Backup child care, attendance confusion: Low-income families and the LA teachers strike

LOS ANGELES – Matthew Robles spun in a circle holding a sign, then stopped abruptly and turned to his mom.

“Did you say my grandma’s gonna babysit me?” he squealed. Zonia Robles nodded. “Cool!” he cried.

On Day Two of the teacher strike in Los Angeles, which is impacting more than half a million kids as 34,000 teachers stay off the job, Zonia Robles decided again to keep Matthew, 6, out of school. That meant he helped her support teachers on the picket line and then joined her at work, where she is a legal assistant. Later in the week, she planned for her mom to watch him (much to his delight).

But if the strike stretches into next week, she could be in a bind. The teachers union has offered to resume bargaining on Thursday, although the strike will continue. It's their first bargaining session since talks collapsed last week.

Her plight is familiar in Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, which serves primarily low-income families. Eighty percent of its students receive free or reduced-price lunch.

These are the children who rely on schools the most. And this week, their teachers are gone, and their schools barely have the staff to operate.

More:My daughter's teacher is on strike. As a mom, I stand on the picket line with her.

More:What you need to know about the LA teachers strike

It's complicated: Grandparents take a bus to pick up a child

Los Angeles' children count on schools for meals, shelter and supervision – much less helping them stay on track academically.

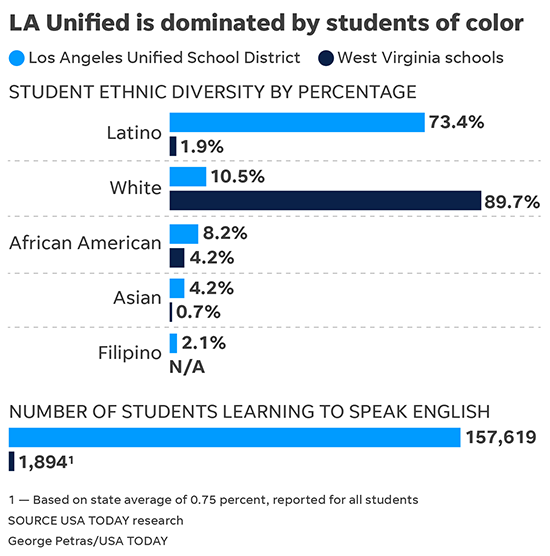

Unlike in West Virginia, whose teacher strike in February kickstarted a year of walkouts across the country, many LA students need school to help them communicate. More than 150,000 students in LAUSD are still learning to speak English.

Most of those kids come from working households, and their families don’t have the resources to hire last-minute child care. In many cases, extended relatives pitch in.

Zonia and Matthew Robles live in another neighborhood – near a school Zonia said she was “not comfortable” sending Matthew to – but commute to his kindergarten class at Tom Bradley Global Awareness Magnet Elementary School in south Los Angeles.

Because Zonia works full-time, one of her parents rides public transit each day to pick up Matthew. Then they board the city busy together and head home. It’s a time-consuming process.

Tom Bradley Elementary, a school in a historically black neighborhood, gets extra federal money because of the high percentage of low-income children. The Robles family is not the only one trying to juggle child care and the strike.

Yet this week some students are staying out of school completely, because their parents support teachers or don't feel comfortable with the supervision at school – or simply because the district is being lenient with attendance.

'Did you eat dinner last night?'

The district reported that only 144,000 students were in school Monday, including students who attend independent charters where teachers weren't striking, compared with LAUSD’s total enrollment of nearly 700,000. The attendance got a little better on Tuesday, but declined on Wednesday.

Low attendance figures mean few students getting breakfast or lunch at school. On a normal week, some students even receive a dinner to take home.

“For a lot of our students, these are their only guaranteed meals,” said fifth-grade teacher Dana Sapper, of Cohasset Street Elementary in Van Nuys. When a child in her classroom complains of a headache or tummy ache, her first question is always: “Did you eat dinner last night?” Often, the answer is no.

At a meeting in December, United Teachers Los Angeles – the union behind the strike – announced a grant program available if the teachers walked out. The union would provide up to $300 per school to buy groceries, which teachers could distribute on the picket line to any child. Sapper applied immediately. Donations from parents at other LA schools have also gone toward food for children.

“Quiero banana!” A boy passed the table stacked with food on Wednesday, gesturing to his mother.

"Do you want a banana?" Sapper handed him and his sister brown paper bags, and they loaded them up with crackers, fruit, Lunchables, string cheese, juice boxes and more. They waved goodbye, comparing treasures as they walked away.

Schools: Havens of stability?

There's a general consensus among education researchers that instability is bad for kids. Repeated disruptions make it harder for students to progress academically.

Low-income students are more likely than their wealthier peers to confront multiple forms of instability, such as changing residences, changing schools, experiencing a parent's job gains and losses or even watching staff turnover in their classrooms.

"What I see a lot of is just chaos or derailment," said Stefanie DeLuca, a sociologist at Johns Hopkins University, who researches how social forces and school experiences affect the life outcomes of disadvantaged students.

"If school instability is happening within the context of a lot of other life instability, then that's all going to make it harder for kids to learn."

The strike may compound all that.

More:Los Angeles teachers' strike: How one middle school is being creative to cope

For some families, confusion about the strike

There’s general confusion among low-income families about what’s going on this week.

Because many parents work multiple jobs, they don’t have time to scour the Internet to figure out alternatives for kids who aren’t in school. (Many community rec centers are open extended hours.) Parents also report varying directions from the district regarding mandatory attendance. The language and cultural barriers for some parents don't help, either.

Sharie Mason, whose son Kemaja Francis is in third grade at Bradley, pulled up to the curb around 7:30 a.m. Tuesday and bid him goodbye.

When a reporter asked if she thought about holding him out of school, Mason said she was under the impression she had no choice – that kids had to be in class. She said she got a letter from the district last week: If Kemaja missed five consecutive days of school, she would be ordered to attend a court hearing and possibly pay a $1,000 fine, which she could not afford. A striking teacher shook her head and said, "It's parent choice."

California schools depend on daily attendance figures to get money from the state, and the district is losing millions of dollars each day of the strike. Superintendent Austin Beutner has declined to say how long the district could sustain those losses.

Teachers hope to use the net losses to pressure the district to dip into its savings account to pay for more nurses, counselors and libraries. The district says that money is promised to other areas and spending too much of it would bankrupt the school.

“Low-income families know we’re fighting for them,” said Ly Hua, a 15-year LAUSD veteran currently teaching at Bravo Medical Magnet. “They are the ones who need nurses and counselors the most.”

Traumatized students should have an extra social worker, teachers say

At Florence Griffith Joyner Elementary School in the Watts section of Los Angeles, many parents said they had kept their kids out of school Monday, but were bringing them back. They had to go to work.

“I don’t even want to send them to school,” said Chrystal Ferguson, a single mom to three. “The kids are not learning.”

But it’s not an easy choice for her. She works as both a security guard and in-home caregiver to provide for her family. Still, she planned to pull the students if the academic situation did not improve.

Because the area is low-income – the school is next to a housing project – striking teachers say they want the district to add not only a full-time nurse at the school, but another psychological social worker as well.

Lezeth Robles, who is the social worker there now, said children were traumatized by having witnessed a shooting near the campus and required counseling.

"Some of the children saw the body twitching," Robles said.

Contributing: Erin Richards