Helen Czerski has the coolest job in science – she’s a bubble scientist. Or, to give her her full title, she’s a physicist and oceanographer at University College London. When she’s not doing that, you’ve probably seen her on telly as a science presenter for the BBC. She has just finished her first book, Storm in a Teacup: The Physics of Everyday Life, and if that’s not enough she also plays badminton competitively. Sitting at her kitchen table, just returned from a morning coaching session and still wearing her racket club’s black and red polo shirt, she laughs as the Observer opens with the obvious question…

Bubbles?

Yeah, nobody quite knows what to make of it when I tell them, but they’re always interested. Bubbles are like the dolphins of the physics world, right? They make people happy. But scientifically they’re also fascinating. They’re in champagne, they’re used in medicine, they’re in the ocean – they’re the unsung heroes of the physical world. This business of having two phases together – a liquid and a gas interacting – is such a useful thing. It gives you something that neither a gas or a liquid can do on its own.

Like what?

Take the foam on top of a cappuccino. It’s just milk and air. Put a spoon on top of a column of just coffee or just air and it’ll fall through, but whip them both up into a cappuccino and the spoon will rest on top. Understanding what’s going on when bubbles form has all sorts of applications, like understanding how oceans breathe or how light and sound travel through oceans.

Why do people need to know about the physics of everyday life? Isn’t it just good enough to know that things work, like a smartphone?

It’s about knowing the rules of the world so you don’t get exploited. Whether it’s a politician or a salesman, you need to know the rules they’re playing by. It doesn’t mean you have to be an expert on weather systems or on double glazing or cars or mattresses or phones, but if you know the basics it gives you the confidence to ask the right questions. Say someone is trying to sell you a swanky smartphone case to make your reception better, or a magnetic bracelet they say will cure your wrist pain, you can ask “well, how does it work?” and if you know the basics you can tell whether they know what they are talking about or whether they’re just making things up.

But a lot of people shun physics because it seems so complicated and irrelevant.

I know. I don’t think we’ve done a good job in talking about physics. People get the impression that it’s all about quantum weirdness or stars and time and the universe, but it’s also about quite basic things. Physics is about patterns that are folded into our everyday lives. It’s much more accessible than people think and we should be telling them that. But nobody else is, so I am.

Do you have an example from your book?

OK. How about the way that tea sloshes around when you walk helping to explain why mobile phone signals don’t interfere with each other? Tea sloshes at different rates in different size mugs, faster in little mugs and slower in bigger ones. The reason you spill tea when you walk is that it just so happens that the walking speed of a normal human is almost exactly the same as the slopping speed in your average mug. The walking speed exactly reinforces the slopping speed, so you spill the tea if you walk normally – walk slowly or with a tiny mug or a gigantic mug and you won’t spill a drop. Mobile phone signals work on the same principle. They’ve each got a really precisely tuned resonance – or electron slopping rate – so that you can have two people sitting next to each other on two phones having two different conversations and they won’t interfere with each other.

Is there a tension between being a scientist and being a television presenter?

The biggest tension is time. It’s definitely more than one job, however you want to add it up. There are benefits: I learn a lot. I’ve definitely met people and learned things that I otherwise wouldn’t have if I stayed in my lab like a lot of scientists do. There are similarities between the two, too. The most important thing, whether it’s doing scientific research or presenting or writing, is understanding the situation clearly enough to be able to pick out exactly the right question. To organise all the ideas into a hierarchy and say: “This [jabs at an imaginary point with her finger], this is the important thing that it all hangs on.”

It must be tough to make time for yourself?

Not really. I manage to do some kind of sport – badminton or running or canoeing – almost every day. One of the things that I find mystifying is that people tend to think of scientists as somehow “other”, somehow alien. I’ve sometimes not been invited to normal, mundane things that I’d enjoy because people assume I’m off doing something higher. It’s true that I read a lot of books and play with ideas but the washing machine breaks for me, too!

So what’s your biggest non-science, non-sport guilty pleasure?

I guess I’m not allowed to say reading, am I?

No.

Erm… chocolate. Dark chocolate with hazelnuts.

Of what are you most proud in your career?

Overcoming being extremely shy. I was too shy to speak as a child and it’s something I only really began to overcome around the time of my PhD [in experimental explosives physics at the University of Cambridge]. Academically, I’m probably most proud of building instruments that go out into the open ocean and measure things that we have never been able to measure before. There’s something quite satisfying about drawing a ridiculous machine on a piece of paper and then a few years later having this monstrous thing sitting in front of you, pushing a button and it working.

If money or logistics were not an issue, what would your dream experiment be?

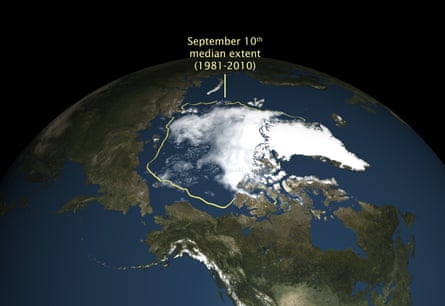

I’d like to go to the Arctic and study the bubbles underneath breaking waves there. As the sea ice retreats the Arctic Ocean is becoming more and more exposed, so we need to understand better how gases and particles are exchanged across it. Bubbles are the vehicles that allow this exchange. Finding out what keeps us and our planet alive – and what might not keep us alive – is becoming increasingly important.

Science is all about evidence and acting rationally. What is the most evidence-free or irrational area of your life?

I suppose I’d say I was a compulsive opportunity taker. I see choosing to have an adventure as a rational decision, even though it might look irrational to others.

So if someone asked you to go on a one-way trip to Mars to study bubbles you would go?

I feel like I’ve got a bit more living to do on Earth first. Anyway, nobody’s solved the radiation problem yet. If they figured out a way to send people there without giving them incurable cancer then I’d think about it. I reckon I’ve got at least another two or three decades before it becomes a possibility.

Hang on, are you saying that the Mars One expedition is not going to set up a colony on Mars by 2027 like they say they will?

You see! Knowing some basic physics can help you make important real-life decisions. [laughs]

Storm in a Teacup: The Physics of Everyday Life by Helen Czerski is published by Bantam, £18.99.Click here to order a copy for £15.57

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion