Despite the dramatic changes in gender norms in the last few decades, there is one domain where men have steadfastly refused to make tremendous gains: Chores. Wives who are primary breadwinner in the house? Hardly unusual. Husbands who are passionate closet-organizers? Rarer specimens.

This might not be a problem requiring a national solution, but Stephen Marche writing in the New York Times, has one anyway. "The only possible solution to the housework discrepancy is for everyone to do a lot less of it," he writes.

Hm, maybe. But also, how convenient. Wives want cleaner homes; husbands don't. And the "only possible" compromise solution is that the guys get exactly what they want?

This is the third article I've read on the subject of men and housework, after Jon Chait (asking women to embrace the dust) and Jessica Grose (asking men to embrace the duster). Without trying to sound like a cop out, I'll just say that I have no idea how all 120 million married couples should divide their responsibilities. But here are three facts about housework and married couples that should probably drive the discussion:

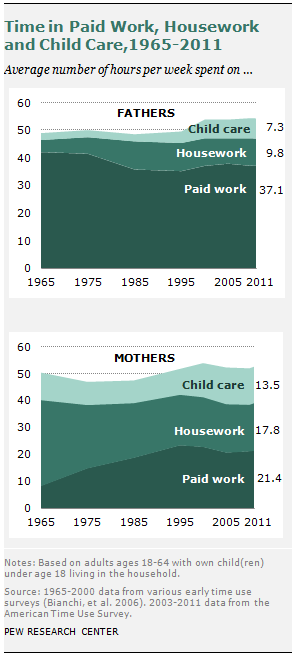

- There's less and less housework to do: The amount of housework has declined by 23 percent in the last half century, according to the American Time Use Survey, which is the gold standard for measuring how we spend our days. Some of this decline might be dirtier houses. Much of it is new technologies, like better washer dryers and vacuums, that save time.

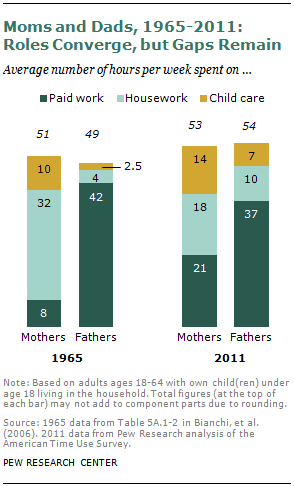

- Men do more of it than they used to: They've more than doubled their share of housework since the 1960s.

- But women still do most of it: 18 hours a week for mothers vs. 10 hours a week for fathers in the 2011 ATUS.

Here's the graph that most people use to begin this conversation. In the mid-20th century, parents specialized. Dad worked for money. Mom worked at home. But as more moms went into the office, men took on more of the chores and child care.

The pendulum has swung, but, as Marche notes, it's also stopped mid-swing. Dads do less housework today than they did in the 1980s. Moms and dads (especially the affluent) spend more time with their children now and less time cleaning up, possibly because of breakthroughs from Whirlpool, Swiffer, and other home-tech companies have made chore-time more efficient. (Indeed, the whole debate would go away if robots just cleaned our homes for us.)

Marche and Chait both note that their wives' instinct for a cleaner, less dusty floor seems quite nearly genetically programmed, and it is a male/female divide that simply cannot be breached. It's plausible that women do more housework because they tend to prefer cleaner homes. But it's also plausible that they grow up expecting the role of housework to fall to them. The American Time Use Survey suggests that men do 35 percent of total household tasks, by time. But only 2 percent of commercials for home-cleaning products show men doing the actual cleaning. Mr. Clean is a fine mascot, but as an aspiration for men, his influence is as real as his skin.

Housework is often about more than housework ("I want you to want to do the dishes," and so on). A cool paper by Marianne Bertrand, Jessica Pan, and Emir Kamenica found that wives earning more than their husbands are more likely to be unhappy in the marriage, more likely to feel pressured to take fewer hours, more likely to get divorced, and more likely to do significantly more chores around the house.

This makes no sense at first. "Classical economics can't explain that increase," Kamenica said. These women are utterly starved for time, so why are they also cooking and cleaning? He chalked it up to "compensatory behavior." The wife does more of the cooking and cleaning to make the husband feel okay that he's earning less. The housework division isn't always about who wants a cleaner floor, or where the magazines should go. As a symbol for shared responsibilities in a relationship, it's not the sort of thing that can be solved by Marche saying let's all just learn to love filth.

So, yes, we could all do with slightly dirtier houses, and nobody ever died saying their only regret was they didn't buy enough ceramic tile cleaner. But maybe, now that women are out-earning us in bachelor's degrees and (often) in marriages as well, we could stand to do oh-just-slightly more than 35 percent of the dishes.