I’m at two deficit conferences Wednesday — CAP in the morning, on what to do about the deficit, EPI in the afternoon, about why we need to run deficits now. I’m trying to organize my thoughts; in this post I’ll talk about the EPI issue, in the next the CAP issue.

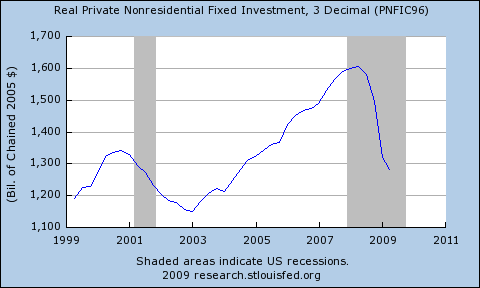

So let me start with a picture, which I’ll leave hanging for a moment:

Now for the discussion. Why, exactly, do we think that budget deficits are a bad thing?

The textbook answer identifies two reasons — two ways in which budget deficits now make us worse off in the future. They are:

(1) The fiscal burden: deficits now mean higher debt later, which will have to be serviced, and that means higher taxes and/or less spending on other, presumably desirable things

(2) Crowding out: when it runs deficits, the government competes with the private sector for funds, so deficits crowd out private investment, which reduces potential growth

All this makes sense under normal conditions. But right now we’re not living under normal conditions. We’re in a situation in which the economy is deeply depressed, and monetary policy — the usual line of defense against recession — is hard up against the zero-interest-rate bound. This weakens argument (1) — and it actually reverses argument (2).

On argument (1): it’s still true that an increase in government spending raises future debt. But not one for one: because higher spending raises GDP, it leads to higher revenue, which offsets a significant fraction of the initial outlay. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests something like a 40 percent offset is plausible, so fiscal stimulus only costs 60 percent of what it costs.

But the really dramatic difference is for argument (2). Under the kind of conditions we’re now facing, the main determinant of business investment is the state of the economy, as evidenced by the plunge in investment shown in the figure. This, in turn, means that anything that improves the state of the economy, including fiscal stimulus, leads to more investment, and hence raises the economy’s future potential.

That is, under current conditions deficit spending doesn’t lead to crowding out — it leads to crowding in. In fact, you could argue that the worst thing we can do for future generations is NOT to run sufficiently large deficits right now.

Things won’t always work this way. Eventually we’ll emerge from the liquidity trap, and the normal rules of economic prudence will reassert themselves. But we are not there, or anywhere close to there, right now.

Comments are no longer being accepted.