At 3am outside the BP petrol station in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, the January sky was still black, but the solitary garage attendant was already serving migrant workers. By 4.15am, dark and silent figures crossing the town had become a steady flow towards the light of the pumps on Freedom Bridge roundabout.

Summoned by a text late the evening before, they huddled in threes and fours on the edge of the forecourt, waiting for a succession of vehicles that would take them to shifts lasting between 10 and 12 hours, in fields and factories across the region. The mumbled greetings were almost all in Latvian, Russian or Lithuanian. Three old vehicles pulled in to fill up with passengers and petrol, and then set off. Those still waiting shared cigarettes and shifted from foot to foot in the Fenland frost. Not long after, a blue BMW with a Latvian number plate cruised into the station, thumping out a bass track loud enough to shake the ground and wake the whole street. A police patrol car appeared, ran slowly round the roundabout and drove off, back the way it had come.

DCI Donna Wass had seen this happening since the spring of 2013, when she was transferred into the area because of her long experience investigating organised crime. Wass had a clear view of the BP garage from Wisbech police station, which was on the same roundabout. She had observed the same pre-dawn routine over and over again. While houses in the small market town still had their curtains drawn, the garage served as an unofficial labour exchange.

A web of several competing eastern European gangmaster operations hiring out migrant labourers seemed to be connected to an increase in crime – although it was politically charged to say so. There had been a spate of apparent suicides among young eastern European men who had come in search of work – five within a year between 2012 and 2013. Three of the dead had been found hanging in public places around the town; one of them had been recovered from a small park near the BP garage next to graffiti that translated as: “The dead can’t testify”.

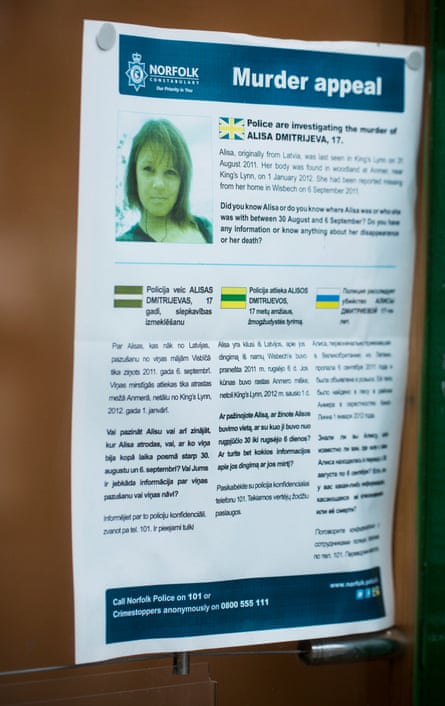

These were not the only disturbing deaths: a 17-year-old Latvian girl had disappeared from Wisbech in the summer of 2011, and her partially clothed, decomposed body was only discovered five months later, on the Queen’s Sandringham estate. A Lithuanian courier was killed in an arson attack on the van in which he was sleeping. There had also been reports of knife attacks by migrants on migrants but victims would disappear or turn out to have been using false identities.

By summer 2013, it was clear that the scale of criminal activity would require more resources. Wass was joined by a second senior investigating officer acting as her deputy, DI Jenny Bristow. Intelligence suggested they were looking at between five and seven organised crime groups operating in and around Wisbech, all involving foreign nationals and migrant workers.

The BP garage was one of the places Juris Valujevs liked to do business. Sometimes the 36-year old Latvian would come in his gold BMW to explain how things worked to new recruits from the Baltic States. Sometimes he would sit in another car, a Mercedes, while his associate Ivars Mezals did the talking. Mezals was regularly seen at the petrol station in the small hours, directing dozens of Latvians and Lithuanians into cars. The deal Valujevs and Mezals offered their fellow migrants was simple: we will find you casual work, in a field or a factory, but only if you live in the rooms we rent to you, travel in the transport we charge you for – and sometimes, do a few more things on the wrong side of the law.

It was uphill work for the police to persuade the eastern European community to speak to them about the gangs. Warnings not to talk to the police had been daubed on a wall in the style of threats made by the Russian mafia. Wild rumours had circulated that another young woman had been murdered behind the BP garage and left with her tongue ripped out. (When police investigated, the gossip turned out to be false, but it had the intended effect.)

The endless procession of 44-tonne juggernauts hauling past the BP garage day and night offered a clue as to why this quiet rural town had become a hub for crime. The Fens – the bleak, marshy flatlands of East Anglia – produce more than a third of the UK’s vegetables and are a powerhouse of agricultural exports. The constant “just-in-time” replenishment of goods at the heart of today’s retail and manufacturing business models requires an equally constant replenishment of workers, ordered at short notice. To turn labour on and off like a tap you need a surplus, just waiting for the late-night text, desperate enough to take 12 hours’ work one day, and nothing the next. That pool has itself required constant replenishment with new arrivals of changing nationalities, in repeated waves of immigration, since only the newly arrived or the vulnerable will put up with the conditions.

The Portuguese and Polish migrants who came to the region more than a decade ago have mostly moved on from farm and factory work to more integrated lives in Wisbech and elsewhere. They were among the early EU migrants, who replaced the Afghan and Iraqi-Kurdish asylum seekers who dominated the labour supply before them. In recent years, gangmasters, agents who supply workers to factories and farms, have recruited flexible labour from the poorest rural areas of the former Soviet bloc. Currently it is Latvian, Lithuanian and ethnic Russian migrant workers who are desperate enough to endure the low pay and long hours. Lured by the promise of good work, often speaking no English, they have been easy to exploit.

Most of us do not see the brutal parallel universe at the heart of the mainstream economy. But in the Fens, it has been highly visible – along with the transnational organised crime running a part of it. This has made people very angry. Now they want out of Europe – more than two–thirds of voters in Wisbech’s parliamentary constituency said in a 2014 survey that they would favour the UK leaving the EU.

The scene that plays out at the BP garage each day is not simply about migration or the human cost of cheap goods or isolated rogue operators. It is the manifestation of a profound social and economic change that has been enacted in little more than two decades.

From the late 1980s on, new technology allowed employers to eliminate much of the financial risk from their end of the chain. Supermarkets, for example, only reorder stock when a customer buys an item and its barcode is scanned, generating an instruction to their suppliers to replace it by the next day. Orders can double or halve within 24 hours, so workers to process and pack the goods are called in at short notice. This reduces costs and increases profits, since businesses no longer have to keep inventory or pay for full employment. Instead they have outsourced labour provision to agents or gangmasters. Agriculture and food processing pioneered this lean approach to business, but its zero-hours practices have spread to other sectors – to care homes, catering and food service, hotel work, cleaning, construction, and personal services such as nail bars and car washes.

Earlier waves of migration brought foreign workers to other East Anglian towns, but the availability of cheap housing has drawn gangmasters more recently to the Wisbech area. The last census of Wisbech in 2011 put the population at around 25,000 but officials accept that it is now probably nearer 30,000, with about 10,000 of those people recently arrived foreigners. The size of the private rental market doubled in a decade to more than 2,000 properties in 2015. Houses of multiple occupancy (HMOs) – the gang-run houses where new migrants mostly live – now account for a substantial percentage of housing stock. Government agencies trying to reach vulnerable migrant groups visited around 500 homes in the year from January 2014. By then, three of Wisbech’s wards had become some of the most deprived areas of the country.

Blaming immigration rather than the forces that drive it, local people have turned to politicians who promise to curb it. In 2013, Ukip won all four Wisbech seats in the county council elections. There have been tense anti-immigration protests in the town. Both communities felt under attack – eastern Europeans remember how a gang of local teenagers beat up two members of their community in 2006. English residents I met were quick to say that they no longer felt safe or at home in their own town.

Valujevs was short, with closely cropped receding hair and a gym-worked neck and frame. When I first met him he wore a white silk scarf with designer black quilted jacket, collar turned up. There was something vaguely Putinesque about his demeanour: he was courteous but unsmiling. People said they were afraid of Valujevs; police noticed that fellow migrants would step into the road to let him pass.

Mezals, a 28-year-old Latvian mechanic, was from Valujevs’ hometown of Balvi, near the Russian border. He cultivated a more cheeky, cheery persona, unless he had been drinking, when he could become threatening. Much taller, he wore a gold chain under his sweatshirt, and black jeans, but had the same close-cropped hair, the same slightly bow-legged strut. His designer statement was a Versace watch. People felt intimidated by him too, and spoke his name in a whisper.

As required by law, Valujevs had applied in 2008 for a licence to operate as a gangmaster from the Gangmaster Licensing Authority. He was rejected, but carried on regardless, working below the radar for years, recruiting migrants and, with Mezals, supplying them illegally to other licensed gangmasters – some eastern European, some English. They in turn sent them to jobs cutting broccoli, cabbages, and daffodils, pulling leeks, onions or potatoes, or grading and wrapping vegetables in packhouses for some of the UK’s largest industrial farms, which supply our major supermarkets.

The key to Valujevs and Mezals’ operations was renting and then subletting property. They would place eight, sometimes even 12 people in a small house, charging them £50-60 a week each, even when the workers slept three or four to a room on mattresses on the floor. The amount of work the migrants were given appeared to be rationed so that they constantly fell behind with rent, and got into debt to Valujevs and Mezals. This gave the two men a hold over them. They controlled about 40 workers at a time, in half a dozen overcrowded properties, but since the houses were mostly registered in other names, it was hard to count precisely.

Valujevs and Mezals also had a lucrative business buying up scrap cars at auction. Mezals would fix them or break them up for parts outside the Wisbech houses the pair sublet, driving the English neighbours mad with the noise and the mess. They would get orders for the flash cars from Latvia and Ukraine, while the cheaper vehicles were used to deliver migrants to their work in remote areas. They charged each occupant £7-10 in fares, even if, as repeatedly happened, the migrants were summoned by employers to work at dawn, only to be told on arrival that there was nothing for them that day.

Some workers who were recruited in Latvia on the promise of regular work were already in debt for their air fares when they arrived, carrying suitcases of cigarettes they had been given to smuggle. Others were recruited locally, including three Latvian alcoholics who had previously been sleeping rough next to the Wisbech Tesco carpark, and using the supermarket’s toilets to wash. An acquaintance had sent them to Mezals at the BP garage. Mezals and Valujevs took them to one of their crowded gang houses and provided them with food, toiletries and work – just helping people, they said, from their own tight-knit community.

Friday was payday and there were often rows and sometimes fights. Mezals and Valujevs would do a rent and debt-collecting run around their Wisbech lettings. Workers complained that their calculations of debt were arbitrary. Sometimes Mezals collected the migrants’ wages himself from the gangmasters, illegally taking cash directly from wage packets, so that workers were often handed just £20 after a week’s hard labour. Sometimes Valujevs and Mezals would drive workers to a gangmaster’s office and wait outside while they collected their money, then make them hand over most of it as soon as they got back into their vehicles. You learned to hide some of your earnings in your bra, one worker said.

A number of other eastern European suspected organised crime groups in the area appeared to have the same modus operandi. Without effective enforcement the system spread. Valujevs and Mezals had learned how to exploit migrants through being exploited themselves.

Valujevs came from Latvia to work in England in 2003, shortly before EU enlargement opened up the labour market to eastern Europe in May 2004. He had spent time in prison in Latvia for drink-driving and theft – as a juvenile he had stolen metal from public wiring to sell.

He started his life in the UK on the bottom rung, harvesting vegetables through the winter in muddy East Anglian fields, often enduring the penetrating damp from 6am until 8pm. He worked for a company named ELS Recruitment. Its managers threatened, intimidated and verbally abused their eastern European workers, deducted money for transport from their wages, controlled where they lived, how much work they were given and whether they got paid. Its staff pulled leeks that ended up on shelves in Sainsbury’s at the time. The industrial farming company, the packhouse owner and the supermarket that made up the subcontracted chain all said they were shocked by the “unacceptable” conditions. The Gangmaster Licensing Authority shut ELS Recruitment down in 2008 for abusing its staff. Even though the company’s licence was revoked, no prosecution was ever brought, and none of the workers’ lost pay was ever recovered or returned.

Valujevs moved on to another gangmaster in the Fens, an Englishman called Martyn Slender, offering himself and fellow workers. Slender had his own method of cheating the migrant workers he was supplying at the time to Asda’s leek producer, Nightlayer Leeks. He fiddled their timesheets so that it looked as though they were being paid the legal minimum wage per hour, when in fact he was defrauding them of half of it.

Valujev’s wife, Oksana Valujeva, also did long shifts cutting cabbages and picking daffodils. She was originally from Belarus, which is not part of the EU, so her immigration status depended on Valujevs. She was as slight as a sparrow, her face often flushed beneath her bleached blonde hair. She sometimes drove workers to their jobs or collected new eastern European arrivals from the airport. In between, she looked after the couple’s young children, who went to school near their home in King’s Lynn, Norfolk. At 34, she looked worn out with work and worry. Valujevs had been seen by a local resident smashing her head into his car in 2010. He was taken to court by police, but she offered no evidence and he was simply bound over to keep the peace.

Valujeva was inseparable from her Latvian friend Lauma Vankova, who had started out in Wisbech working the vegetable and flower harvests, and later moved to King’s Lynn. Vankova was younger – 26, defiant and full of energy. She could be demure or flashy, wearing little collars and woollens with appliqué one day, then black lace tops with a Paris Hilton handbag the next.

Vankova had arrived in the UK around 2008, with young twins from a previous relationship. She and Valujeva shared everything, including childcare. They even shared Valujeva’s husband, it was claimed, when compromising pictures of them were found on a memory stick. This was around the time that Vankova had flown with Valujevs to Azerbaijan to marry a man she had met online through a Russian “lovemail” website. None of her family or friends had been there for the wedding. When her Azerbaijani husband applied for UK residence as the spouse of an EU national, UK immigration challenged the legitimacy of the marriage, but on appeal, a judge had ruled the relationship genuine. Vankova’s new husband moved to England, but did not live with her. Knowing how to negotiate UK immigration rules would later prove to be profitable, when she and the Valujevs began organising sham marriages.

Mezals was just 18 when he decided to take his chances in England in December 2004. He was living with his mother in the Latvian capital Riga, and although he had spent three years training as a mechanic, could not find work. He had ended up in a scrap yard instead, earning the equivalent of £150 a month.

The speed with which Russia and its satellite countries had been opened up to the market after the Soviet collapse – dismantling the command economy before any safety nets were set up, privatising resources before any civic and democratic institutions had developed – created a huge gap between the wealthiest and the rest of the population. As the communist state disappeared, organised crime flourished, while the wider economy floundered. “Outside Riga, factories closing. It’s like dying land, that’s why people look to other countries,” Mezals said. So he contacted his old friend Valujevs, bought a Ryanair ticket and left Latvia.

The agency work he had been promised in England, cutting supermarket cabbages, was drying up. He and several other Latvian men were sitting around for days in a Fenland house, four to a room, each paying £50 a week in rent, waiting for a call. After a while, Valujevs, who was like a brother to Mezals, introduced him to another agency. A succession of precarious jobs followed – long shifts of back-breaking work in the fields or mind-numbing boredom on conveyor belts in the packhouses, sometimes paid the minimum wage, sometimes less.

Mezals started up a series of money-making ventures – shuttling luggage for people between the UK and eastern Europe, collecting old clothes door-to-door for charity, which Valujevs then sold for a profit. In other circumstances, he might have been a successful trader, playing emerging markets. Instead, the Valujevs gang, new recruits to western capitalism, used their fellow migrants for profit. Once a person was in the gang’s Wisbech housing and indebted to them, their whole lives could be commodified and put up for sale – especially if they were women.

Dace Sera was one of a number of young Latvian women who were turned into profitable commodities by the group. She came to England by bus in late 2011, with her two children, having responded to a recruitment advertisement on a Latvian website. She was placed in one of the Wisbech houses controlled by Mezals – 5 Tinker’s Drove – just a couple of minutes from the BP garage, and charged £60 a week, plus a further £40 for her children to share a room. Valujevs and Mezals kept promising her work but weeks went by without jobs materialising, so that she was soon in debt to them.

Vankova and Valujeva took her to various bank branches in Wisbech and the surrounding towns to open accounts – using fake documents as proof of address and giving Vankova’s home as the postal address for correspondence – supposedly so that Sera could claim benefits and obtain work. In fact, her identity was hijacked and converted into cash. Through January 2012, a string of subsidiary accounts were opened in Sera’s name over which she had no control. Her online banking passwords, PIN codes, and bank cards were diverted to the gang.

The pattern was repeated with other migrant workers. There would be the promise of jobs, perhaps a small loan when they arrived penniless, and an offer of help initially with bank accounts and benefit forms for those with little or no English. They described how they would quickly fall into arrears, since the jobs were irregular, then they found themselves marked down in the dreaded debt books kept by Mezals and Valujevs, and subject to threat. Strings of bank accounts were opened in their names without their knowledge.

The gang was, in fact, running elaborate financial frauds and using accounts in workers’ names to disguise the flow of stolen money. They siphoned funds off from hacked PayPal accounts and other methods of internet payment, and laundered counterfeit cheques through layers of workers’ accounts before passing the proceeds into their own accounts, or drawing them out as cash from machines around the region. The crime behind the frauds was clearly transnational and partly organised elsewhere – fraudulent cheques and payments were, for example, written out in the names of a US bank, a Scottish utility company, churches, colleges and charities in different countries, as well as dozens of innocent individuals. The Fenland gang even used their own family members to launder the money. Valujeva’s sister was severely disabled with Down’s syndrome, yet accounts set up by the group in her name were used both to hide stolen money and for multiple benefits claims, even after she had returned to Latvia. By moving the money in amounts just below each bank’s upper limit for triggering checks, they managed to avoid detection.

Behind the day-to-day racketeering, there was a menacing Russian presence. One male migrant worker described being accosted just 100 yards from his Wisbech front door as he made his way home after work one evening. He was bundled into a black car by men “like bodybuilders, behaving like mafia”, he said. They drove him to Peterborough and told him to withdraw £1,000 he didn’t know he had from a cash machine. (The machine swallowed his card.)

Sera’s identity was used in this manner for several money laundering accounts. But she, like a few other Latvian women, was used for profit in an even more sinister way. By spring 2012, Valujevs told her that her debt to the group for unpaid rent and small loans for food and nappies for her children had grown to £1,000.

She was told she had to pay it off, and given a choice: either go to India for a few days and take part in a sham marriage to enable the supposed groom to apply for UK residence, which would earn her £1,500. Or, if she was not prepared to do that, she would have to work as a prostitute. Other women said they were told they would have to sell their organs to clear their debts.

Sera was taken to London by Vankova and Valujeva to meet Valujevs and two Russian men in a big car. The Russians argued about whether her English was good enough to “carry it off”. Valujevs was supposed to accompany her to India, but at the last minute Sera was sent on her own, Valujevs having arranged for her two small children, aged five and two, to stay with a friend. The few days turned into three weeks, during which she was trapped, staying in a cockroach-infested flat, and driven around and photographed in various locations with her Indian groom and his friends. The Indian family told her they had paid £25,000 for the arrangement, but she received nothing. When she finally flew back, Valujevs told her she could no longer stay at 5 Tinker’s Drove, and that her fee had been cancelled out by her debt.

Some time later, the Russian men started calling her number. There were papers they had to get from her to conclude the deal. She did not reply at first, because she was too frightened, but it was made clear to her “if I didn’t meet them they would smash my head against the ground”. She met them with Valujevs and Mezals in the Morrisons carpark in Wisbech, and signed what they needed. Shortly after, the Indian groom applied to the British High Commission in Delhi for a UK residence visa as her spouse, but immigration authorities were suspicious of the marriage, and refused.

Santa Graudina, another young Latvian woman, who had come to England, aged 19, on the promise of a job from Valujevs, was £700 in debt to him when he told her she could pay it off by marrying an Indian man who wanted a UK visa.

Like Sera and other victims of the Valujevs group, Graudina was compromised. She had put her name to an immigration crime. She had accepted a cut of fake cheques that she was told to pay into and cash out of her bank accounts, and had been arrested (but not charged) in March 2012 for helping others open bank accounts in London with forged documents. She was more educated than the others, but she said that she had no choice but to do what she was told. She and her boyfriend said they had both been threatened by Valujevs when they argued about money owed to them.

Meanwhile, Sera, desperate for money, tried the same trick again, this time with another completely separate organiser, agreeing to have marriage photos taken with another supposed groom of Moroccan origin for a fee of just £200. Homeless, frightened for her children, and being sought by immigration officials, she eventually went to Fenland council for help, and was given a place to live.

The neighbours found the gang’s activities impossible to live with: the rows, the fights, the noise, the drinking, the rubbish and the old cars revving engines in the middle of the night. It made most of them want to keep their heads down.

One of the many houses the Valujevs gang were subletting to migrant workers was 6 Bath Road – a small nondescript postwar home in Wisbech. This was where the Tesco-carpark alcoholics were sent by Mezals, after a brief stay at 5 Tinker’s Drove. He rented out rooms there to many others too.

Police recorded more than 700 calls from Bath Road between 2010 and 2015. Mezals and Valujevs lived elsewhere, but had repeated convictions for drink-driving, with Valujevs adding to his charge sheet driving while disqualified and uninsured and obstructing police when he was stopped. Valujeva too had been convicted of drink-driving. Alcohol ran like a river through their world. Asked why drink featured so large in the lives of the eastern European community, the Lithuanian owner of the gym where Valujevs worked out said it was obvious: “Nostalgia and depression.”

Sharon Newman at 2 Bath Road told me what it felt like to have all this next door. She and her husband had done their home up immaculately. They had renamed the house “Costalot” and put up a new sign by the door. They enjoyed a good laugh.

Then the Latvians had sublet No 6. They were “all troublemakers”, she said. “There were so many people and they were always changing. They used to be drunk all the time, day and night, and we’d see them when they could hardly walk, come out and get into their cars and drive off, so we’d call the police. The worst was when there was violence towards the women. We could hear a woman one time, begging and begging it to stop, so we called the police. But she wouldn’t make a statement so there wasn’t much they could do.

“I was born here,” said Newman, “I’m 44 and I’ve lived my whole life here, and I don’t feel safe any more. They’ve ruined it.”

She used to work as a supervisor at a large food factory in Wisbech and said she had watched migrants being brought in by agencies, undermining the terms and conditions of English workers. The Newmans had been Conservative voters, but her husband Dave had joined Ukip soon after the migrants had taken over 6 Bath Road, and she joined him in putting a Ukip poster in their front window, “because we’d never seen behaviour like that before”. Dave Newman, who was by then dying of lung cancer at just 44, was driven to rage and despair by the antisocial behaviour. It disturbed his pained and fitful sleep. He complained to the council, he complained to the rental company responsible for 6 Bath Road, he complained to the police, but as far as he and his wife could see, nothing ever changed. The final insult was when Dave saw one of the men urinating in the garden while leering at their teenage daughter.

He took to writing against Polish people on a Wisbech anti-immigration blog, and then was named as a racist in a local Polish-language newspaper. His dispute was with a specific group of exploited and exploiting Latvians rather than Poles, but his real row was with the system that appeared to have no answer to a dying man’s impotent rage.

“There are nice foreigners, I’m friends with them,” Sharon Newman told me. “But it was so stressful when he was dying, we could have done without it.”

Back in Wisbech centre, three local residents in the main market square had strong views on the changes that the town had experienced. They did not feel safe going into certain areas any more – people were drunk, there were frequent fights, shoplifting, and unsolved murders. They were especially riled that to express these views put them at risk of being labelled racist.

One of them had been a land worker in the past, when there was still an Agricultural Wages Board to make sure people received a living wage and decent breaks. “I preferred being outside, so I didn’t mind it. It was head down, arses up, half-seven till half-three, and an hour break for lunch because that’s what a man could manage. Saturdays and Sundays were off.” But he reckoned it was inhuman work now.

“It’s the big farm businesses that have ruined this town, with their cheap labour,” said the older of the two men. “British workers would do those jobs, but it’s the way they pay them, the way they want them, that’s the problem.”

The woman in the group had worked in another food factory, where she had been team leader. Working patterns had switched from five days a week with overtime at weekends to rolling 12-hour shifts, four days on, four days off. “The work got harder and harder, and more and more agency people came in – foreigners. Don’t get me wrong, some of them were good hard workers, but I went home off one shift and when I came back on the next, they were still there. How can that be legal?”

After months of intelligence-gathering, Cambridgeshire police launched an operation in 2013, together with the Gangmaster Licensing Authority, and supported by the National Crime Agency. It was led by DCI Wass. In the early hours of 15 October, they entered migrant houses controlled by several gangmaster groups, and took around 80 workers to a reception centre, where they were interviewed and offered state help. Thirty-seven people were placed in the National Referral Mechanism for victims of human trafficking, including Sera and Graudina.

Valujevs, Valujeva, Vankova and Mezals were subsequently arrested and convicted, over the course of two long trials, on a number of charges. The defence team briefly argued that the operation was politically motivated, but that idea was given short shrift by the judge. Drink featured as prominently in the trial as it had done in Wisbech life. Some of the alcoholic prosecution witnesses trembled as they described what had happened to them; a key defence witness narrowly escaped being sent to the cells for contempt when he appeared in the witness box drunk in the early afternoon; Valujevs and Mezals relieved the stress of waiting for the jury to come back with their verdict in the final week of the first trial by drinking heavily. Most of those who appeared were reluctant and scared. Sera, not wanting the defendants to see her, gave her evidence from behind a screen.

Valujevs and Mezals were convicted of operating as illegal gangmasters at the first trial, held in 2014 at Blackfriars crown court in London. Valujevs, Valujeva and Vankova were convicted of immigration offences relating to sham marriages at a second trial at Huntingdon crown court in 2016. All four were convicted of conspiracy to acquire criminal property (stolen money through fraudulent bank transfers). Mezals was acquitted on the sham marriage charge at the first trial.

The English gangmaster Martyn Slender was separately convicted of using unlicensed gangmasters. He was given a 12-week suspended prison sentence and a community work order. Two other gangmaster operations had their licences revoked but were not charged. No action was taken against a third large gangmaster business called WMS – the company is run by an English family (one of the family gave evidence in court), and typically supplies around 1,000 migrant workers a day to businesses in the region – even though it had been taking workers illegally from Valujevs and Mezals.

The trials conjured up a nightmare of Fenland life, where there were no rules where you expected them to be, and when rules did exist, there was no one to enforce them.

Houses of multiple occupancy must be registered with the council, but buildings of two storeys or less do not count, however many people you pack in to them, so most of the Valujevs group’s gang houses did not fall into this category. There were also only three housing officers for the whole Fenland district council to carry out inspections at the time – the council had suffered a 37% cut in its budget since 2010.

If you charge people for transport in your vehicles, you are supposed to have a public service licence. Mezals didn’t bother about that. His cars were not registered in his name anyway, nor were many of the houses. “It just fell out of my head,” he told the court, as did income tax.

It falls to HMRC to enforce not just tax but the legal minimum wage. Many of the migrant workers had been paid less than the legal minimum for illegally extended shifts without breaks. But at the time, HMRC had just 142 national minimum wage inspectors for the whole country. According to the government’s migration advisory committee, this means that the average business, statistically, should expect a visit from an inspector once every 250 years. Unions that might have overseen conditions in fields and factories in the past are in decline. The Gangmasters Licensing Authority has lost staff, having had its budget slashed over the course of the last parliament by 20%.

A gangmaster may not by law deduct more than a fixed small amount for rent from a minimum-wage worker, but since Valujevs and Mezals were not licensed, it was not clear that this rule applied. In any case, there is no crime of charging excessive rent if that is what the market can command, as the judge at the first trial commented – adding that a significant number of members of the House of Lords had made their fortunes that way.

The Agricultural Wages Board, which set out employment terms for field workers, was abolished in 2013. The EU working time directive aims to prevent workers doing dangerously long hours, but the UK allows an opt-out, seeing it as a burden on business. The pressure on large producers to cut costs – one of the key drivers of labour exploitation – is often blamed on supermarkets squeezing their margins. A recommendation by the competition authorities in 2000 that this excessive buying power be countered by a groceries adjudicator took 13 years to be implemented. The adjudicator only acquired the power to impose penalties in 2015, and has yet to do so.

Liberalising trade rules and financial flows has enabled the free movement of goods and capital across Europe – and, with them, people. But while World Trade Organisation rules prescribe global hygiene standards in minute detail, they are largely silent on the social and labour conditions in which the goods are produced.

A complex web of small rules widely obeyed – from paying your tax to insuring your car, to giving workers proper breaks – are the threads that weave a democratic social contract and a protective state. Many people in Wisbech have become more rightwing, in protest at what they see. The collapse of totalitarian structures of state control in former-Soviet eastern Europe has combined with a shrinking of state in the west. This shrinking of the state has created the vacuum into which organised crime has rushed.

The breakthrough in unravelling the nexus of criminal gangs in Wisbech only came when officers from a wide range of enforcement bodies – the council, the fire service, the police, HMRC, the Gangmasters Licensing Authority and immigration enforcement – went out on the ground and visited properties where migrants were living. It took many hundreds of hours of police work to track the money laundering. By the year following the October 2013 operation, the area had experienced a 16% drop in crime.

Police inquiries in to other organised crime groups in the Fenland area continue. The unsolved murder inquiries remain open. One of the gangmaster companies that lost its licence has reappeared in another city, and now supplies labour to the unlicensed care sector instead.

A new murder inquiry was opened in January this year following the disappearance in September 2015 of a Lithuanian worker based in Wisbech. He had not been seen since finishing his shift on the leek harvest.

Main photograph: David Levene