A tool developed by researchers at Southampton University has indexed historic maps, photos and historic documents to provide a simple location search tool for the UK.

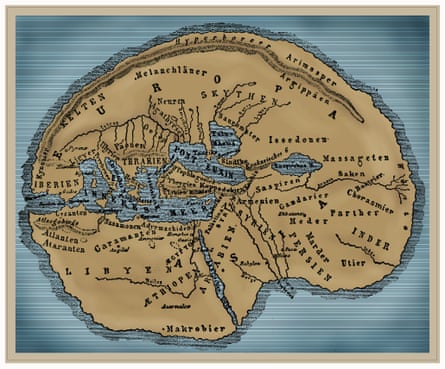

The Pelagios 3 project takes data from ancient Latin and Greek sources, which formed the basis of two previous Pelagios projects, and builds on it with documents and maps from Arabic sources, medieval European and Chinese maps, and seafaring charts from the 13th century, cross-linking them into one searchable database.

A partnership

The project is led by archaeologist Dr Leif Isaksen working in partnership with the Open University and the Austrian Institute of Technology, and funded by the Andrew W Mellon Foundation.

The tool is open to the public and researchers. A search for a UK town, city or village returns information up to 1492 matching names in text documents from the period as well as maps and images, connecting facts, stories and maps of places they wouldn’t ordinarily be able to find, or that would be separated in disparate documents and archives.

The index also includes local descriptions and stories from the time, including how residents talked about locations at different times and how they related to other places.

More than just locations

“Places mean much more than dots on a map,” says Dr Elton Barker, co-director of Pelagios and a reader in ancient Greek literature and culture at the Open University. “We are used to seeing the world mapped out in a particular way, a partial ‘truth’ that is only exacerbated by modern technologies, such as Google Earth.”

“For instance, it’s remarkable to see that Claudius Ptolemy, a Roman astronomer, used London as one of his primary reference points for global time zones in the late second century, just as we do today,” said Isaksen.

Combining documents from different cultures, languages and sources across time allows cross-referencing, corroboration of evidence and allows the reader to build a much broader, richer picture of both well-known cities and more obscure places.

Isaksen and his team are bringing the open, interconnected-data approach, which has enabled significant research advances in subjects ranging from systems biology to Google’s flu trends, which charts the spread of influenza outbreaks across the globe, to the world of ancient history.

"With such an unprecedented variety of data linked together, it will be possible to trace in broad terms the continuities - and discontinuities - of people's responses to the world around them," Isaksen told the Guardian. "Equally exciting is that if you're interested in a particular place, you'll be able to bring together disparate fragments of its life history, its connections with other places, its stories and imagery.”

Citizen science

The simple search box that currently represents the front end to the Pelagios project is just the start. Isaksen and his team hope to get the general public involved in the evolution of both the data set and its tools.

As the research team discover unknown places and texts without obvious geographic links they will be put onto the project’s site, for interested parties to access.

The aim is to integrate some 'citizen science', allowing members of the public to contribute to the project to help identify unknown places and texts.

Isaksen is also actively looking for input on where the project’s tools should go next, and how best to evolve the database’s interface to help both researchers and amateur historians.

“The Pelagios project would be a useful starting point to any classics research project, as the more information that’s available when starting out the better," said Matthew Hosty of Jesus College, Oxford, who is conducting research into ancient parody.

"I’m all for unexpected connections like this, especially as many researchers become so specialised that it’s difficult to make links to other disciplines or languages”.