Upworthy: I Thought This Website Was Crazy, but What Happened Next Changed Everything

The Internet's latest viral wizard matches smart technology and lily-white earnestness to market "stuff that matters" online, and the Gates Foundation is buying.

The first blockbuster hit came from an unlikely source: Irish talk radio.

In 2010, Michael D. Higgins, then a foreign-policy spokesperson for Ireland (and now its president), went on the radio in Galway and excoriated a conservative American talk show host for opposing President Obama's plan to enact universal health care. For a long time, the audio file of the berating lingered in Internet purgatory. Then, in August 2012, Mansur Gidfar uploaded the audio to the new, rapidly growing site Upworthy.com in August 2012. He tried the headline, "A Tea Partier Decided To Pick A Fight With A Foreign President. It Didn't Go So Well." The article went certifiably berserk, eventually becoming the site's first million-hit story.

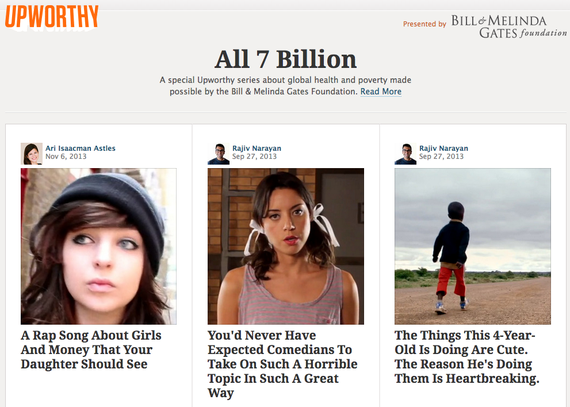

Today, Upworthy is a million-hit machine for heartfelt, progressive content, and it is trying to use this alchemy—spinning hearty fiber into viral gold—on behalf of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. On Tuesday, the company announced it is launching a global health and poverty section backed with Gates money, suggesting a future for not only the site's editorial strategy but also for its business.

Upworthy has mastered the dark viral arts with a unique blend of A/B technology and lily-white earnestness. The staff scours the Web for "stuff that matters," writes multiple headlines for a test audience, selects the top-performer, and blasts it out on social media. It's a deceptively simple plan that's devouring the Internet, one Facebook Newsfeed at a time. The site nearly surpassed 50 million unique visitors in October, which suggests traffic comparable to giants like Time.com, and Fox News.

Upworthy has run paid content, like a Microsoft-sponsored video of a Ugandan man talking to his family over Skype. But this is the first time that an organization like the Gates Foundation has paid to popularize a particular concept like global health and poverty. In a way, the partnership harkens back to Upworthy's founding idea to be a bullhorn for non-profits, amplifying their research and message, and then taking a cut. This pilot partnership will provide one full-time "curator" to trawl the Web for stories about toilets (Everyone Poops, But 2.6 Billion People Do It In A Really Crappy Way) and global disease (When Future Generations Look Back On Us, They'll Say We Had The Opportunity To End 3 Awful Epidemics).

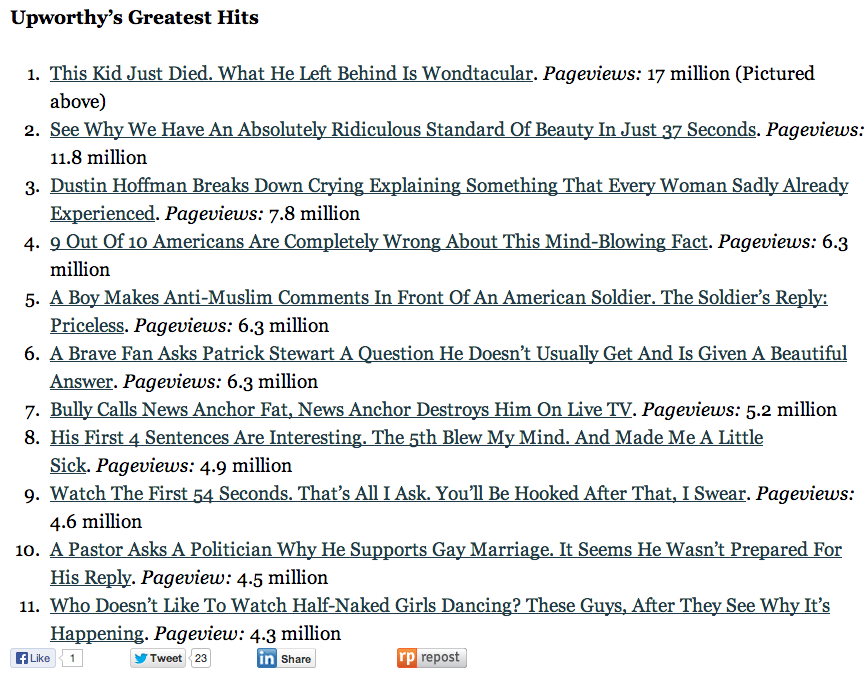

... And Made Me a Little Sick

Upworthy's vertiginous success isn't without criticism. The site's pleading, occasionally histrionic, gooeyness has inspired criticisms of so-called "glurge" and a popular parody account, @UpWorthIt. Here, for example, is a list of Upworthy's 11 greatest hits, whose pageviews are downright otherworldly.