Business, citizens and governments might take the internet for granted today, but digital assets could soon fall into an abyss causing irreparable social and corporate memory loss.

That’s the take from father of TCP/IP, Vint Cerf, who’s railing hard against the modernist urge to purge.

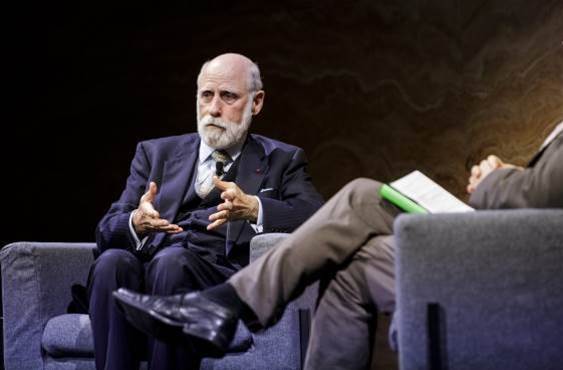

Speaking in Sydney on Wednesday, Cerf issued a blunt call to action that a digital preservation regime for content and code - especially on the web - must be quickly put in place to counter a throwaway culture that will deny future generations an essential window into life in the past.

“We have a big problem. I call it the digital dark age,” Cerf warned a presentation organised by the UNSW Engineering faculty and Google.

“We don’t curate our digital content with much care and until we realise that, we can’t get any of it. It’s gone, we can’t read any of the bits anymore.”

Function beyond format

The internet’s big pitfall, as Cerf sees it, is that as technology evolves and changes, everything from photos to documents, records, applications and social media could cease to be functional in as little as a decade, as old formats and standards are superseded.

It’s not so much the end of history - rather its that the file format is no longer supported and no one bothered to keep a back-up. But there is a recovery plan.

“I’m a big fan of a project to create a regime in which we can assure ourselves the digital content that has meaning to you and to me and to others is still readable.”

World’s biggest back-up fail

There’s a lot more at stake than just preserving the past for the sake of it, too.

Cerf told iTnews he believed there were implications for future technological development and breakthroughs - think software development – if access to what has already been created is lost.

“It’ll harm our ability to take advantage of what we know and have created if we can’t get access to it," Cerf said.

“The regime that should be in place [is] one in which old software is preserved, hardware can be emulated in the files so we can run old operating systems and old software so we can actually do something with the digital objects that have been captured and stored."

The assets at risk are inherently tangible, not theoretical.

“Think of all the papers we read now, especially academic papers that have url references. Think about what happens 10, 20, 50 years from now when those don’t resolve anymore because the domain names were abandoned or someone forgot to pay the rent.”

History pronounced DOA

While the digital disappearance phenomenon is one which has so far mainly vexed official archivists and librarians for some years now, Cerf’s take is that as everything goes from creation, the risk of accidental or careless memory loss increases correspondingly.

Archivists have for decades fought publicly for open document formats to hedge against proprietary and vendor risks – especially when classified material usually can only be made public after 30 to 50 years, sometimes longer.

UNSW Scientia Professor of Artificial Intelligence, Toby Walsh, pressed Cerf on whether DOA (digital object architecture) will solve the digital dark age dilemma.

Cerf responded that while this was what his partner in TCP/IP’s development Bob Kahn was trying to do 20 years ago, it only solved part of the problem.

“The specific problem with urls can be solved with DOA,” Cerf said. “It gives a label which should be permanent, that’s what Bob Kahn was trying to do.”

But where to keep assets is another issue.

“If all the resolution process needs to be maintained for a long period of time, someone has to store the data somewhere,” Cerf said.

“It still has to be retrievable and it still has to be interpretable and some of the other things.”

Life after 404? Ask Archimedes

Cerf especially lauded the efforts of Brewster Kahle of the Internet Archive over the last 20 years before offering a salutary lesson in what happens when invaluable documents are lost before their significance or impact is understood.

Enter Archimedes of Syracuse of mathematical fame from ancient Greece.

“Archimedes wrote some things about count computation [around] 300BC. These were lost. A good friend of mine purchased the palimpsest and went through a huge amount of trouble to get the Greek out of [the vellum which] had been erased,” Cerf said

Drawing his fingers closer together to illustrate, Cerf said that “Archemides was this far away from the calculus. He was talking about infinitesimals in the same way that [Isaac] Newton did in the 1600s."

The loss was that around 2000 years passed before Archimedes’ calculus was rediscovered.

“What if we had that?” Cerf argued. “That was preservation by accident. This is not a plan.”

.jpg&h=271&w=480&c=1&s=1)