbreaks of diseases, researchers at Columbia University and other institutions confirmed in 1990 that suicide is contagious and can be transmitted between people. Contagion spreads either directly, by knowing a suicide victim, or indirectly, by learning of a suicide through word-of-mouth or the media. Those same researchers found that people ages 15 to 19 are two to four times more prone to suicide contagion than people in other age groups. The way it spreads can be so similar to that of diseases that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has sometimes gone into a region to investigate spikes in suicides.

Analysts call those spikes suicide clusters—an unusually high number of people in an area kill themselves (or attempt to) in a short period of time. The clusters tend to happen where people socialize, such as schools, psychiatric hospitals or military units. Madelyn Gould, one of the analysts who made the contagion discovery, has said these clusters make up between 1 and 5 percent of teen suicides but are vitally important to understand because "they represent a class of suicides that may be particularly preventable." And a few consecutive suicides can devastate a community.

Another reason it is crucial to understand these clusters is that suicide is likely becoming more contagious, thanks in large part to social media. Analysts have long assumed that a suicide typically has a profound impact on six people, but that estimate is from the early 1970s and limited to close family members. Social networks (both online and in real life) are much bigger today, and soon-to-be-published research by Julie Cerel, president-elect of the American Association of Suicidology, shows that a suicide may now touch around 135 people, and about one-third of them experience a severe life disruption because of that suicide. She and her colleagues previously found, in 2015, that people who know a suicide victim are almost twice as likely to develop suicidal thoughts as the general population. The closer the relationship, the greater the risk; the younger the person exposed, the greater the risk.

Young people aren't the only ones facing a suicide problem; the national suicide rate across all demographics is at an almost 30-year high. But more than three times as many teens are killing themselves now than in the 1950s. Most of these suicides aren't copycats, but some areas across the country are suffering from the sort of contagion that has stricken Colorado Springs; the CDC investigated cases in Fairfax County, Virginia, in 2014 and Palo Alto, California, in 2016. Other clusters have likely gone undetected because it's often so difficult to make the connections between victims.

Suicide prevention advocates tend to blame television and newspaper coverage for inspiring copycats, but for teens, social media are a growing problem. Instagram pages for kids who kill themselves sometimes contain hundreds of comments. Many are about how beautiful or handsome the deceased were, how they can finally rest in peace and how there should be a party for them in heaven. Dr. Christine Moutier, chief medical officer at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, says the message seems to be that if you kill yourself, you'll not only end your suffering but also become the most popular kid in school. Teens sometimes have more than 1,000 Instagram followers, so kids far beyond one school or community can see digital shrines to dead friends. Moutier says those posts can seem as if they're romanticizing death.

Scholars are struggling to keep up with the evolving technology, and they say there's still a paucity of research on how suicidal thoughts spread through social media. "It makes these deaths no longer isolated," says Cerel, and kids "are exposed and perhaps profoundly affected by someone they might have never even met in person." Analysts say clusters could become harder to spot, because they typically occur in a specific area, but social networks for teens now spread far beyond a school, a neighborhood, even a city.

The Choking Game

It's hard to identify "patient zero" in the Colorado Springs suicide outbreak because kids today are so interconnected, and the families involved have kept many details private. Researchers also know that they can't limit their search to one group; the first suicide at one school may have been inspired by the death of a student at another. Other factors muddling the search: The coroner's office doesn't always track where the deceased went to school, and districts are hesitant to say how many teens they've lost to suicide, citing student privacy laws and fear of copycats.

One known precursor to the current wave of suicides was in 2011, when a Colorado Springs father found his 12-year-old son suspended from a bunk bed. The parents insist it was not a suicide and instead blame the "choking game," in which a person cuts off blood flow to the brain and then releases it in order to feel lightheaded or even high. The coroner's office ruled the cause of death "undetermined." In 2013, a 15-year-old from the same school district strangled himself, and his parents blamed the choking game. The number of teen suicides started picking up in the spring of 2015, when a Discovery Canyon Campus student shot herself. The next month, three local kids took their own lives. From June to November, there were five more suicides in the Colorado Springs area; in December, there was on average one teen suicide per week. The deaths surged again toward the end of the last school year, beginning with Riley's suicide.

Those tracking the situation are convinced it's a contagion, but they're unsure how it's spreading. That makes it all the more frightening and difficult to stop. "It's two years in a row we've dealt with the same sort of terrifying trend," says Kelly, the medical examiner.

Colorado's Child Fatality Prevention System, which investigated all youth suicides in the state from 2010 to 2014, identified risk factors, including family arguments, relationship breakups and physical or emotional abuse. Others blame regional factors, like the nearby Army and Air Force bases, as the children of people serving in the military are at elevated risk for suicidal thoughts. (A parent's deployment can lead to increased responsibilities at home for a kid or emotional problems because of the separation and possibility of a parent's death.) Some blame the high altitude, which researchers have linked to suicide.

Analysts also point out that young people don't always know how to get through stressful times. Adults tend to end their lives because of major life stressors, Kelly says, but for a kid, the breaking point is often less significant. "These risk factors line up like lights on the street," says Richard Lieberman, a mental health consultant for the Los Angeles County Office of Education. "For a kid to go from thinking about suicide to attempting suicide, all these lights have to turn green." One light might be a fight with a parent. Another might be a flunked test, a breakup, a peer's suicide. Kids might contemplate suicide for months, and then the final act is often on impulse, "if everything falls into place," says Scott Poland, a school crisis expert from Nova Southeastern University in Florida. Poland and Lieberman are working with Discovery Canyon Campus and its district.

Riley didn't show any obvious signs of mental health problems, according to her mother, and wasn't in therapy or on medication. "Teachers even said, If you would have given me 200 names, hers would have been at the bottom of kids who would do this."

But Riley was having trouble in the classroom—she fooled around during class, and her grades suffered, which added pressure. "She kept saying she hated school; she just didn't want to be there," Sjoerdsma says. She also struggled with her parents' 2005 divorce. But even a few hours before her death, at a Christian youth group gathering she was dancing around and holding hands with friends, says Sjoerdsma, acting like "her normal self." In the car with family friends on the way to her father's house, Riley rolled down the window and stuck her hands outside. She liked to feel the cool mountain air on her palms. When she was dropped off, she told the people she was with that she'd see them tomorrow.

'Unhang' Yourself

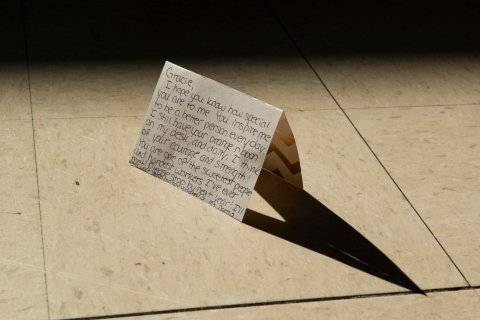

A little more than a week after Riley's suicide, Brittni Darras, an English teacher at a different school in the area, posted on Facebook that she had learned of another student's attempted suicide during a parent-teacher conference. "As her mom sat across from me, we both had tears streaming down our faces," Darras wrote. "Feeling helpless, I asked if I could write my student a letter to be delivered to her at the hospital." The mother agreed. After the student received it, the mother emailed Darras to share what the girl had said: "How could somebody say such nice things about me? I didn't think anybody would miss me if I was gone."

Darras had lost a student to suicide a few years earlier. "It's something that, as a teacher, you never entirely recover from," she says. "Losing one in my teaching career was more than anybody should ever have to go through." When she heard how the girl in the hospital had reacted, Darras decided to write letters to the rest of her 130 students. It took her two months. Her students were thankful, and word of what she did spread; nearly 200,000 people have shared her Facebook post.

Darras is one of many people in the Colorado Springs area fighting to stop the suicides. The initiative Safe2Tell, which began as a pilot program in the city in the 1990s and expanded statewide after the Columbine High School killings in 1999, lets young people anonymously report threats by others. State police receive the reports and connect with local law enforcement and schools to intervene. Last school year, Safe2Tell received 5,821 tips, up 68 percent from the previous year. The largest category involved suicide threats. "For years, in all the work in suicide prevention, we've really focused on one thing, and that is seeking help if you need it," says Susan Payne, the initiative's executive director. "That meant putting it on the victim that's struggling to make a phone call or seek help." Her program encourages bystanders to look for warning signs in others and report them.

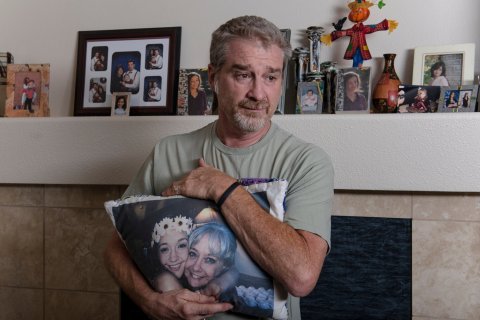

Daniel Brewster wants that too. On December 31, 2015, hours before he and his daughter Danielle, 17, a Discovery Canyon Campus student, planned to celebrate the new year, she hanged herself. Brewster later looked at his daughter's phone. "This is the part that kills me—I know she was texting other kids at the time and letting them know," he says. She wrote, "My feet are off the floor," and "Everything is getting hazy and dark." None of the kids intervened; one responded by suggesting she "unhang."

"Just having a meeting with [teens] and saying, 'OK, here are the signs; here's what you look for; here's what you need to do'—that's not enough," Brewster says. "It needs to be ingrained in these kids' heads, because they're our first line of defense." Of all the young people in Colorado who killed themselves from 2008 to 2012, more than a third had told someone of their plans, according to a state report.

Danielle's was one of at least three teen suicides in the Colorado Springs area in a three-week span. Then, six weeks later, Danielle's mother hanged herself in her daughter's bedroom. "They're supposed to be here," Brewster says, choking on the words. "We're supposed to be in this house together."

Some local students are starting their own prevention efforts. Gracie Packard was in the eighth grade when she set a date to kill herself. She had struggled with anxiety and depression since she was young and later practiced cutting. She couldn't sleep, her grades were slipping, and she was losing weight. She would cancel plans with friends and stopped dancing, once a passion of hers. Meanwhile, other kids around town, as well as one of her siblings, were killing themselves or attempting to. "It was pretty much all around you," she says. She recalls telling herself, "If things aren't better by this date, then you've tried your best, and you can end it."

Her friends sensed something was wrong. Days before she planned to die, they staged an intervention. "We're worried about you," they told her. Their concern, plus a suicide prevention nonprofit she stumbled upon called To Write Love on Her Arms, convinced her to ask her mom for help. "I was physically shaking. I could hardly breathe," she says. But "that 30 seconds of bravery in being willing to say out loud to somebody you trust that, 'Hey, I'm not OK,' it's going to be one of the scariest things you'll ever do, but it will be one of the best things you'll ever do." She soon started therapy. Now 17, Gracie shares her mental health story publicly and advocates for suicide prevention. An event she hosted in September drew 150 people.

City and school officials are also working to stem the rising death toll. Last spring, the El Paso County Public Health department hired a specialist to create a screening system to identify young people at risk.

But not all parents are willing to address the problem. Kelly, the medical examiner, says family members almost always request that his office cite a cause of death other than suicide, such as the choking game. "I've had relatives ask me if I would call it an autoerotic asphyxia because they didn't want to tell Grandpa that his grandson had committed suicide," he says. "That really speaks to what we as Americans think about mental illness." None of the obituaries for the Colorado Springs kids seem to mention suicide (a common omission everywhere), and it's unlikely that their memorial services included more than a vague reference.

Some worry that discussing suicide might inspire more kids to do it, but just because suicidal behavior can spread quickly doesn't mean it has to. Moutier, from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, says thinking suicide is contagious might give young people the impression that anyone can "catch" it, even a stable, happy kid. That's not true, she says.

Whether the parents of the deceased will admit it or not, suicide in most cases involves an underlying mental health condition. Researchers have found that if someone close to an adolescent dies by suicide, the adolescent's mental health history is a bigger predictor of future suicidal behavior than his or her relationship to the suicide victim.

El Paso County's most recent teen suicide was on September 19—a hanging on school grounds. Because teen suicides there tend to spike at the end of semesters—when students may feel as if they're losing whatever support they had at school, Kelly says—officials may not know until winter break if things are improving. Students aren't necessarily sending panicked glances around the classroom, wondering whom this plague will strike next. They have other things to worry about—exams, rehearsals, sports games, college applications. "When it first happens, that's all that is on everyone's mind," says Chloe Love, a junior at Discovery Canyon Campus, who does suicide prevention work. Then they move on. They have to. "Sometimes," she says, "the memories just hurt too much."

Sjoerdsma says she won't hide how Riley died. "I'm fully aware that my daughter committed suicide, and I don't know why." She has done social work, and her husband is a local middle school teacher; neither saw the signs. Since her daughter's death, she hasn't been sleeping well, and the spate of suicides makes the grieving process more difficult. At night, she often lies awake, thinking about how she and Riley used to say good night: "I love you here to heaven," Sjoerdsma would say. "I love you back to heaven," Riley would respond.

Sjoerdsma still says it every night. Only now, there's no one to say it back.