Last week, a United States federal appellate court unsealed a set of documents pertaining to Lavabit, the e-mail provider of choice for former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden. The documents show that Lavabit’s founder, Ladar Levison, strongly resisted government pressure that would have resulted in the privacy of all users being compromised as a way to get at Snowden’s e-mail. Levinson went so far as to shutter the company, destroying its servers entirely.

“People using my service trusted me to safeguard their online identities and protect their information,” Levison wrote in a press release last Wednesday. “I simply could not betray that trust.”

The Lavabit case is the best known example of a company willing to go to extreme lengths in order to protect its customers’ privacy. Since Lavabit has fallen (as has Silent Circle's Silent Mail service), many journalists and business people have speculated that foreign e-mail providers might have policies that would theoretically be more resistant to government intrusion, particularly in Europe and especially in Germany and Switzerland, which have strong data protection and privacy laws.

But a closer look at German law in particular reveals that a German e-mail provider certainly wouldn't offer more protection—and would likely offer less—than a similar American e-mail provider.

In recent weeks, I’ve set up e-mail accounts at two alternative mail services, and I'm considering switching away from Gmail to one or both of these companies as my primary personal e-mail account. (Here’s my PGP key.)

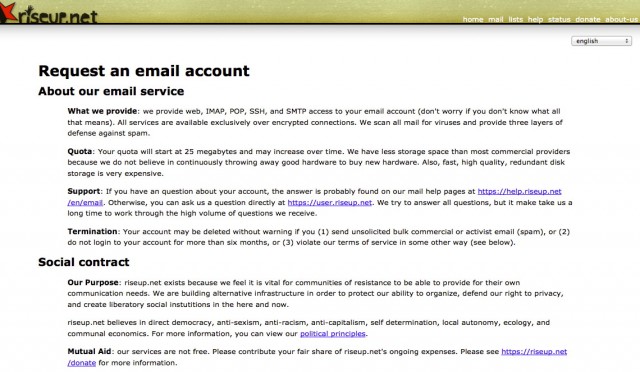

While there are many choices out there, we’re going to focus on one American service (Riseup.net) and one German service (Posteo.de) to better understand what foreign privacy policies state and what their legal requirements actually are. I chose Riseup because it's a longstanding US-based alternative for the privacy-minded and Posteo because it's a similarly marketed German alternative. Like nearly every other e-mail provider, both offer POP and IMAP support as well as a webmail interface—but they're very different in the promises that they make.

Clearly, properly encrypted e-mail offers the best security for messages both in transit and at rest. But as many Ars readers who have acted as informal tech support for their non-techy friends and family can attest, relatively few people are going to be encrypting all their e-mails by default anytime soon. So the next best thing might just be to choose an e-mail provider that will collect as little of your information as possible and will not easily turn over what other information it does have, such as IP logs or even user e-mail accounts themselves. (And yes, you can roll your own mail server or have proper hosting—but a lot people want just turnkey e-mail. Again, think about what your family members use.)

“In terms of privacy, anything is better than Google, I'd guess,” Ralf Bendrath, a senior policy advisor to a German member of the European Parliament, told Ars. “In terms of usability, of course not. Everybody has to decide for himself or herself where the priorities are, I guess.”

“Y’know, principles”

Lavabit’s own privacy policy at the time that Snowden was believed to have been using it stated that “premium users” would benefit from having their e-mail secured with “an asymmetric encryption process that guarantees that it can’t be accessed by anyone except the holder of the account password. For these accounts, only the encrypted version of the message is ever saved to disk.”

Lavabit’s policy further stated:

It is also important to know what information Lavabit does NOT store. We do not keep a record of the IP addresses used to access our services (except in the web server logs), and we do not keep a record of what information was accessed during a particular session.

In other words, Lavabit was providing a very user-friendly way to protect its customers' e-mail, even from Lavabit’s own staff, and it appeared to minimize its other data collection.

By contrast, Google says that it collects a ton of information about Gmail users:

When you use our services or view content provided by Google, we may automatically collect and store certain information in server logs. This may include:

Location information

- Details of how you used our service, such as your search queries.

- Telephony log information like your phone number, calling-party number, forwarding numbers, time and date of calls, duration of calls, SMS routing information and types of calls.

- Internet protocol address.

- Device event information such as crashes, system activity, hardware settings, browser type, browser language, the date and time of your request and referral URL.

- Cookies that may uniquely identify your browser or your Google Account.

When you use a location-enabled Google service, we may collect and process information about your actual location, like GPS signals sent by a mobile device. We may also use various technologies to determine location, such as sensor data from your device that may, for example, provide information on nearby Wi-Fi access points and cell towers.

Perhaps as a result of the recent focus on privacy policies like these, I’ve recently noticed a couple of people in my social circles switch from Gmail to Riseup as their primary e-mail provider.

“It's annoying, actually, but y'know, principles,” Jillian C. York, an activist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote to me recently when I remarked on the change noted in her e-mail signature.

“Two inboxes in Thunderbird is a pain in the ass. I'm constantly sending e-mails from one when I mean to from the other, which—when you address private mailing lists as much as I do—is a real problem.”

And will she be deleting her Gmail account?

“I probably won't,” she said. “Frankly, Gmail is a far better organizer of data than any existing tool, so I'll continue to use it for mailing lists. I am trying to shift all personal correspondence off, though (she says as she replies from Gmail...).”

“We would rather pull the plug”

Many privacy-minded e-mail users have long used Riseup, which since 1999 has described itself as a “friendly autonomous tech collective.” An archived copy of its website in 2000 notes that Riseup.net “offers permanent, free e-mail accounts to individuals and groups who are fighting the good fight against racism, sexism, environmental destruction, homophobia, corporate power, or capitalism.” The company promises:

We will never disclose your e-mail address to anyone without your permission.

We will never include advertising on our website or in your e-mail.

We will never charge for your e-mail account.

We will never go away and leave you without an e-mail account.

The entity behind the site is unknown, but the site's lawyer appears to be Devin Thierot-Orr, a law professor at Seattle University. He was listed as a contact on a press release describing a 2012 seizure of one of Riseup.net's shared servers in New York City.

He was also quoted in a 2010 story in the New York Times saying that Riseup was “started with a handful of accounts on a few donated PCs stashed in someone’s basement,” and that “ten years later, we are still volunteer-driven and have a large user base from all over the world.”

When Ars tried to contact Thierot-Orr, his voicemail said he was out on paternity leave, and he did not respond to a request for comment by e-mail.

Still, Riseup’s privacy policy clearly states that the group will take an aggressive stance: “We will actively fight any attempt to force Riseup Networks to disclose user information or logs.”

And it explicitly says that it would sooner commit a Lavabit-style shutdown than submit to government or court orders. “We will do everything in our power to protect the data of social movements and activists, short of extended incarceration,” the group wrote in an August 2013 newsletter. “We would rather pull the plug than submit to repressive surveillance by our government, or any government. We are doing everything we can, as quickly as possible, to forge forward with options that would prevent us from having to shut down, in case we are faced with making such a decision.”

So what’s the catch? Well, for one thing, Riseup only offers a pretty small amount of data storage.

Quota: Your quota will start at 25 megabytes and may increase over time. We have less storage space than most commercial providers because we do not believe in continuously throwing away good hardware to buy new hardware. Also, fast, high quality, redundant disk storage is very expensive.

When I signed up, Riseup actually gave me 92 megabytes of storage. That’s OK for now, but I’m certainly not going to be sending huge attachments with it anytime soon. Anyway, I’ve got Dropbox, WeTransfer, and other related services that I can use as backup if necessary. As Riseup reminds me: “If you increase your quota, we need you to increase your contribution!”

reader comments

121