Trauma

Have I Been Traumatized?

And is there something that I can do about it?

Posted August 30, 2016

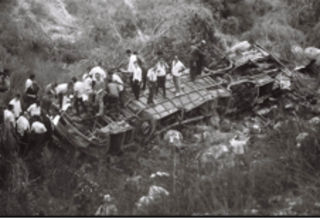

On July 6, 1989, a crowded commuter bus, traveling from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem was run off a cliff into a steep ravine. The perpetrator seized the steering wheel, turning the bus off the road in a split second. The bus rolled three times, disintegrated and took fire. Fourteen passengers died. Those who survived were ejected from the windows. Many were injured. Sixteen survivors were admitted to Hadassah Hospital where Shaul Schreiber, MD, Tamar Galai, and myself followed them daily, listened to their accounts of the incident, met their families and recorded their symptoms1, 2.

Per DSM-III PTSD diagnostic criteria, the Bus 405 incident was a trauma par excellence: an event "outside the range of normal human experience" that "would be markedly distressing to almost anyone." However, not every survivor considered himself or herself "traumatized."

M., a small middle-aged woman managed to pull her nephew from the rubble before the bus took fire. She was exuberant: “Me, subdued daughter of Holocaust survivors, acting swiftly when trouble comes my way? I didn’t know that I had such force!” She didn't develop PTSD symptoms.

Her nephew, a young athlete, suffered a hip fracture. Yet even more painful was his recollection of seeing the assailant jump on the driver and not reacting in time. He could not get that image out of his mind.

A female professional who recently moved to Israel sustained a spinal cord injury and was paralyzed from the hip down. She dryly summarized the situation as follows: “I just started my life here, and here I am, part of the country’s history.” She did not survive. Finding her bed empty when we came to see her in Orthopedics broke our hearts.

Another female survivor convinced an ER employee to stop at a public phone, on their way to radiology. She called her husband and summoned him to prevent the media from reaching their daughter before she competed in a sports event that evening. “From that point on, I felt on top of things” she said. Shaul kept seeing her for years. She did very well, though once in awhile, e.g., when a plane gets into an air pocket, she is back in Bus 405 for a few seconds.

We learned from another survivor that intrusive recollections are not always consolidated memories of the traumatic event, but often those with intolerable meaning: She wasn’t going to take that bus because it was full, but as she hesitated a young person invited her in, and helped with her bag. That person was the assailant. His smiling face as he helped her board the bus was her torturous intrusive recollection of the event.

People react to trauma in many different ways. They bring their personal history to the event, actively cope to reduce trauma’s impact, protect close friends and relatives, negotiate ways out of trouble, and find ways to gain mastery and preserve dignity: A hip-fractured young tourist, lying on a makeshift stretcher, dictated phone numbers to the rescuers who pulled her out of the ravine, lest she faint and become “unidentified.” Another injured survivor asked us to first take care of her father, who had just recovered from a mood episode. The one adolescent in the lot, a female, was virtually unreachable: Her family surrounded her hospital bed at all time, giving us, caretakers, a sense of intruding into a ‘family-only’ event. I remember watching her and her family, sensing their tenderness, love, and soothing relationship with their daughter and thinking that she already had the best caretakers.

Highly distressing events are common, and those exposed—survivors, witnesses and helpers—may often wonder how being there might affect their lives. Our current lexicon unfortunately associates such events with the very problematic term “trauma,” which also implies a likelihood of “post-traumatic stress disorder”—a mental disorder. Survivors’ question, thus, often becomes “Have I been traumatized?” with an underlying flavor of something happening to me out of my awareness and control, involving genes, stress hormones, brain circuits and what not. A bad reaction, likely to lead to bad outcome via yet unknown—though very complex processes that only learning machines can fathom.

Moreover, while “have I been traumatized” is a personal question, research to date explores average group probabilities and uses standardized psychometric instruments that capture common dimensions of behavior. Not surprisingly, research to date does not allow individual prediction. More recently, machine-learning algorithms are crunching the same standardized data, yielding much higher levels of abstraction—nothing personal.

Forgotten are individual narratives and metaphors, that is, the most powerful modifiers of people’s understanding of events and predicting their consequences. I believe that to better understand trauma we should return to survivors’ accounts.

What can the Bus 405 narratives teach us? Rather simple:

For caretakers: Survivors’ stories will surprise you if you care to respectfully ask and then listen. Only, we, pros, have developed a habit of not asking. We know. Survivors are traumatized! They are victims. They are at risk. For their own sake we need to count their symptoms, evaluate (though without good evidence) the likelihood of them being permanently affected, offer treatment or otherwise intervene using one cookbook or another. At the utmost end of insensitivity, some professionals discuss forthcoming PTSD symptoms with survivors or provide lists of PTSD symptoms that, ironically, are both “normal” and “risk indicators.” This is not very helpful: It models survivors’ reactions and focuses their attention on the least relevant post-exposure issues. Furthermore, to the extent that enquiring about symptoms eclipses soothing human contact—sharing emotions, getting a survivor either cold or room temperature water, or soda (just ask; a survivor may have a preference) or addressing sources of tension, however minimal—we miss the point.

For survivors: What these stories tell us is that being "traumatized" is mitigated by small victories, by gaining control over however small a portion of the event and its aftermath, by allowing soothing human contact to reach us, and by safeguarding our attachment bonds. The idea that you passively develop post-traumatic stress symptoms, given genes, or hormones, or brain circuits is plain wrong. Genes, molecules etc. account for a small portion of illness likelihood. Bad genes might make the struggle out of trauma a bit harder. But you had those genes throughout life, and must have already experienced a recovery from stress and thus have already developed strategies to mitigate their effect.

Scenes of horror are likely unforgettable. Nonetheless, they can either dominate the rest of your life or merely add a layer of painful memories, accessible at anniversaries and memorials. Scars versus open wounds: That’s the choice that trauma imposes. To tilt the balance toward the better outcome, you should know that (a) there is no such thing as totally passive victim, and thus you will always cope with stress, one way or another, (b) the worst thing that traumatic events might lead you into is passivity and disconnection with other people, (c) uncontrollable emotions (fear, disgust, despair, horror) are transient, (d) there are always parts of reality that you can negotiate and eventually control, (e) small victories lead to major inner changes and (f) soothing human contact, whether conveyed by words, touch, eye contact or by arranging your bed sheets, can and will re-arrange your post-exposure physiology, genes’ activity and neuronal transmission. Unlike being wounded physically, psychological trauma can be mitigated by who we are, who is around us, how we perceive and shape our responses and what we do.

References

1. Shalev AY, Schreiber S, Galai T. Early psychiatric responses to traumatic injury. Journal of Traumatic Stress 6:441-450, 1993

2. Shalev AY. Posttraumatic stress disorder among injured survivors of a terrorist attack: Predictive value of early intrusion and avoidance symptoms. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 180:505-509, 1992.