The Surprising News From One Small Town About Immigration Reform

In a place as unlike Miami, New York, or L.A. as you can imagine, America's unsettled immigration policy has a profound effect.

When I was thinking like a DC policy person, what was the biggest surprise from the time my wife and I spent in Holland? It involved immigration, in a way I would not have expected from what is now our favorite lake side, Dutch-themed, manufacturing-intensive, brewery-and-university-rich small Michigan town.

When I was thinking like a DC policy person, what was the biggest surprise from the time my wife and I spent in Holland? It involved immigration, in a way I would not have expected from what is now our favorite lake side, Dutch-themed, manufacturing-intensive, brewery-and-university-rich small Michigan town.(Today's photo theme includes windmills in Holland, precisely because I've tried to establish by now that so much else is going on in what some visitors experience as a kitschy "Tulip Time" resort. This is the windmill outside Russ's Restaurant, whose main sign is shown lower down.)

During the time we were in Holland, just before the Syrian blow-up, the big political story out of DC was how the Republican party would position itself for or against an immigration-reform bill. Would the Rubio "soft" line prevail, or would he have to backtrack from anything that seemed like amnesty, and so on.

I was not expecting to hear much about that in Holland. Instead: tax rates, environmental or trade policy, Obamacare, et cetera. But in fact it came up surprisingly often, and most dramatically from a man I mentioned yesterday, Brian Davis, the local superintendent of schools.

The previous post described the main challenge Holland's public schools had been dealing with: white families and students moving across town borders to the suburban districts, or to religious and charter schools in town, the steady arrival of mainly non-white immigrants and migrant workers, and the emergence by 2005 of a mainly non-white public school population in a mainly white small town.

This shift mattered because of the nature of Michigan's school funding, which works differently from most other states. In most of the country, each district mainly funds its own schools. Rich districts do better -- including when rich, childless families are still paying for the local schools. Poor districts do worse. Michigan's, by contrast (and as best I understand it) is much more centrally funded. Districts send their money into the state. The state sends money back to the schools, based on how many students they enroll. Thus a migration of kids to private or religious schools, which reduces the public-school headcount, undercuts public school funding more directly than in most other places.

The Holland public schools, which had been in trouble for a while, coped with this problem by getting a big local-bond measure passed three years ago, by a comfortable margin, even though a large majority of city residents had no kids in the public schools. Brian Davis (left, in a Holland Sentinel picture) talked to me at some length about how that happened, and what it said (in a good way) about the town, and why it mattered in a larger civic sense. "Had that bond measure not passed, I really believe it would have contributed to the slow death of the institution of public education as we know it today," he said. "We could have evolved into a district that served largely at-risk kids. There is nothing wrong with that, but it further segregates out resources and opportunities."

"We have children who come from homes with a million-plus annual income, and ones who come from homes with incomes under $20,000," he said. "Just under 10 percent of them are considered homeless. When you factor all those variables in, it’s the future of what public education looks like." Like every school representative we've talked with in the Midwest, he began reeling off some of the 20 native languages of his students. "Of course Spanish, but then Japanese, Russian, Tagalog, Korean -- we've got more Garcias than Vans."

"We have children who come from homes with a million-plus annual income, and ones who come from homes with incomes under $20,000," he said. "Just under 10 percent of them are considered homeless. When you factor all those variables in, it’s the future of what public education looks like." Like every school representative we've talked with in the Midwest, he began reeling off some of the 20 native languages of his students. "Of course Spanish, but then Japanese, Russian, Tagalog, Korean -- we've got more Garcias than Vans."But to me the real news was his stress on the disruptive effect on students of prospective deportations. As he put it:

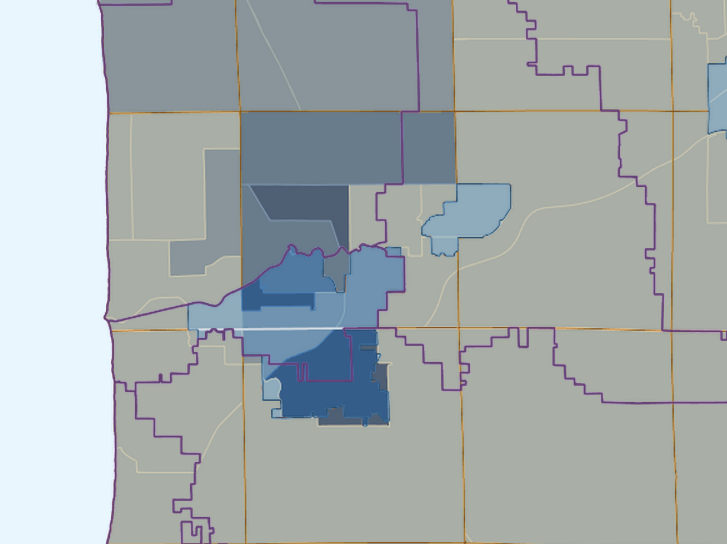

"The other big factor is the proportion of students and families who are undocumented." He said that -- by definition -- he didn't have a precise number, but "From talking with adults or asking students about their friends, the number is higher than anyone might expect. It could easily be 30 percent or greater." [Map, from yesterday's post, of Hispanic share of population in Holland and the surroundings.]

Then he said, "The sad part is that we don't usually find out until it's time for students to apply to college. And then the students say, 'You know, I'm not really as interested as I used to be.' They have to fill out papers to be eligible for scholarships -- and unless you have the financial means to go to college without help, which most families don't regardless of ethnic background, that's the end of it."

Then he said, "The sad part is that we don't usually find out until it's time for students to apply to college. And then the students say, 'You know, I'm not really as interested as I used to be.' They have to fill out papers to be eligible for scholarships -- and unless you have the financial means to go to college without help, which most families don't regardless of ethnic background, that's the end of it.""Say I have an older brother, who has just finished high school, and he finds out he can't go to college," Davis said. "What incentive is there for me to do well in school?" This is all the more so, he said, when the mother or father in the family is deported. ("Those numbers are going down, but even one is too many.")

Davis had lots more to say, as did industrialists in the area, about the ways they were trying to give high school students experiences and connections with local companies, so the ones who didn't go to college could find jobs. We'll go into that another time -- plus a program a local private college has set up to let kids of undocumented/illegal parents still get loans and aid.

Davis had lots more to say, as did industrialists in the area, about the ways they were trying to give high school students experiences and connections with local companies, so the ones who didn't go to college could find jobs. We'll go into that another time -- plus a program a local private college has set up to let kids of undocumented/illegal parents still get loans and aid.Here is the point for now: in a very strongly conservative-Republican congressional district, in a tiny (and successful, and conservatively religious) town as far removed from standard immigration stories as any you will find, a central concern in school performance was not simply the obvious challenge of handling America's ever-diversifying population. Instead it included the ripple effects on children who have grown up here in a legal twilight zone. This is the kind of thing that is happening on a local level while political parties figure out how to "position" themselves.

Below, a Holland Public Schools photo from last year's high school graduating class. And the one above is from the very nice Holland Museum.