Not all tourists count getting drunk before noon and desecrating a local monument or two as top priority for a break away, but those that do have come to represent the masses in the cities where they let loose.

Across Europe, where increasing numbers of visitors can overwhelm residents in the summer months, the backlash has started. “War” – and a new awareness campaign – has been declared in Venice. Fines for eating, drinking or sitting on historic fountains have been increased in Rome. Basilica steps where tourists congregate are being hosed down daily in Florence.

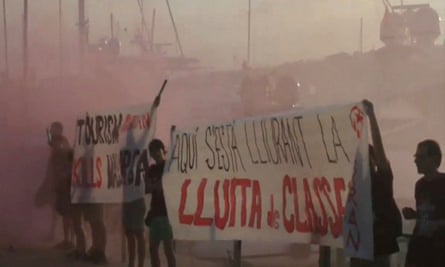

And last week, in Barcelona, vigilantes slashed the tyres of an open-top bus and spray-painted across its windscreen “El Turisme Mata Els Barris”: Catalan for “Tourism Kills Neighbourhoods.”

The message is clear: these cities are buckling under pressure. What to do about it is less obvious. In tourists and residents’ battle for supremacy of shared spaces, local authorities are uncomfortably in the middle. The tourism and travel sector is one of the largest employers in the world, with one new job created for every 30 new visitors to a destination – but at what cost to locals’ quality of life?

Xavier Font, a professor of sustainability marketing at the University of Surrey, says cities tend to ask that question when it is already too late. “You cannot wait until tourists arrive to give them a code of conduct.”

It won’t work, anyway. Attempts to influence individuals’ behaviour are futile, even counterproductive, says Font. “That attitude of ‘what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas’ doesn’t just apply to Vegas anymore. When we go on holiday, we’re selfish.”

As a consultant for national tourism boards, industry associations and businesses, Font asks not how do we change tourists’ behaviour, but how do we change tourism so as to manage its impact. If it is to be made better, more sustainable, less of a burden on cities and the people who live in them year-round, the work should have begun well before visitors have bought their tickets.

The World Economic Forum recorded 1.2 billion international arrivals last year – 46 million more than in 2015, and increases are predicted for the coming decade, prompting the UN to designate 2017 the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development. More people are travelling than ever before, and lower barriers to entry and falling costs means they are doing so for shorter periods.

The rise of “city breaks” – 48-hour bursts of foreign cultures, easier on the pocket and annual leave balance – has increased tourist numbers, but not their geographic spread. The same attractions have been used to market cities such as Paris, Barcelona and Venice for decades, and visitors use the same infrastructure as residents to reach them. “Too many people do the same thing at the exact same time,” says Font. “For locals, the city no longer belongs to them.”

Compounding the problem is Airbnb, which, like credit cards and mobile roaming, has made tourists more casual in their approach to international travel, but added to residents’ headaches. Landlords stand to earn more from renting their properties to tourists than they do to permanent tenants. Those who share their apartment blocks with Airbnb hosts have been incredulous, says Font: “‘No longer do we have to share the streets with tourists, we have to share our own buildings?’ We get residents saying, ‘I don’t want my neighbourhood to become like the city centre.’”

#EnjoyRespectVenezia | https://t.co/ojCXlEPEP1 @veneziaunica @visitmuve_it @muoversivenezia @DetourismVenice @aGuestinVenice @TurismoVeneto pic.twitter.com/x36Bdwqr4t

— Comune di Venezia (@comunevenezia) July 29, 2017

In Barcelona, Font’s home city, the council has Airbnb in the sights of its crackdown on unlicensed holiday rentals, and doubled its team of inspectors to 40 in June. Over the 25 years since it hosted the 1992 Olympic Games, the city has experienced steady growth in tourist numbers, to an estimated annual total of 30 million. Its cruise port is the busiest in Europe; its airport, the second-fastest growing.

Consequentially, it has become the poster city for how a place can “groan under the weight of its popularity”, as Font puts it. He was commissioned by the city of Barcelona to explore how it might best promote sustainable development, and his findings – published in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism in April – have been incorporated in part into its 2020 strategic plan.

It shows that Barcelona has moved past the point of simply complaining about its troubles with tourists, says Font, and is “starting to do something about it”. One course of action is widening what the city calls the “tourism spectrum ... to diversify the image and practices of visitors to the city”.

Currently, tourists’ “intensity and volume” is very unequally dispersed; it is hoped that a greater range of them, with different motives, priorities and interests, will ease the congestion around the main attractions.

This starts with marketing, says Font, who notes that Amsterdam has started advising visitors to seek accommodation outside of the city centre on its official website. “That takes some balls, really, to do that. But only so many people will look at the website, and it means they can say to their residents they’re doing all they can [to ease congestion].”

Another beleaguered city, Venice, has employed a similar strategy as part of #EnjoyRespectVenezia, a new campaign launched last month following a protest against the tourism industry by 2,000 residents. Translated into 10 languages, it publicises fines of up to €500 for picnicking in public, swimming in canals, even lingering too long on bridges.

But it also proposes a better way it is calling “detourism”: sustainable travel tips and alternative itineraries for exploring an authentic Venice, off the paths beaten by the 28 million visitors who flock there each year.

A greater variety of guidance for prospective visitors – ideas for what to do in off-peak seasons, for example, or outside of the city centre – can have the effect of diverting them from already saturated landmarks, or discouraging short breaks away in the first place. Longer stays ease the pressure, says Font. “If you go to Paris for two days, you’re going to go to the Eiffel Tower. If you go for two weeks, you’re not going to go to the Eiffel tower 14 times.”

Similarly, repeat visitors have a better sense of the culture. “We should be asking how do we get tourists to come back, not how to get them to come for the first time. If they’re coming for the fifth time, it is much easier to integrate their behaviour with ours.”

Local governments can foster this sustainable activity by giving preference to responsible operators, and even high-paying consumers. Font says cities could stand to be more selective about the tourists they try to attract when the current metric for marketing success is how many there are, and how far they’ve come. “You’re thinking, ‘yeah, but at what cost …’”

He points to unpublished data from the Barcelona Tourist Board that prioritises Japanese tourists for spending an average of €40 more per day than French tourists – a comparison that fails to take into account their bigger carbon footprint. French tourists are also more likely to be repeat visitors that come at off-peak times, buy local produce, and spread out to less crowded parts of the city – all productive steps towards more sustainable tourism, and more peaceful relations with residents.

But part of the path forward is factoring in tourists as a part of urban life, and even embracing them – a hard ask at a time when they are in many places public enemy number one. When it comes to instigating the necessary cultural shift, authorities’ abilities are limited.

Catalan authorities once ran a television ad campaign encouraging locals to tolerate tourists, says Font, paraphrasing its takeaway message as: “Even if you don’t like them a lot, they come here to spend money.” But it had diminishing returns over time as residents decided that it was not their responsibility to welcome the group doing such damage to their quality of life.

Underpinning Barcelona’s new strategy to 2020 is the understanding that tourism is “an inherent and constituent part” of the city, not an alien phenomenon: “Tourists do not have to be considered passive players … but rather as visitors with rights and duties.”

Everyone has a part to play in facilitating that change of perspective, says Font: tourists, cities, residents and operators. But everyone stands to benefit, too.

As a boy in Barcelona, he would observe belligerent visitors overwhelm his city, drinking at inappropriate times of day, dressed in sombreros. When they made an effort to speak Spanish and try local cuisine (“rather than asking for bangers and mash”), he recalls locals being more receptive.

“When tourists dress differently to us, eat differently, and are active at different times of the day,” he says, “we resent them much, much more.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion