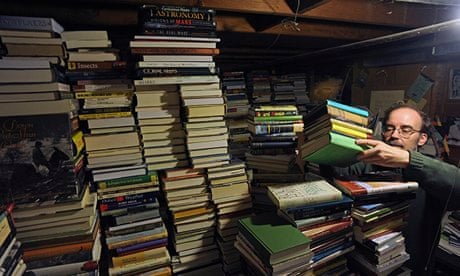

Too many books: they have to be culled. It's a cry that echoes through my house every few months, usually when a stalagmite of them topples on somebody's toe. The last cull involved packing my daughter's childhood into eight boxes – a melancholy task, cheered only by the willingness of her old primary school to take them, sight unseen, for the Christmas fair. This time, more drastic action was needed. Instead of riffling through the piles on the floor, I decided to work from the top.

Up on the most inaccessible shelf, where the cobwebs join ceiling to wall, was nearly three foot of reclaimable space, aka the collected works of Charles Dickens.

Now I love Dickens, and wouldn't be without copies of Bleak House, Great Expectations and David Copperfield. But the ones I actually read – have ever read – are in handy paperback editions. When my husband decided to make Barnaby Rudge a holiday project, he downloaded the Project Gutenberg text to his iPad.

So what is the value of the 16-volume edition that somehow found its musty way to me from my grandparents' flat many years ago? These are books that aspire to be furniture: published in the early 1930s by Hazell, Watson and Viney, they're the colour of polished mahogany with gilded curlicues that might grace the chambers of the lawyers pursuing Jarndyce v Jarndyce. It's nice to see the original illustrations, but the text itself is too cramped and faded to be easily readable. These volumes have the lurky-murky smell of books that have lurked too long in the murkier depths of secondhand bookshops.

This isn't the first time I've considered getting rid of them, but two obstacles have always stood in my way. The first is the inscription in my grandfather's handwriting from 1933. I hate the idea of books as furniture, a fetish unforgettably skewered by F Scott Fitzgerald in the third chapter of The Great Gatsby. But there's a biographical poignancy to the idea of my grandparents filling the shelves of their new home with brown Dickens, red Macmillan pocket editions of Kipling and red and green Loeb Classical Library volumes, which I find hard to resist. Unlike Gatsby they did, at least, cut the pages.

The second reason I am reluctant is more pragmatic: how do you dispose of a yard of old, but not antique, books? Libraries aren't interested in secondhand books, and the several collections already on offer on eBay – most at less than £50, buyer collects – don't seem to be making a dash for the door.

Bibliophile Gillian Thomas captures my ambivalence in her blog, The Afterlife of Books: "That books outlive their authors is a consoling thought. That they outlive their readers evokes the opposite reaction." Their desolate fate reminds her of Tony Harrison's poem Clearing,

The ambulance, the hearse, the auctioneer

Clear all the life of that loved house away.

The hard-earned treasures of some 50 years

Sized up as junk and shifted in a day.

Perhaps I'll put these ones back on the shelf. Just for now.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion